The Yard-Keepers of Tbilisi: Invisible Heroes Living Next to Us for Centuries

If we could travel back in time and take a look at the Tbilisi of past centuries, alongside the bathhouse attendants, porters, water carriers, watchmakers, and representatives of other professions that have already disappeared, we would definitely notice the meezovebi: sweepers or “yard keepers,” from ezo (courtyard). When we think of meezovebi, the first image to come to mind is likely the famous painting by Niko Pirosmani (1862–1918), titled “Meezove,” from around 1905, or the statue based on the same work, which can still be seen on Baratashvili Street. The history of this profession, however, begins much earlier and continues much later. With the passage of time, Tbilisi’s appearance may have changed, but the Tbilisi yard keepers have not disappeared anywhere; they start every morning next to us, if always earlier than us.

Tbilisi, like cities throughout the world, underwent a process of major urbanization throughout the nineteenth century, naturally leading to the need for street sweepers. For much of this early period, however, their professional duties were not limited to cleaning the city. In the 1880s, by order of the Russian viceroy, the Yard-Keepers Institute (meezovis instituti) was established in Tbilisi. Around that time, the mayor of Tbilisi resettled 2,000 people from Armenia in the city, many of whom became members of this Institute. The 1902 edition of the journal Iveria includes the list of the mandatory rules for the meezovebi, introduced by the governor-general in 1901. As we read in this list, yard keepers, in addition to cleaning the city, were also responsible for keeping an eye on the people of Tbilisi:

- To keep an eye on everything that happens on the street, those coming and going from the houses, especially suspicious persons. Those who come out of the houses with sacks and other things in their hands.

- To keep eyes and ears out for gatherings of suspicious people in houses. The district police chief should be immediately informed when such a gathering happens.

The subject of the Yard Keepers Institute was widely discussed at a meeting of Tbilisi’s city government on February 7, 1905. The focus of the session was the meezovebi’s right to spy on the city population. Although attendees demanded that the meezovebi be released from their service to the police, the Institute operated until 1914.

Throughout the existence of the Yard Keepers Institute, the meezovebi themselves also repeatedly requested to be released from policing duties. Around the beginning of the twentieth century, meezovebi always joined in strikes with construction workers, conductors, mechanics, and other workers in Tbilisi for the improvement of labor rights. For example, an issue of the newspaper Shroma from 1906 reports that twenty-two meezovebi employed by the Tbilisi State Bank went on strike, demanding to be exempted from police duty and night guard duty. In the following issues of the newspaper the demands of the striking meezovebi in all parts of Tbilisi were formulated in more detail:

Twenty-five rubles should be given to each meezove as a monthly allowance [...]

- The owner of a house should not be able to fire a meezove for no reason. If he is dismissed, he should be given three months’ compensation [...]

- The meezovebi should not have any affiliation with the police [...]

- The duties of the meezovebi include: yard cleaning, street cleaning, keeping watch, etc. As for the servants of the owner of the house, the owner should not have the right to use a meezove as a personal servant [...]

- No one shall be fired for striking.

After 1914, the meezovebi gained the freedom they had been demanding for so long. This was partly due to the historical context: with the growth of the revolutionary movements in the Russian Empire, its influence weakened, and Georgia became an independent republic in 1918. Naturally, the change in government was accompanied by innovations in various fields: new professions appeared, and old ones were forgotten, but yard-keeping does not really fall into this category. It is one of the indispensable professions, and after the meezovebi were released from police duties, the appreciation and respect for these people from the society and the government became more visible. As we read in a 1953 issue of K’omunist’i, Tbilisi’s main party newspaper, a discussion was held in Tbilisi on promoting the culture of sanitation. At that meeting, the first secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Georgian SSR, Akaki Mgeladze, made a long speech about the creation of an exemplary sanitary culture in the city, repeatedly emphasizing the contribution of the meezovebi. As Mgeladze remarked at the meeting:

If a factory worker does his job well, if he is a Stakhanovite [i.e., recognized for high productivity], everyone pays attention and respects him, supports him, rewards him, gives him a good apartment. His portrait is hung in a prominent place, they write about him in the newspaper. But a meezove? No matter how good of a job he is doing, not a word! How can we achieve exemplary sanitation and cleanliness in the city if we ignore the very people who work directly on this matter? The solution should be to change the attitude towards the meezovebi, to strengthen their role in the struggle for improved sanitary culture, to create suitable conditions for them to work.

This is not the first time when newspapers of the last century emphasized the work of the people who took care of the cleanliness of the city. No matter the weather or other obstacles, the meezove’s workday always ends just as everyone else wakes up. It is really difficult to ignore the work of those people who often take our share of social responsibility upon themselves, and so it is not surprising that, at various times throughout the twentieth century, residents wrote about individual meezovebi in the press.

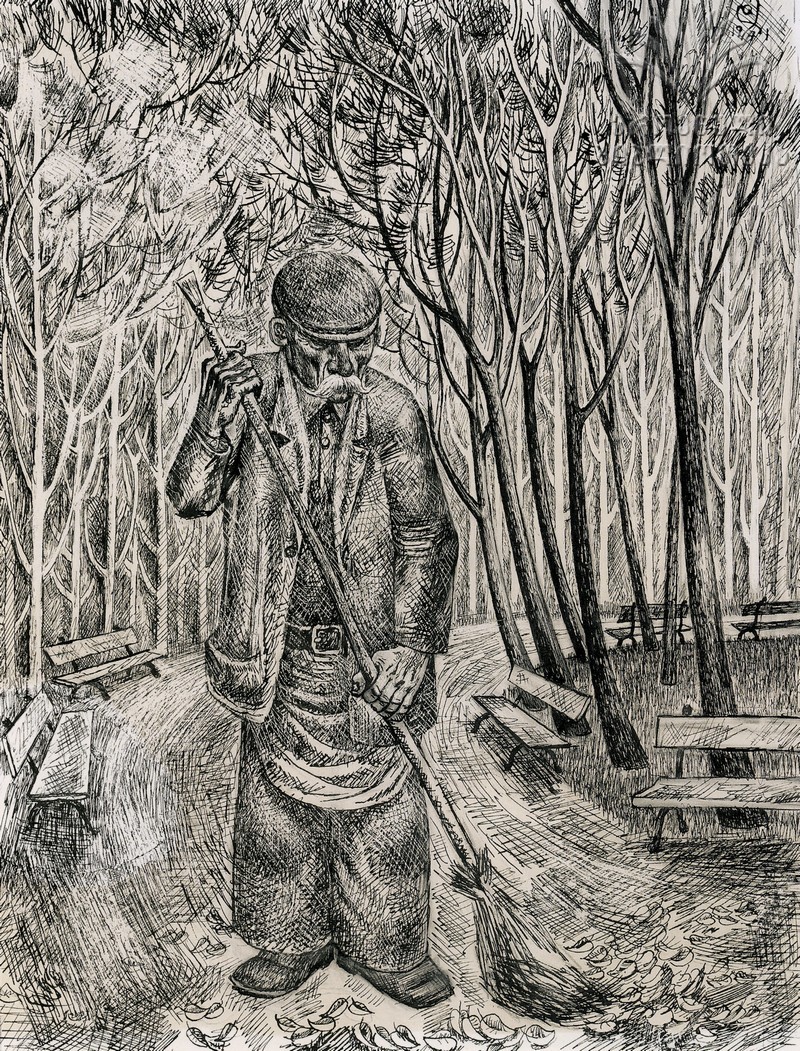

"Meezove" by Dimitri Eristavi, from the " Workers " series , 1971

In 1986, for instance, there was a retirement ceremony for the meezove Karo Mkhitariani, who was highly respected by the people of Tbilisi. The July 4, 1986 issue of Tbilisi featured an article dedicated to Karo, in the column “The People of Our City”:

Karo Mkhitariani is Armenian, born in Bryansk district and raised in Tbilisi. He chose yard keeping as his profession. And he wasn’t wrong in his choice. For fifty years—almost half a century—you have been dedicated to your work, never warranting a single remark or reprimand. This means that you chose the right profession, you are doing what you love. You do it and it makes you happy.

In a 1959 issue of the same newspaper, this time in a column about people with ordinary professions, we read about the hard work of another elder meezove, Konstantine Aliozovi:

Konstantine was born in Kars and experienced some difficult times there in his childhood; even now these memories bring tears. He remembers every day like it was yesterday. And how could he forget the day in 1918, when he first set foot in Georgia. He was fascinated by the beauty of our country, and he came to personify it. When you look at him, you can’t help but be reminded of the famous painting by Pirosmani— the meezove with a white apron and a long broom in his hand—but with the difference that our meezove looks at us with more vivacity and contentment. The light of a happy present and a bright future shines in his heart.

It is clear that the residents of Tbilisi have always appreciated the work of the meezovebi. However, we must also consider the censorship, characteristic of the totalitarian regime, which applied to these press reports. Of course, the stories of the people who were unjustly executed by the Soviet regime could not appear in the pages of the old newspapers. Since the regime was merciless to everyone, people of any profession could be persecuted. The meezovebi were no exception: the regime rewarded them with one hand, talked about improving their working conditions, and destroyed them with the other.

In her book What I Remember and How I Remember, the film director Lana Ghoghoberidze recalls her past life and depicts twentieth-century Tbilisi and Georgia in a sobering light. One of the sections of the book tells the story of the capture and shooting of a meezove named Abo, a reminder that not all yard keepers looked at us with a broom in their hands, satisfied with life. In Ghoghoberidze’s account:

A large family of Kurds lived in the dark, damp basement of our house. This was a manifestation of Soviet humanism and fair national policy: Kurds lived only in basements and worked as yard keepers. For us, as children, this kind of discriminatory attitude was completely alien, and we made friends with our Kurdish peers without any problems. But a strange thing happened one day, when we heard in the yard that our Kurdish meezove Abo had been arrested.

The author goes on to describe Abo’s wife, Zarikula, who, for just one day, believed that her husband’s arrest and the government’s actions had somehow moved her to another, higher social category. However, the next day, Zarikula was back to work, holding Abo’s broom in her hands, and a few months later Abo was executed.

Pirosmani, “Meezove.” National Museum of Georgia

One side of the meezovebi’s history is what we read in old newspaper clippings; the other is how the life of these people was reflected in the culture. Many poets of the twentieth century wrote short or long poems about the meezovebi. As we’ve already noted, one of the best-known examples in visual art is Pirosmani’s painting, titled “Meezove.” Pirosmani’s paintings often portrays the people, professions, and situations that were part of the daily routine of Tbilisi during the artist's lifetime. In such portraits as “Cook,” “Workers,” “The Beauties of Ortachala,” and “Meezove,” the artist’s simple and distinctive style provides us with some details about the general aspects of these people’s daily lives, while leave the interpretation open to the audience.

When it comes to Pirosmani’s “Meezove,” there is some controversy regarding interpretation. Firstly, the exact date of painting is unknown; having this knowledge would probably give us a better insight into the artist’s intentions. Some suppose that the meezove depicted in the painting is a Yazidi, Rashid Adamovi. The fact that the meezove in the painting is holding a cane instead of a broom has also been interpreted in different ways. According to one version, he is holding a baton instead of a broom because he is the face of the Russian police regime, during the period when the Yard Keepers Institute still existed. However, from another point of view, this detail has more to do with Pirosmani's style. Gaston Buachidze, the author of a book entitled Pirosmani, or the Deer’s Walk,, notes that “because of his age, the meezove is forced to lean on a cane to feel stable on the ground, which crumbles under his feet.” And the fact that the meezove is holding a cane instead of a broom, in the writer’s opinion, indicates the artist's desire to express a more generalized look.

It is important to note that, in the last century, people of several non-Georgian ethnicities also worked as meezovebi, including Yazidis. Yazidis started settling in the Caucasus in the nineteenth century and continued to do so through the beginning of the twentieth century. The last group settled in Georgia around 1914–1918, during the First World War. Since some of the Yezidis did not know Georgian, and education was not available to everyone in Tbilisi at that time, the Yezidis living in Tbilisi were often employed as meezovebi. Because of this, the profession became associated with Yezidis, though this has not been the case for quite some time, and the association endures now only as a stereotype. Today, the meezovebi are employees of the Tbilisi cleaning service, and both Georgians and representatives of other ethnic groups take care of keeping the city clean together.

I spoke with Mzia Mastoyan fifty-two years old, who has been working as a meezove for 14 years. Her workday begins when everyone is asleep, so that when they wake up, people will find the streets, squares, and stadiums clean. As Mzia points out, what she really likes about her profession is the warm attitude of people and the respect they often show towards the meezovebi:

Where I work, the local residents and even strangers respect me; they are always very sweet and warm towards me. My colleagues in the neighboring buildings are also treated very well; there are warm and uncomplicated people everywhere. The result of the meezovebi’s work is that in the morning, when people wake up, the city is already sparkling, you enjoy going to work, taking your child to school or kindergarten. Also, when parents and babysitters take their children out to the parks, their surroundings are clean.

The story of Okropiri Targamadze, who joined the Tbilisi cleaning service in 2015, is also quite interesting. For years he worked as a teacher and taught history, social studies, family ethics and psychology, aesthetics, and Soviet law. As Okropiri recalls, in the 1990s, when unrest took over the country and the currency became devalued, professors and teachers found themselves facing great financial difficulties. Okropiri had four children, so he left the teaching profession and did everything he could to support his family. The Tbilisi cleaning service offered him a later starting time, to which he happily agreed. As he explains,

You have to love your work, and if you do it with love, then this work will not be difficult. I got used to this job and developed a very close relationship with the people. We are always happy to see our colleagues. We have professional friendship and unity, which is nice. As for the work itself, in the process, you can think about something else. I often think about my interests, the history of one country or another, the history of our country or the world, and time passes quickly like that You look up, and you have already finished the work. That is, the work can be done in such a way that you don't even feel it anymore.

According to Okropiri Targamadze, the residents’ satisfaction is the biggest reward for him and other meezovebi. As he recalls, complete strangers on the street often thank him for cleaning the city, a display ofgratitude, which Okropiri thinks should be shared with all meezovebi for doing this work. Although he started in this profession only nine years ago, Okropiri vividly remembers the meezovebi from his youth, who did such important work:

Okropiri Targamadze, employee of Tbilservi Group

In my youth, it was mainly Kurds and Yazidis who worked in this profession, and they wore their national dress, which was very nice to see. Now I ask my colleagues why they don’t wear their beautiful national outfits: they are so shiny, and they wear them beautifully. However, the moment has already passed, and this doesn’t happen anymore but at the time, the city had a special local color. In the 1970s, I remember that people still wore these clothes, but in the 1980s and later, they no longer did. Also, I think that Tbilisi is still unique in terms of the history of the meezovebi. This kind of picture often comes to mind from my younger days, when I had to go to university: imagine it’s six o’clock in the morning and everyone is sleeping, the street is quiet, there are no cars, and at that time you just hear the sound of the meezove’s broom. When everyone is asleep, it is the street cleaners who perform their professional duties, and there is a certain pleasure in it. When it was already almost dawn, and you would hear the sound of the broom, there was a certain pleasure in that too, because you knew that dawn was nigh, and soon a new life would begin.

Such was the life of the meezovebi of Tbilisi in the past, and such are their stories now, stories which continue and are written before us today. Caught up in our own professions, personal affairs, or usual routines, we often do not even notice the people who perhaps contribute most to the care of the environment. The fact is, there are no “easy” professions, and the work of the meezovebi is a clear example of that.

Sources:

1.“Saerto movaleoba meezoveta” (Common duties of yard keepers). Iveria, January 10, 1902 (no. 8), p. 1.

2.“Gapitsva da motkhovnilebani” (Strike and demands). Shroma, June 13, 1906 (no. 56), p. 2.

3.“Motkhovnilebani da gapitsvebi” (Demands and strikes). Shroma, July 21, 1906 (no. 86), p. 4.

4.“Sanimusho sanit’aruli k’ult’uristvis” (Towards an exemplary sanitary culture). K’omunist’i, February 15, 1953 (no. 39), p. 2.

5.Kiknadze, R. “Ch’abuk’uri gat’atsebit” (With youthful enthusiasm). Tbilisi, August 4, 1959.

6.Tkeshelashvili , M. “Gatsileba” [Seeing off]. Tbilisi, July 4, 1986.Taktakishvili, Levan. “Meezove—sisuptavis damtsveli tu damsjeli” (Meezove: defender of cleanliness or a punisher.” Tbiliselebi, October 2022. October 17–23 (no. 42), p. 9.

7.Buachidze, Gaston. 1982. Pirosmani, ili, Progulka olenia (Pirosmani, or the deer’s walk). Tbilisi: Khelovneba. First published in Russian, translated into French as Pirsomani, ou La promenade du cerf. 2018. Nantes: Éditions Coiffard. Quoted here.

8. Kevanishvili, Eka. “Sakartvelos iezidebi” (Yezidis of Georgia). Radio Tavisupleba, October 9, 2015. https://www.radiotavisupleba.ge/a/sakartvelos-iezidebi/27297796.html

Cover image: a group photo of meezovebi (yard-keepers) from Old Tbilisi. "Iveriel" Digital Library of the National Parliamentary Library of Georgia.

.jpg)