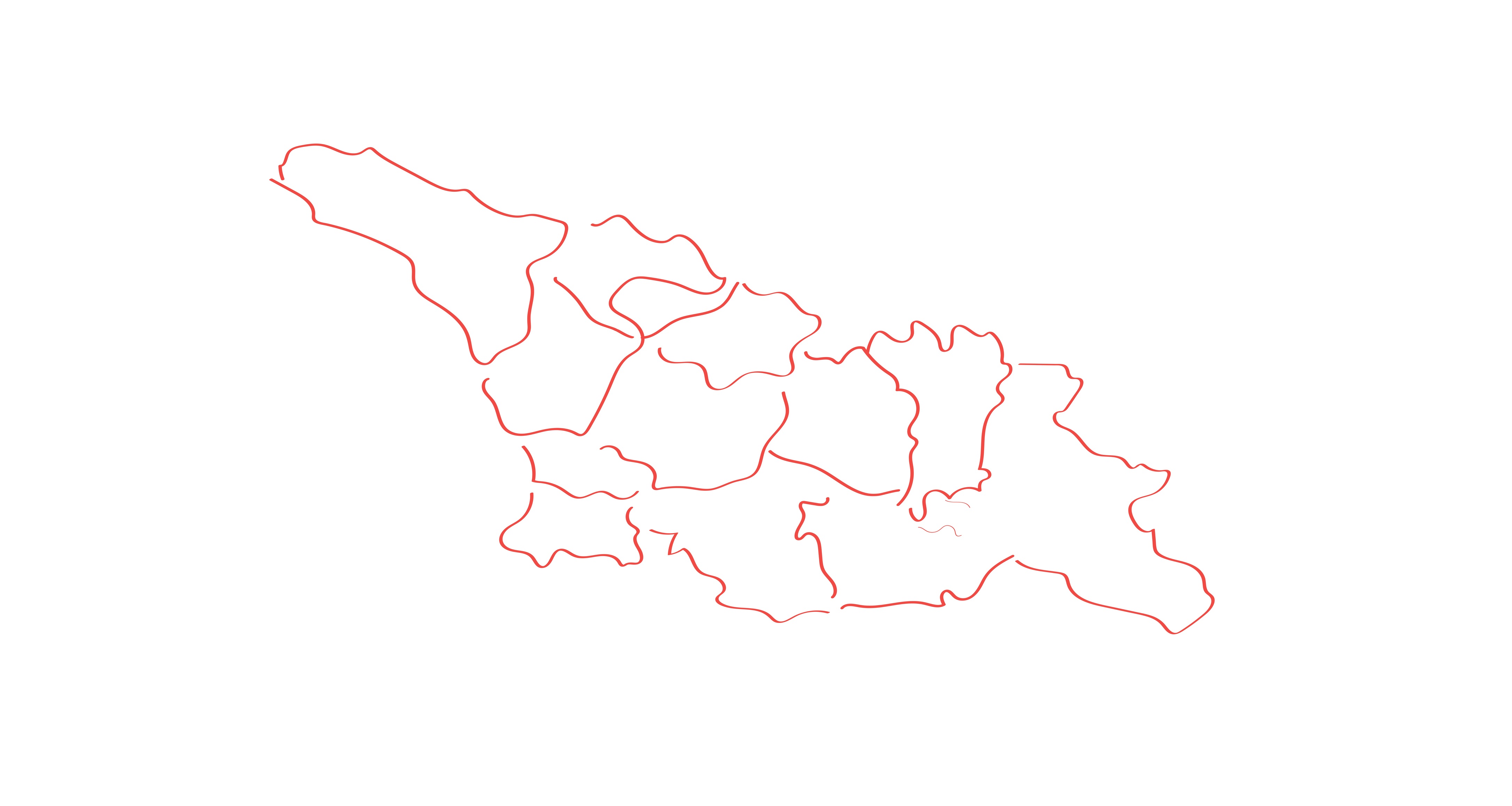

On Some Christmas Folk Traditions in Georgia

As the light of the morning star begins to shine on Georgia’s mountains and valleys on January 7 (December 25 in the church calendar), a special sense of anticipation fills the air. This star also seems to be different, special, as if it is twinkling with excitement. People are delighted, and they were more delighted still in olden times, when the joy and excitement of waiting for the Savior was even more intense.

People get ready according to their traditions and customs. They put on their festive clothing and prepare the best dishes. They cannot wait to celebrate and venerate the one who they believe gave his life for them, the one who gave them selfless love, hope, and loyalty.This is why in Svaneti, they would open a window at night, to let in the Christmas spirit; it is why we welcome the Mother of God with a candle in the window, so that the Savior can come into our hearts and homes.

The religious ritual also begins with food preparation, which is, in fact, an integral part of it. The purpose of the ritual is to transform the person, re-establish order in the world, to give health to the sick, to bring unity and solidarity to people, to connect with the outside world, God, angels, supernatural forces, the past and the future. Basically, three phases can be distinguished in the structure of the ritual: separation, transformation, and reincorporation, i.e. returning again, which is expressed in the shared feast. During the first stage, the ritual participant hovers between two identities: neither here nor there, no longer old and not yet new. It is a state where a person is outside of time and social structures. In my opinion, it is in this phase of the ritual that the physical, mental, and spiritual preparation to meet God begins. The harbinger of the miracle is probably the morning star of this day. People looked to its coming for twenty centuries in our country, and they continue to do so nowadays. And before it appeared in the sky, the fattened Christmas pig was slaughtered, Christmas porridge was cooked, “Christ's supper” was prepared, and Christmas ritual breads were baked for Jesus Christ, family members, and relatives.

In some places, people would start to fatten the Christmas pig—to be slaughtered on Christmas Eve—as early as the beginning of autumn. It was called lekrisdesh in Svaneti, sakirse ghori in Samegrelo, kosmeni in Kakheti, saagebo ghori in Kartli. In some places, the Christmas pig was slaughtered on Christmas Day, rather than on Christmas eve. [1]

During Christmas preparations, baking ritual breads and cooking porridge were the main ritual activities of the day. This was the moment when family cooking would slowly transform into a Christmas ritual. The wheatberry (wheat kernel) porridge had different names in different regions: Ch’ant’ila (Svaneti, Rach’a, Lechkhumi) or K’ork’oti (Imereti, Guria, Samegrelo), Christ’s K’ork’oti (Kartli, Tusheti), tskhrats’vena (Kartli, Kakheti), Sats’andile/Sak’ork’ote. The women had to leave the wheatberries until the sunrise, and then cooked them, flavoring the porridge with onion, salt, and walnuts, or with honey or sugar and walnuts.

On the morning of Ch’ant’iloba, the housewife would get up first, bring the wooden bowl containing the sach’an’tile (wheatberries for porridge) over the middle of the fire, and hit it with her hand three times in such a way that the part of the contents would fall into the flames and catch on fire. After that, they would wash the sach’ant’ile, put it in a pot, and hang it over the fire. When the kernels were well cooked, three grains each of every seed (corn, beans, chickpeas, lentils) were thrown into the cooked ch’ant’ile. The foam of boiled porridge was applied to the trees outside, so that next year the harvest would be abundant. Ch’ant’ile could not be eaten until the evening, before dinner. According to people’s beliefs, in whatever direction the k’ork’oti would spill during cooking, that was where a good harvest would be next year. The tskhrats’vena was mainly made with beans, with the addition of various grains: barley, corn, wheat, millet, sorghum, and chickpeas. As a portent of an abundant harvest, the juice had to be thick. When the tskhrats’vena was cooked, they would pray: “Bring us many peaceful Christmases and New Years.” On the same day, wheat was soaked in water and boiled. The plowman would put the wheat into the water and stir it with a stick from a pear tree. Then this stick was fixed to the wall of the house and kept for a year. The plowman would skim the congealed “crust” or top layer of the grain porridge and apply it to the rafters or walls of the house, then feed some to the oxen and eat some himself. The ploughman used to feed the k’ork’oti to all the family members with their own hands. The recently bereaved did not make k’ork’oti. Sometimes a thick-bearded man would pick up wheat and throw it into the water , saying, “We will have plentiful harvests.” Sometimes a boy would cook the flour, take it outside and look toward the thickest part of the forest, hoping for the abundant harvest. (These customs are seen in Mtiuleti, Gudamakari, and Ertso-Tianeti.)

© Nino Peradze

On this day in Zemo Svaneti, mujori was made from hemp seeds. Mujori consists of ground and strained hemp seeds, or walnuts, which are mixed with salt and used as a condiment. At dinner, two tables were set, one for the living, and the other for the dead. They prayed and mentioned Lamaria and Krisdesh (Christ). The mallet and spoon, which were used for Christmas, were set aside after the ritual and saved for the next Christmas. It should be said here that on this day and all holidays, all over Georgia, together with the living, the dead were also commemorated.

Ritual breads were also a necessary offering of this day. In Rach’a, they used to bake three walnut pies for dinner. Four candles were made: three were stuck, one each, into the three pies, and the fourth one was held by the woman of the house or the head of the family. A pie with a lit candle, a glass of wine, and placed in a wooden bowl used for the ch’ant’ile grain. The person saying the prayer, a woman or a man, would turn this bowl, near the flame, from right to left three times, and bless it with the following prayer: “God, however many nuts are here, bless us with as much kindness, give us as many barrels of wheat, give us as much wealth and goods!” After the prayer, the person praying would place the four burning candles in the four corners of the house and would not touch them until they burned out. Then the family would sit down for dinner, they would pour the ch’ant’ile into bowls — if they had distilled oil, they would also pour the oil into the bowls, and eat it. Guests were fed ch’ant’ile and pies. In Lechkhumi, in the evening, for dinner, the elder woman baked three small pastries (they were called khveli t’abla). The pastries had walnuts and onions in the middle. Together with the ch’ant’ile, the pastries were arranged in a wooden bowl. On the edge of the bowl, incense was placed onto embers, or a candle was lit. The hostess would take three pastries and a glass of wine, place them at the base of the hearth, and rotate them three times to the right and pray: “God, protect us from coughs and ailments, give good health to the cattle, to people’s souls, take care of us and help us, as you can.” After this, at dinner, it was time to eat ch’ant’ile and pastries. If there was ch’ant’ile left over, they would not serve it on Christmas or the next day, because ch’ant’ile could not be eaten on those days. But after Christmas, everyone could eat it.

There was also a tradition of baking hand-pies and “stomach blessing” pastries on Christmas Eve. One egg was laid in each roll. However many members there were in the family, they baked as many rolls. In Guria, on mravalts’loba, December 24 (January 6), they used to prepare them for Christmas. The main thing during this preparation was to bake the hand pie (a kind of ritual bread). It was a crescent-shaped pie made from wheat flour and filled with cheese and dried fruit, smoked eggs, whole or cut in half. One pie was baked for each family member—bigger ones for adults and smaller ones for children. Christmas pies were also baked in the names of the deceased in the family.

In Khevi, they would bake two q’orbouli, or Christ’s bread. They also did this in Mtiuleti, and the head of the family had to take the bread outside, look at the sky, and say a prayer. Then he would put the bread on his knees, look at the forest, break it, and go home.

In Erts’o-Tianeti, three decorated pastries, krist’es okhshami, were baked and a certain ritual was performed.

In Tusheti, children were instructed to collect keripkla (a tall, thick-stemmed flower) and small pine branches. In the evening, they attached a branch to the door as protection from evil. Everything borrowed was returned on this day: on the night of Christmas and New Year’s, all things, livestock, and people had to spend the night under their own roof. This practice was also common in other parts of Eastern Georgia.

In the evening, after the woman of the house would put the ketsi (clay pan) in the fire, they would stay inside, and nobody could take anything outside of the house. The woman of the house baked ritual breads with images of people and domestic animals. They were called “blessings” and had to be put out for “Christ’s feast.” The long dough was given the shape of a person, like the body of a man. The round dough was extended on four sides — this symbolized the cow’s udders. The body of a sheep was the same, only two udders were made instead of four. A horseshoe would be baked as a stand in for a horse. There was also one big k’ot’ori (tushetian khach’ap’uri), which was called Christ's Food. They would lay out all the breads, k’ork’oti, half of Christ's k’ork’oti, kalti (curd), or a small piece of cheese, a little wool, and a small vessel of alcohol, on a wooden platter with one candle affixed to it. All this was called Christ’s supra. Christ’s supra was kept on top of the ark or in the closet until the designated time (January 5/18). The woman of the house kept the other half of Christ's k’ork’oti for the family. That same evening small breads with holes were baked for each boy who could already bear arms, or a teenager. The breads were placed on small sticks attached to the top of the samatso (men’s) place near the hearth. They could not be taken down. If they didn't fall down on their own, they would have to be eaten by a mice or cats. Bite-sized round breads were baked—satavskvio, “bolster/pillow breads”—and the woman of the house would put one under each family member’s pillow. Similar breads were placed in nests above the doors of the house and the cattle barn, as protection against evil. A bread shaped like a head, with eyes made of pea kernels was inserted into the ashes in the hearth. It looked as if it was peering at the ceiling. This bread had many names: ghomlis deda (ghomli's mother), ch’ichich’q’etia, natsrismdeda (ash-mother), among others. It was the symbol of the hearth’s guardian angel and stayed with the hearth until it burned or was eaten by cats and or mice.

In Khevi, at Christmas, they used to bake ritual breads as well. On this night, the night of Q’orbouloba, they would bake one sakvlevi bread[2], three breads of the Holy Trinity, two q’orbouli or Christ's breads, and seed bread. Each time a loaf of bread was baked, the dough was cut into a cross. Only q’orbouli had its own stamp in the shape of a cross. Bediskveri (fate’s breads) were baked for children, and those, whose breads rose during baking were predicted to have a lucky year. Q’orbouli and fish were eaten on the same night, bediskveri and sakvlevi kept for the New Year, and seed bread — until the spring sowing. Some would bring q’orbouli, fish, and vodka to the fire and say a toast for the souls of the dead; In the same evening, a bread should be baked, which be steaming — steam rising high would bring mercy to the souls of deceased.

On December 23 (January 5) in Kartli, and on December 24 (January 6) in Kakheti, Ertso-Tianeti, Gudamakari, they celebrated tkhiloba, pkhotsaoba/khotsaoba. Adults threw nuts to the children, and they had to collect as many as possible. They played a guessing game, “odd or even.”[3] In Gudamakari, the head of the family distributed a bowl full of nuts and dried fruit to the children, after putting it over the fire and praying for the dead.

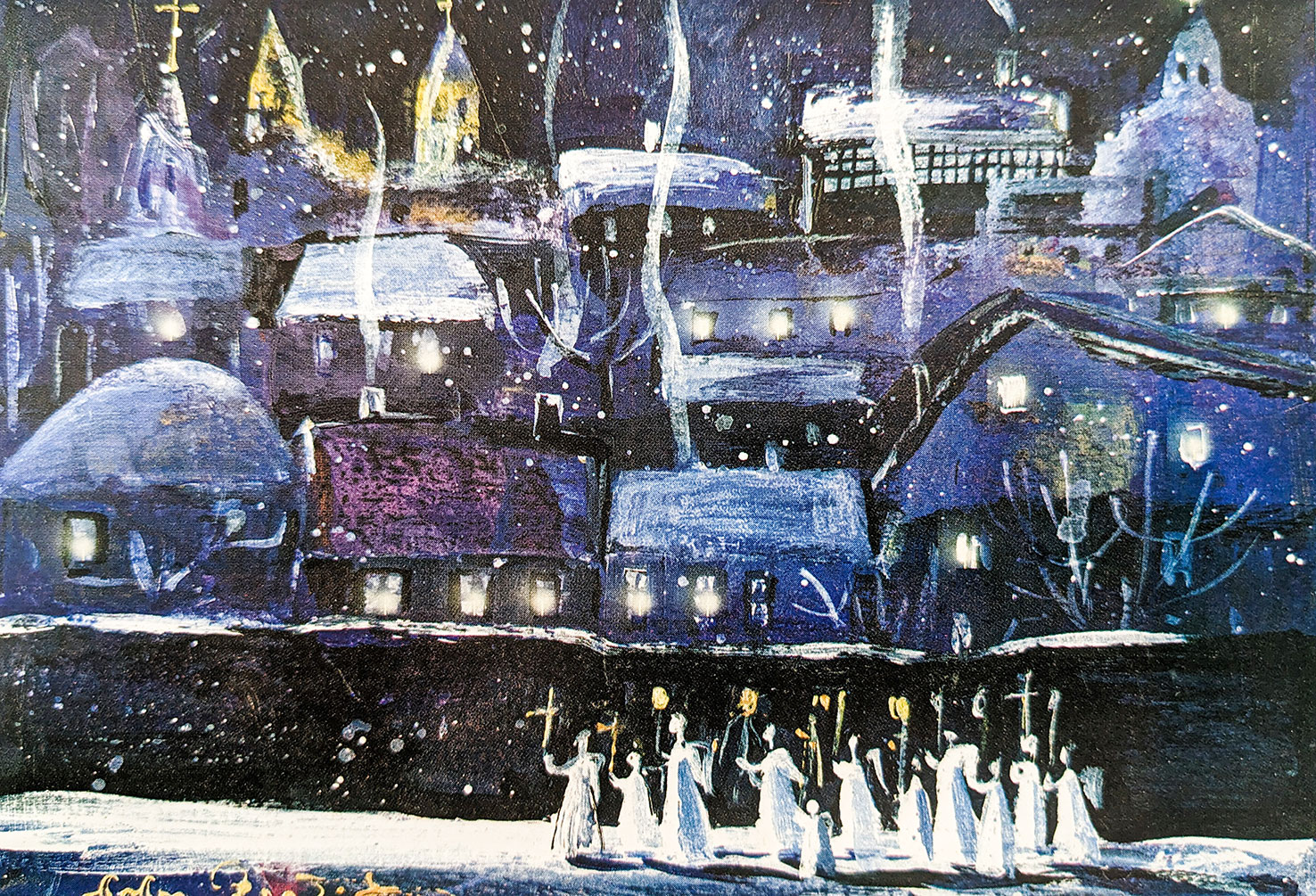

© Nikoloz Gogashvili

The pig was killed. The ritual games of pkhots’aoba also went well. And here, the morning star gave a sign to the harbingers of Christmas, the ritual shepherds—mealiloeebi—that they, like the shepherds and angels from the gospel, could celebrate with songs and chants, that Christ, who would conquer death by resurrection, was born in Bethlehem. The savior was born. Hope was born. God was incarnated.

Alilo (“hallelujah,” commonly translated as “praise the Lord”) is known as a Christmas carol that was performed on Christmas Eve. According to tradition, adult men, dressed in robes like shepherds, went door-to-door to every family in the village, shepherd’s crooks in hand, and sang, rejoicing that Jesus Christ was born. For this, they were presented with eggs and, in some regions, pre-baked ritual breads intended for them. Mealiloeebi, i.e. carolers or “heralds of Christ” (krist’es makharoblebi) were given money and various provisions that the family was able to set aside for them. With all the collected goods, they would celebrate together at the last house they’d come to, or elsewhere, at a place of their own choosing. In some places Alilo was also considered a chant, and in some places they said that if a person sings Alilo to you, it is the same as receiving a great gift. In some places, the mealiloeebi would walk in disguise so that they could not be recognized, and in some places they accompanied the melody of Alilo on the chonguri.

The texts of Alilo and accompanying melodies are especially diverse and varied, and the differences are more or less regional. So for example:

On the twenty-fifth of this month,

Christ was born in Bethlehem

You gave us change,

Bless you, children! (Samegrelo)

***

Alatasa, Malatasa,

put your hand in the basket

take out two eggs

God will give you plenty (Imereti)

***

On the twenty-fifth of this month,

Christ was born in Bethlehem

This lady is beautiful

She throw us coins. (Kvemo Svaneti)

***

Alantasa, Balantasa

hang the basket

Lady, give me one egg

God will bless you.

The bird sat on the fence

Calling for raisins

God bless you all

On Easter and at Christmas." (Meskheti)

On the twenty-fifth, Christmas dawned,

May the grace of Christmas come to you, Christ is born.

Who built this house? Who roofed it with an oak's heart?

May the mother of the builder, and the soul

of the one who roofed it be blessed!

I looked in the window, you had melted butter in jars,

Bring it when you come out, otherwise we will leave swearing.

Alatasa, Balatasa, eggs should be in the basket.

We have slaughtered a pig here.

It was improper to let the carolers go empty-handed: they could curse you, which was obviously a bad omen for the family.

Oh, good fortune is yours.

Our merry lady, the door of the cellar calls for you

Open the wine jar for us, wet our throats! (Kakheti)

In addition to the observance of folk rules and rituals, on this day people attended holiday church services, after which they would break their fast. Then people would visit each other and traditional Georgian festivities would begin. On Christmas, early in the morning, they used to have a special breakfast, which was called dilis khatsitsi (ochumaresh khatsitsi in Samegrelo). Imeretians followed the same rule; they would pray before dawn on Christmas day and then have breakfast. On this day in Guria, gifts were sent to in-laws on the woman’s side: Christmas pie, beef or cow, turkey, wine, baked breads, and khachapuri.

In the village of Shilda (Kakheti), the inhabitants went to Nekresi to pray and slaughter sacrificial pigs or lomtakh. According to the legend, after one raid, the Georgians set male pigs on the Leks, laden with booty, and finally, let them go, but empty-handed. It is after this story that pigs are sacrificed at the shrine of Nekresi at Christmas. In the mountains of Eastern Georgia, the main ceremonial rituals were performed in the shrines. At home, they prepared typical mountain food: khinkali, meat from the slaughtered animal, porridge, boiled rice, and other dishes. Sometimes, the bereaved would sacrifice an animal in the name of the newly deceased. It was a rule in Khevi that before the first anniversary of someone’s death, seven supras had to be set for the deceased, and one of them was during the Christmas period. On this day, it was customary to visit the grave. In Tusheti, in the morning, one of the family members would silently bring water, which was used to prepare dishes for the Christmas feast. During the day, the members of the same clan visited each other, and in the evening it was time for the shiq’ara (village gathering, assembly). Young people used to gather food for the shiq’ara. In some places, they would eat the food collected during the Alilo caroling. On the night of shiq’ara, the nate (a cleric) would choose the makalates: two men and two or three women, who would help entertain the people gathered at the shrine on nates ts’elts’doba (New Year’s) celebration.

In the mountains of Eastern Georgia, the priests would go to the shrines on Christmas or New Year’s Eve. They would begin purifying themselves early. They would go to stay in a “clean” place (for example, in Khevsureti, in the ch’erkho, the top floor of traditional Khevsur house), they would cease having marital relations, and they would not go to unclean places. On Christmas Eve, they had to bathe in the mountain river, submerging themselves nine times as part of the ritual of purification. Before the feasting and drinking that followed the night service could start, everyone would break their fast with porridge. Bowls for the porridge were placed on a low table near the fire, and the elder would pour erbo (clarified butter) into the fire three times: if the flame really flared up, this was the sign of a good year to come. Only after that would they eat porridge, and the zedamdegebi (overseers) would serve beer to those present. Everyone would stay up through the night. At dawn, the priests would drink the vodka sent from the village, then wash their hands and face, and conduct the Divine Liturgy, after which worshipers would come to the shrine.

In this way Christmas days would pass for us, the main prayer of which was the wish of Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, good will toward men.

[1] “Ghori” is the Georgian word for pig.

[2] Sakvlevi, in this context is connected to “mekvle” (first-foot), and refers to the food/drink offered to first visitors on the New Year

[3] One would guess how many nuts are in someone’s fist

Cover image: © Nino Peradze