Ueno Salamuri (Reedless Flute) — a living tradition or a museum exhibit?

Discovering the Ueno Salamuri (Reedless Flute)

It could be said that my interest in the ueno salamuri was no accident. From childhood, I was a member of an instrumental ensemble and played the salamuri for many years, so I always paid close attention to Georgian folk instruments.

I first heard the sound of the ueno salamuri in my early years, through the melodies performed by the musician and instrumentalist Aleko Khizanishvili, whose music left an indelible mark on my childhood imagination. At the time, I viewed the ueno salamuri as an archaic instrument from the past, capable of playing only a handful of simple melodies. However, this perception changed dramatically when I encountered recordings of ueno salamuri melodies on audio albums[1] published by the Tbilisi State Conservatoire (Ethnographic Sketches – Salamuri documentary series).

At the same time, the discovery of ethnophore Zaur Tetrashvili — a living performer of the ueno salamuri — in the village of Shilda in 2020 by folklorist Beka Bidzinashvili, finally convinced me that this was not a mere museum relic, but a still-living instrument. Once an integral part of pastoral life, especially among shepherd communities, the ueno salamuri has survived into the present day.

Ueno Salamuri — An Element of the Shepherd’s Life

The ueno salamuri was more than just a musical instrument for shepherds — it also served practical purposes. Most notably, it was used in animal training: shepherds guided their herds or flocks using specific melodies. Different stages of grazing had their own distinct tunes, which acted as signals for the animals.

At the same time, the music had a meditative effect on the player, fostering a sense of unity and inner calm. Shepherds played the ueno salamuri daily — not only as a means of emotional expression, but also to continually refine their technique and expand their repertoire.

Shepherd with His Flock — painting by Niko Pirosmani © National Library of Georgia

As a result, the art of playing the ueno salamuri has reached a high level of refinement. As a form of living cultural heritage, it also holds significant potential for further development.

Challenges of the 20th Century

In the 1930s, collectivism as a mode of thinking, along with the dominant monumental style of Soviet art, had a significant impact on the forms of folk performance, including those involving musical instruments. Georgian folk instrument orchestras emerged as a product of this era.

Soviet ideology introduced a new cultural order: Georgian folk instruments — which had traditionally existed independently and were not associated with ensemble performance — were now reorganised into European-style orchestras. Traditional Georgian instruments were adapted to the European tempered tuning system, and new European rules of harmonisation were imposed. Georgian folk melodies also began to be transcribed using the European system of musical notation, which confined them within formal structures and restricted their improvisational freedom.[2]

Giorgi Changashvili. Zemo Khodasheni © LEPL Ilia Chavchavadze National Library of Georgia

However, the ueno salamuri failed to integrate into the orchestral format. There were several reasons for this. On the one hand, playing this type of salamuri required a specialised technique, which made ensemble performance difficult. On the other hand, the reed (eniani) salamuri, with its broader musical range and more powerful sound, gradually became the dominant instrument. As a result, the ueno salamuri, which had sounded natural in traditional contexts, failed to find a place in orchestral arrangements and gradually disappeared from the folk scene.

In addition, many melodies that once served practical purposes in everyday life were removed from the stage repertoire. Over time, important musical examples such as meghoruli (for pigs), samgzavro (for travel), satirali (for lamentation), makruli (for wedding escort), and various types of shepherds’ melodies were forgotten.[3] Furthermore, the ueno salamuri gradually disappeared not only from the stage but also from daily life. In the second half of the last century, the tradition of playing it was primarily preserved by the older generation, and it became increasingly unfamiliar to the young. Entire generations grew up remembering how their uncle, father, grandfather, or neighbour had played the instrument, yet they neither knew how to play it themselves nor understood the techniques involved in its manufacture.

How and in what form has the heritage of the ueno salamuri been preserved?

In the last century, accounts of the ueno salamuri were mainly recorded in printed sources — newspapers and scholarly publications — as well as in photographs and audio-visual recordings. Of particular importance were the field expeditions conducted by folklorists such as Otar Chijavadze, Grigol Chkhikvadze, Kakhi Rosebashvili, and others. They sought to collect oral histories about the ueno salamuri and its production process, transcribe tunes into notation, and record them on audio tapes.

The Ueno Salamuri as a Subject of Scholarly Research

Ivane Javakhishvili was among the first to pay special attention to Georgian instruments, including the ueno salamuri. Unsatisfied with the limited written sources, the scholar relied on the study and comparison of oral accounts from contemporary tradition-bearers to establish the golden rule of proportions for the traditional ueno salamuri: one tsida[4] at the top, one tsida in the middle (where the finger holes are evenly spaced), and a length of three to four fingers at the bottom. Georgian terms for producing low and high register tones on the ueno salamuri are also recorded: playing on the stvini and playing on the dvrini (also called bokhi, meaning low or bass sound).[5]

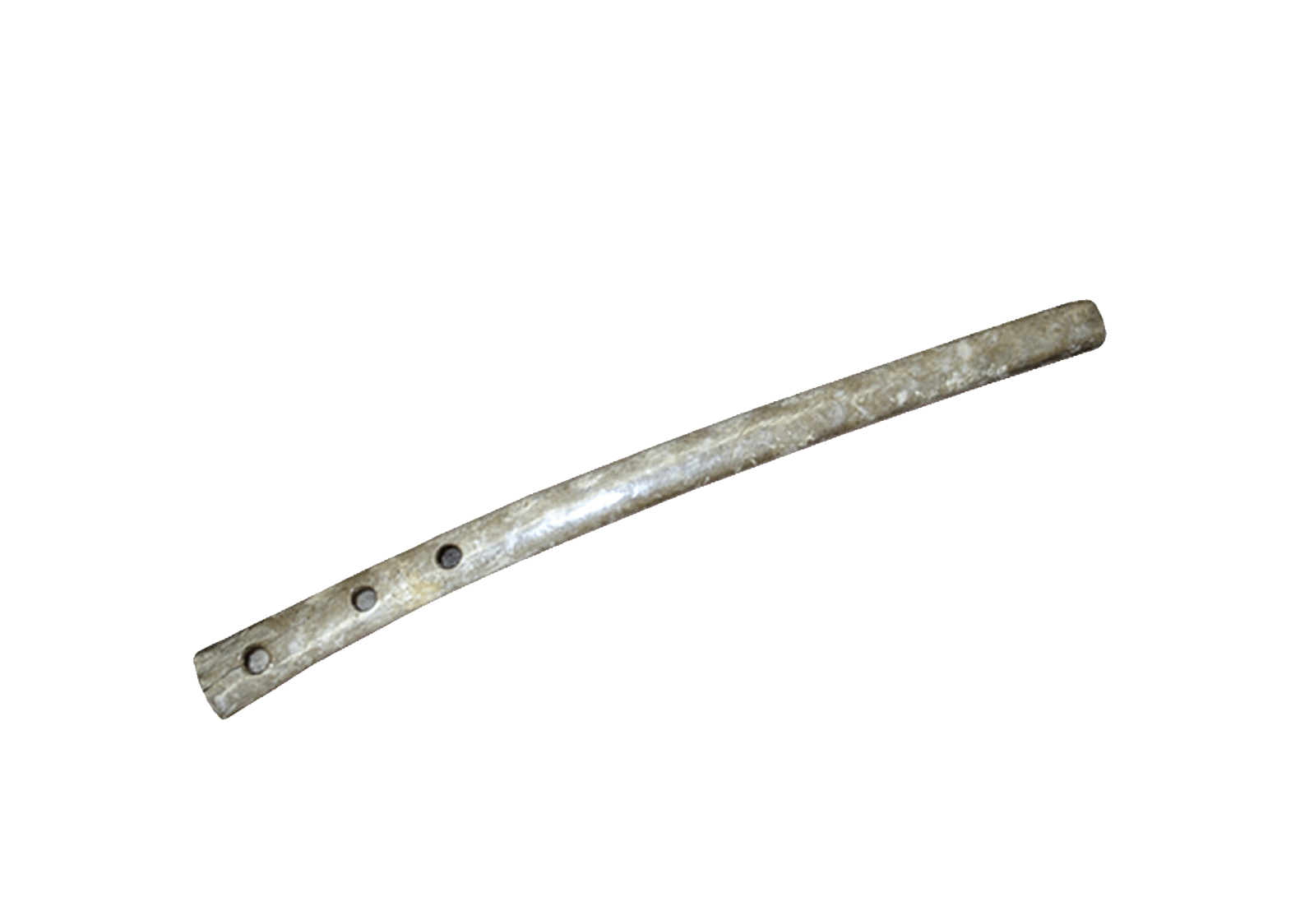

Traditional proportions of the ueno salamuri: 1 tsida + 1 tsida + 4 finger placements

The composer and founder of Georgian musical folklore, Dimitri Arakishvili, devoted particular attention to folk instruments and conducted studies on both Georgian and non-Georgian types of ueno salamuri, describing their dimensions and, in some cases, their tuning systems. Notably, he observed that when measuring the length of the ueno salamuri, the third finger — rather than the index finger — was used to define the unit known as tsida.[6]

A letter by Viktor Belyaev is dedicated to the comparison of two ueno salamuris: one measured by Belyaev in 1930, which belonged to Alexandre Oganezashvili, and another preserved in the Museum of Georgia. His findings confirm the so-called “golden rule” of ueno salamuri proportions.[7]

In his distinctive study, Kakhi Rosebashvili compiles earlier research on folk instruments and proposes a method for reconstructing the dimensions of the ueno salamuri, as performed by a specific musician, using mathematical formulas derived from transcribed melodies.[8]

Folklorist Grigol Chkhikvadze, in his unpublished work Georgian Musical Folklore, summarises the materials he collected on the ueno salamuri, outlining its construction, structure, performance techniques, and associated melodies.[9]

The work of Manana Shilakadze is also of great value in the study of the ueno salamuri, offering a synthesis of previous scholarship. Her research focuses on the instrument’s method of construction and the determination of its tonal structure.[10]

Festival Life and Technological Progress

Events held during the Soviet period, such as the Festival of Amateur Ensembles, also played a role in preserving the heritage of the ueno salamuri. Renowned salamuri players such as Piruz Aliashvili, Ivane Raibuli, Shalva Mirianashvili, and others performed actively at these festivals. Thanks to such occasions, audio recordings of the ueno salamuri, photographs of performers, and the melodies they played have been preserved.

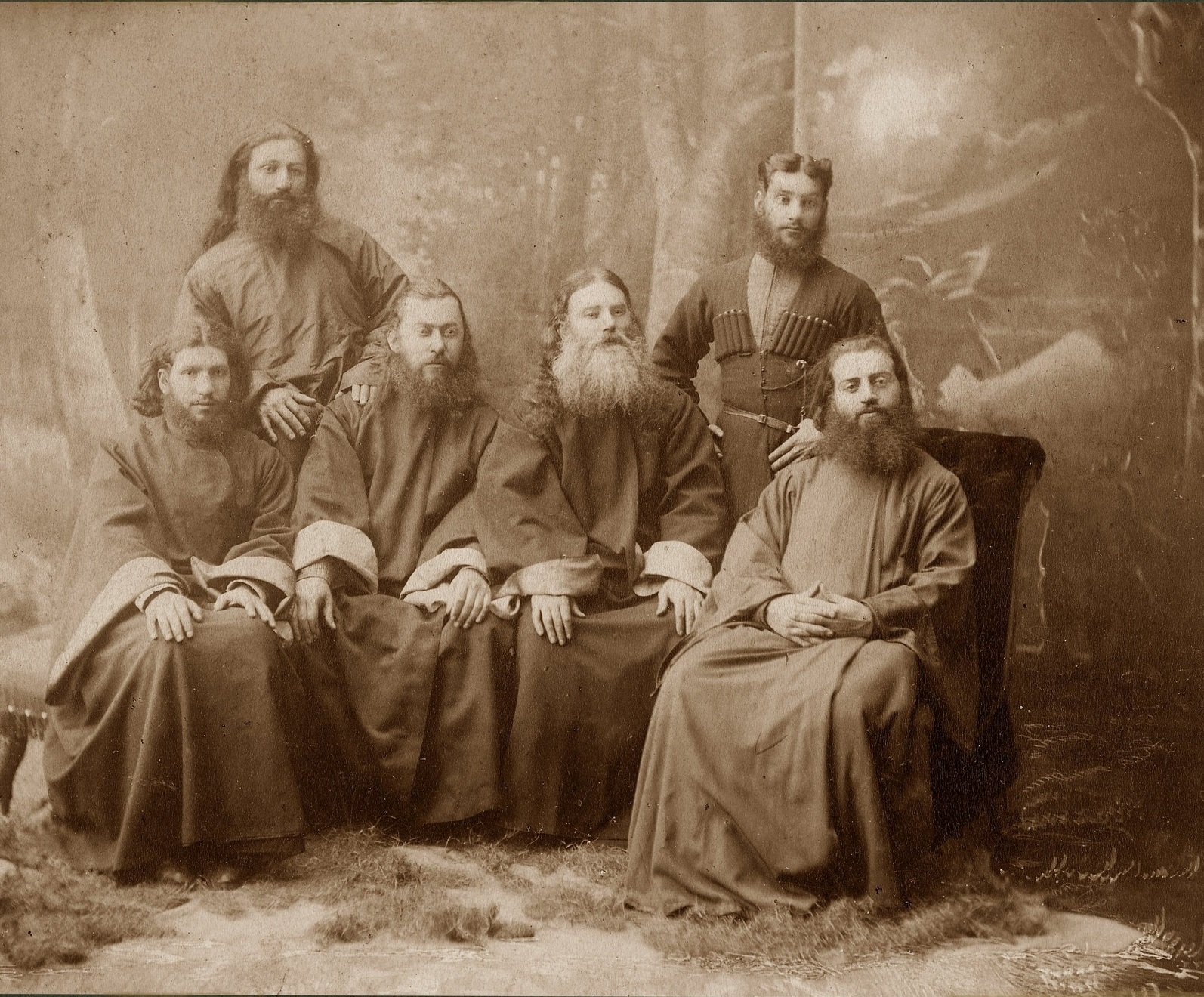

Participants of the Republican Competition of Independent Artists at the Shilda Culture House: Levan and Shakro Mirianashvili perform a wrestling tune on the ueno salamuri, 1959 © National Archive of Georgia.

Technological progress has had a significant impact on the study and preservation of folk heritage. While in the last century folkloric material was preserved mainly through printed publications and audio or video cassettes, today the digitisation and systematic archiving of such materials has become a reality. This not only helps safeguard information but also greatly improves accessibility for anyone wishing to study or explore folklore.

In this regard, the digital catalogue of folkloric materials plays an invaluable role, enabling me to observe the overall picture that has developed around the ueno salamuri over time. The material gathered so far allows us to assess the legacy of this ancient instrument and its place within the broader tradition of folklore.

The following audio recordings of the ueno salamuri and related instruments are currently preserved in these archives:

Tbilisi State Conservatoire Archive / National Archives of Georgia:

Piruz Aliashvili, Akhmeta district, 1958 – 14 melodies;

Abria Sidonashvili, Telavi district, village Ikalto, 1964 – 5 melodies, plus an account about the ueno salamuri;

Ioseb Mangoshvili, Kvareli district, 1959 – an account about the making of the ueno salamuri;

Shakro Mirianashvili, Kvareli district, village Shilda, 1959 – 8 melodies, plus an account about its manufacturing;

Ioseb Patarashvili, Telavi district, village Lapanquri, 1966 – 3 melodies;

Giorgi Menteshashvili, Lagodekhi, 1957 – 5 sheep-herding melodies;

Shalva Javakhishvili, Tianeti district, village Tolenji, 1959 – 5 melodies.

Audio examples:

Shalva Mirianashvili – Tushetian tune. Shilda, 1959. Georgian Folk Music – Eastern Georgia. V. Sarajishvili Tbilisi State Conservatoire, Department of Georgian Musical Folklore, 2007.

Shalva Mirianashvili – Shepherd’s tune. Shilda, 1959. Georgian Folk Music – Eastern Georgia. V. Sarajishvili Tbilisi State Conservatoire, Department of Georgian Musical Folklore, 2007.

Shalva Javakhishvili — Meghoruli. Tolenji, 1959. Georgian Folk Music – Eastern Georgia. V. Sarajishvili Tbilisi State Conservatoire, Department of Georgian Musical Folklore, 2007.

Public Broadcaster Archive (year and location unknown):

Five tunes performed by Piruz Aliashvili, recorded at various times;

Shepherd’s tune performed by Ivane Raibuli;

Shepherd’s tune performed by Shalva Mirianashvili.

Participant of the Republican Competition of Amateur Artists, member of the singers’ ensemble of the Sighnaghi District Culture House; I. I. Raibuli performs “Tushuri” on the salamuri, 1959. © National Archive of Georgia.

Particular mention should be made of the phonograph wax cylinder recordings,[11] where in some cases it is explicitly stated that the performance features the ueno salamuri, while in others, this can be inferred from the performer or the sound characteristics of the recording.[12]

Simon Janashia National Museum Collection: Collection of unidentified tape recordings:

Unknown performer, Kaspi district, Metekhi village – Lekuri dance;[13]

Mta-Tusheti

Aleksi Ekvtimeishvili (location not specified), 1947 – 4 tunes played on the salamuri.[14]

From the collection of Shalva Mshvelidze:

Kakheti[15]

Akop Khachaturyan, Alvani village, 1929 – 2 Tushetian tunes on the salamuri.

Aleksi Ekvtimeishvili – Chobnuri (Shepherd’s tune) – Voices from the Past: Georgian Folk Music from Phonograph Wax Cylinders. 2006. Tbilisi: State Museum of Cinema, Theatre, Music and Choreography; Ministry of Culture, Monument Protection and Sport of Georgia; Tbilisi State Conservatoire.

Aleksi Ekvtimeishvili – Lament – Voices from the Past: Georgian Folk Music from Phonograph Wax Cylinders. 2006. Tbilisi: State Museum of Cinema, Theatre, Music and Choreography; Ministry of Culture, Monument Protection and Sport of Georgia; Tbilisi State Conservatoire.

The audio materials listed above amount to a total of two hours of unique recordings, through which we can identify the scale (tonal structure)[16] of each ueno salamuri, analyse playing techniques, and trace the origins of various ancient tune variants. In short, these recordings provide rich material for scholarly research.

The Ueno Salamuri in Georgian Cinema

Unique video footage of ueno salamuri performances has also been preserved in Georgian cinema, notably in the following films:

Alaverdoba (1962) – footage of Piruz Aliashvili playing the ueno salamuri (24 min), which is of particular importance as it clearly captures the nearly forgotten technique of circular breathing used in salamuri performance;[17]

Pirosmani (1969) – a shepherd’s tune performed by Piruz Aliashvili (54:05 min);

Shemodgoma (1994) – scenes depicting the crafting of a ueno salamuri by Giorgi Okrotsvaridze.

It is also noteworthy that traditionally made ueno salamuris have survived to this day. These include highly professional, hand-crafted and ornamented examples housed in the Museum of Georgian Folk Songs and Instruments at the Palace of Arts, as well as handmade instruments collected during expeditions conducted by the G. Chkhikvadze Laboratory of Ethnomusicology at the Tbilisi State Conservatoire.

A Continuous Tradition to This Day

In addition to the sources listed above, many other stories about the ueno salamuri have been preserved in people’s memories, including recollections of Piruz Aliashvili’s playing (as heard and recorded by me personally). Aliashvili was a frequent guest in many homes across Kakheti. After a glass or two, he would often take up his salamuri and play — tunes that became sweet childhood memories for many.

Piruz Aliashvili. 7th Olympiad of Amateur Performers of Georgia. 1951, Tbilisi. © Archive of the A. Erkomaishvili State Folklore Centre of Georgia

Memories also live on among the people about ancestors who played the ueno salamuri. In some families, the instrument itself has been preserved as a unique relic. For example, the ueno salamuri of Ivane Raibuli is still kept in Sighnaghi, and that of Aleksi Ekvtimeishvili in the village of Kakabeti.

(from left to right): 1. Ueno salamuri made by Ivane Raibuli, kept in Sighnaghi 2. Ueno salamuri made by Aleksi (Mikhako) Ekvtimishvili, kept in Kakabeti 3. Ueno salamuri housed in the Museum of Folk Songs and Instruments at the Palace of Arts 4. Ueno salamuri preserved at the G. Chkhikvadze Laboratory of Ethnomusicology, Tbilisi State Conservatoire

Most importantly, at the time of writing, the 86-year-old performer Zaur Tetrashvili — who is a direct heir to the ueno salamuri performing tradition — is still alive. The knowledge he has preserved regarding the making and playing techniques of the ueno salamuri closely matches and complements the information found in the sources listed above. This calls for an in-depth study of both the tunes he performs and his technique.

Based on the information currently available, here is a map of ueno salamuri performers by place of origin. See the link (map subject to updates).

And is the ueno salamuri truly a museum piece? The main aim of this article has been to introduce the reader to the rich heritage passed down to us in the form of the ueno salamuri. At the same time, I believe it is for the reader to decide: should we study and continue the unbroken tradition left by our ancestors? Does this unique instrument deserve its place among the great folk instruments of the world, or should it be preserved only as a museum piece — a relic of the past, a distant echo of our ancestors?

[1]Sounds from the Past – Georgian Folk Music from Phonograph Wax Cylinders. 2006. Tbilisi: State Museum of Cinema, Theatre, Music and Choreography; Ministry of Culture, Monument Protection and Sport of Georgia; Tbilisi State Conservatoire.

Georgian Folk Music – Eastern Georgia. Tbilisi: V. Sarajishvili State Conservatoire, Department of Georgian Musical Folklore, 2007.

[2]This issue is addressed by Ana Lolashvili in an article in the previous issue, No. 6 of the magazine.

[3]See the list of audio materials of salamuri preserved at the Tbilisi Conservatoire.

[4]Tsida - an old Georgian unit of measurement, defined as “the distance between the tip of the index finger and the thumb” (N. Chubinashvili). In the metric system, it is equivalent to 12.65 cm.

[5]Javakhishvili, Ivane. 1938. Key Issues in the History of Georgian Music (ქართული მუსიკის ისტორიის ძირითადი საკითხები). Tbilisi: Federatsia. 200 pages.

[6]Arakishvili, Dimitri. 1940. Description and Measurement of Folk Musical Instruments (ხალხური სამუსიკო საკრავების აღწერა და გაზომვა). Tbilisi: Teknika da Shroma, p. 11

[7]Belyaev, Viktor. 1936. On the Study of Georgian Musical Instruments [К вопросу изучения грузинских музыкальных инструментов]. Proceedings of the State Museum of Georgia IX-B. Tbilisi: S. Todria Printing House “Kommunisti,” pp. 1–40.

[8]Rosebashvili, Kakhi. 1979. “On the Issue of Reviving the Georgian Folk Bagpipe” (ქართული ხალხური ჩასაბერი საკრავის აღდგენის საკითხისთვის). Collected Works (Tbilisi Conservatoire), Issue 7: 113-133.

[9]Chkhikvadze, Grigol. 1962/63. Georgian Musical Folklore (ქართული მუსიკალური ფოლკლორი). Unpublished manuscript. G. Chkhikvadze Laboratory of Ethnomusicology, Tbilisi State Conservatoire.

[10]Shilakadze, Manana. 1970. Georgian Folk Instruments and Instrumental Music (ქართული ხალხური საკრავები და საკრავიერი მუსიკა). Tbilisi: Metsniereba.

[11]Voices from the Past – Georgian Folk Music from Phonograph Wax Cylinders. 2006. Tbilisi: State Museum of Cinema, Theatre, Music and Choreography; Ministry of Culture, Monument Protection and Sports of Georgia; Tbilisi State Conservatoire.

[12]For example, if it is known that a specific person played the ueno salamuri, but the description only generally mentions “salamuri,” it is clear that the recording refers to playing the ueno salamuri. Sometimes, if the recording is damaged or flawed, making it difficult to identify the instrument, information about the performer (especially if we know exactly which instrument they played) helps us determine the type of instrument.

[13]This recording confirms the presence of ueno salamuri performers in the territory of Kartli.

[14]Alexi Ekvtimishvili is mentioned in a letter from I. Mchedlishvili: “... I recorded this in the village of Kakabeti from Alexi Ekvtimishvili, whose ‘Ueno Salamuri’ was recorded on the phonograph after the folk concert I gave at the Conservatoire on 13 February 1928. I. Mchedlishvili.” See: Javakhishvili, Ivane. 1938. The Main Issues in the History of Georgian Music. Tbilisi: Federatsia. p. 200.

[15]Based on their sound characteristics, the two recordings included in this collection can only be assumed to be recordings of the ueno salamuri.

[16]The dimensions of the ueno salamuri were taken from parts of the palm. Consequently, each salamuri player had their own unique size and scale of the ueno salamuri, corresponding to the proportions of their hand. As this matter relates to a significant musicological issue — the musical tuning and scale system of Georgian traditional music — a dedicated study will be devoted to it and published in the next issue of the magazine.

[17]At this moment, the performer continuously plays the melody by controlling the airflow.