Letter from the Editors #7

In this issue of Georgian Folklore, authors share stories preserved in memory — in the forgotten chronicles of history and in mythical-ritual practices.

Here you will find tales of illnesses once considered divine, of musical instruments that had almost vanished but have been brought back to life, of families who safeguarded ancestral traditions through times of upheaval, and of individuals who share their journeys in the footsteps of their forebears.

We begin with an introduction to the mythopoetic world of childhood infectious diseases, known as the batonebi (lords). Maia Gelashvili explores this complex phenomenon from multiple angles, showing how these incorporeal beings — who are said to descend from the White Sea — are not merely bringers of illness but agents of cosmic forces and guardians of moral order.

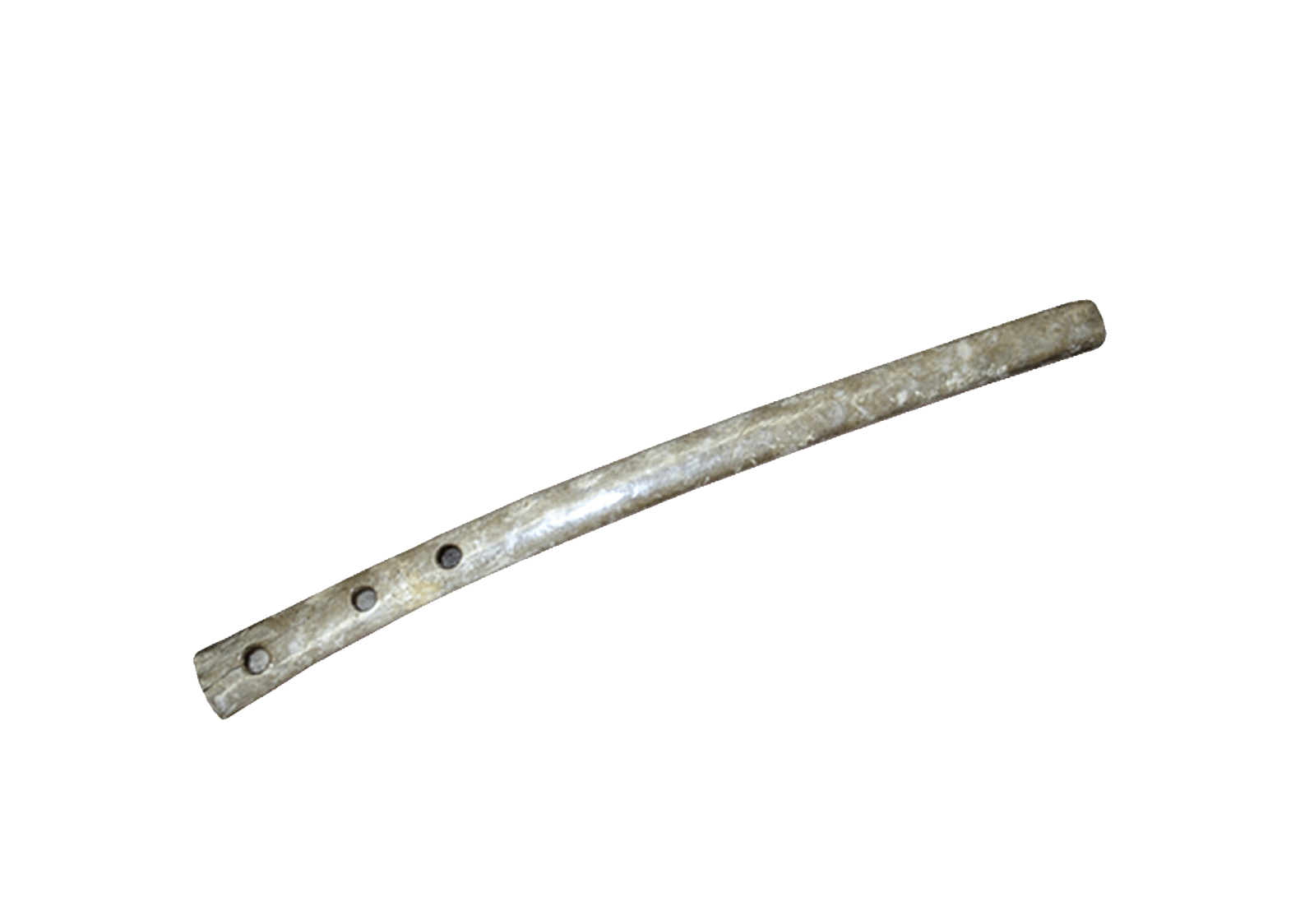

In a completely different, non-mythological context, Tevdore Gogoladze helps us rediscover the ueno salamuri, a reedless flute whose voice once echoed across Georgian pastures but was nearly lost during the Soviet era. The author raises the concern that, despite current efforts, the ueno salamuri may ultimately disappear — and asks whether such an ancient instrument should remain confined to a museum display or be returned to breath and hands.

Two articles in this issue are devoted to the legacy of families who have preserved the living tradition of Georgian singing across generations. Besarion Makhatadze writes about the musical heritage of the Kandelaki family in Imereti — particularly Ivane, Okropiri, and Sino — whose voices once filled cathedrals and palaces. His article highlights the family’s vital role in sustaining and developing the liturgical singing tradition of western Georgia.

Luarsab Togonidze’s photo-essay turns to eastern Georgia, reminding us of the Karbelashvili family, distinguished guardians of the region’s chanting school. In the 19th century, as Imperial Russia sought to suppress the Georgian Autocephalous Church, the Karbelashvilis played an important role in protecting sacred music from erasure.

Sandro Natadze’s article recounts his long journey to recover the life and creative legacy of Tamar Mamaladze, Georgia’s first female ethnomusicologist. This is not only a story of the author’s perseverance — driven by a tireless passion for research — but also an act of revival: it honours Mamaladze’s legacy, reanimates the voices she recorded, and brings forgotten songs back into the living memory of tradition.

Finally, in her extensive essay, Eter Intskirveli takes us back to a pivotal moment in Georgia’s more recent history — the 1937 ‘Decade of Georgian Art’ held in Moscow. Behind the bright surface of this state-organised showcase lay scenes of repression, manipulation, and fear. The article traces the tragic destinies of historical figures caught up in the moral decay of the totalitarian regime. It reveals how even the system’s most loyal servants could become its victims, and how the theatre, instead of being a space for cultural expression, became a place shadowed by existential threat.

Altogether, the articles in this issue open pages from the history of Georgian folk culture and remind us that traditions do not preserve themselves. Safeguarding cultural heritage demands research, effort, understanding, dedication, and love.

The Editorial Team

.jpg)

.jpg)