Khorumi, the Sacred Dance of Georgian Warriors

For the ancient Georgian tribes located at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, combat was one of the main tools of self-preservation.

It would not be surprising to find, in the folklore of such people, who seem genetically pre-disposed toward fighting, the presence of war dances and marching round dances (perkhuli).. About a dozen examples of ancient round dances with themes of war and patriotism have been preserved to this day in Svaneti alone. Pieces such as “Iav Kalti,” “Gaul Gavkhe,” “Lashgari,” “Rost’om Ch’abigv,” and others, are pearls of the national choreographic treasury. (1)

Among the Georgian war dances performed on stage, the Khorumi is one of the most popular; it would be hard to find a folk dance ensemble in Georgia that does not have this dance in its repertoire. The high status of the Khorumi was confirmed in 2013, when it was officially named a “monument of intangible culture” by the Ministry of Culture and Monuments Protection of Georgia. (The author of this article was part of the panel of faculty experts at the Shota Rustaveli State University of Film and Theater to recommend this declaration, along with U. Dvalishvili, T. Munjishvili, and B. Khintibidze.)

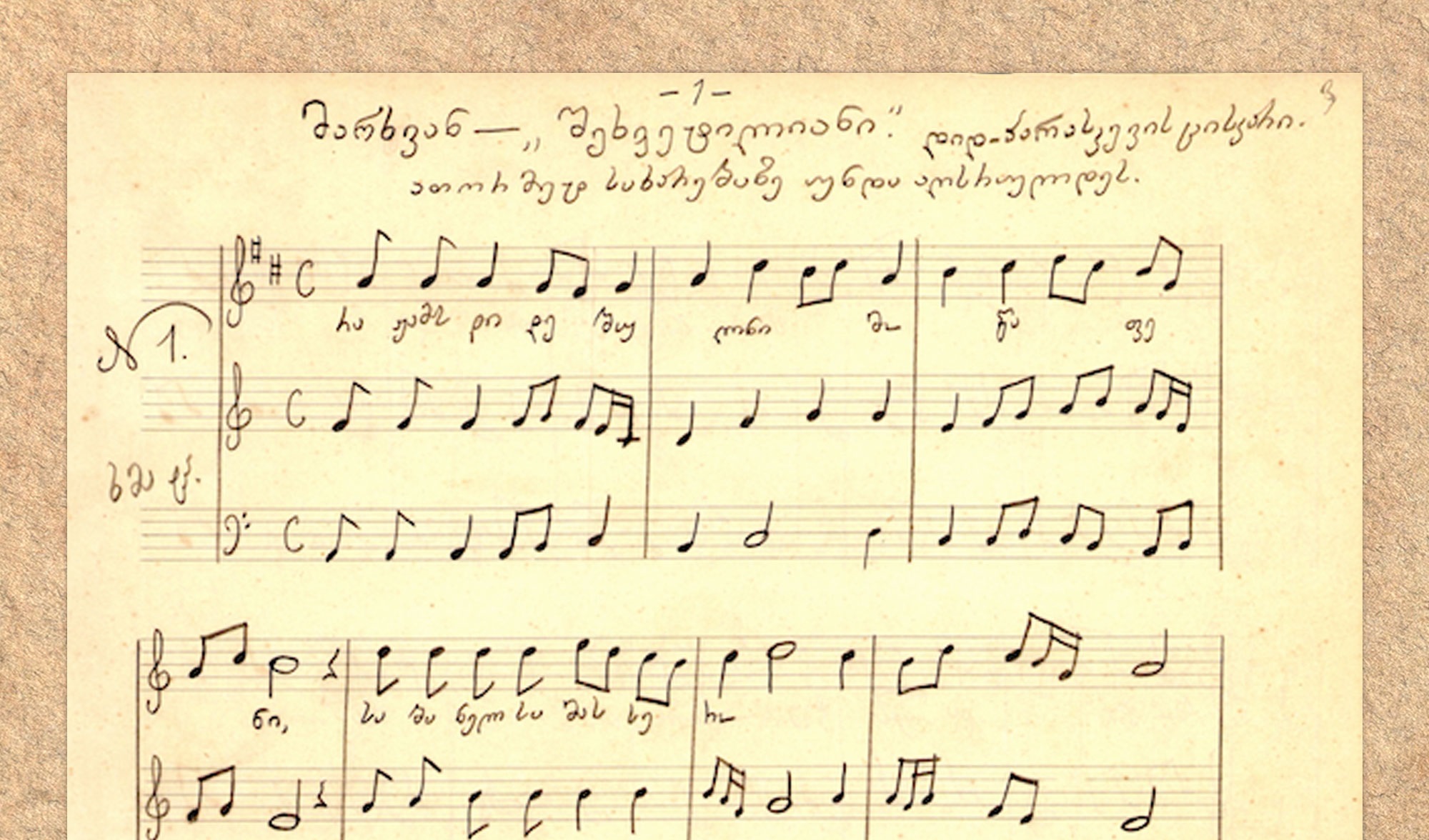

When performed on stage, the Khorumi clearly depicts a battle scene. In the famous ballet “Mzech’abuki” (later known as “Heart of the Mountains”), which was staged in 1936 by the prominent Georgian ballet master Vakhtang Chabukiani, one of the most powerful dramatic episodes was the Khorumi. It is commonly divided into episodes that are linked in one storyline: 1. search for a place to set up camp; 2. surveil the enemy; 3. attack; 4. victory and celebration. This last part of the dance is performed as a gadakhveuli Khorumi".[i] The gadakhveuli Khorumi is fascinating due to its complex melodic flow and variety of moves. It is set in a time signature of 5/8 or 5/4, with prominent rhythmic syncopation. The fourth part of the dance often depicts the commander getting wounded but continuing to fight and lead the warriors, an innovation first seen on stage in 1936, danced by the eighty-five-year-old Aslan Abashidze, from the Khulo district. The Khorumi dance is performed to the accompaniment of a drum, flute, accordion, and sometimes vocals. The costumes consist of traditional clothing from the region of Ach’ara.

The Khorumi includes various ornamental forms of choreographic patterns, including linear formations in one or two rows, and circular formations with one, two, or three concentric levels. In the folk version, the Khorumi usually takes the form of a single line, which then transforms into a circle. There is, however, evidence of the presence of multiple levels in Ach’aran folk practices and descriptive sources.

Anyone who has witnessed this dance in person no doubt remembers the powerful impression that the exposition and finale of this dance creates in the audience. A victorious army on its way home from battle, a linked chain of dancers, back-to-back, led by a commander or leader. The group of dancers immediately follows his lead when the steps change.

As a folk art, the Khorumi dance was widespread in Ach’ara, Guria, and the historical regions of Lazeti and Tao-Klarjeti, whose former territories are located today in Turkey. The dance is notable for its variety of performance methods and movements. The Khorumi is different not only in different regions, but even in neighboring villages. These different communities will often have their own versions of the Khorumi (also spelled khoromi or khoroni), with titles based on place names, such as “Khikhadziruli Khorumi,” “Ts’ablana Khorumi,” “Ghorjomuli Khorumi,” “Kobuleturi,” “Zeda Makhintseturi,” “Ortabatumuri Khorumi,” and many others. They are distinguished from each other by different combinations of steps, stylistic peculiarities, and specific manners of performance. For example, it is known that unlike the Ach’aran Khorumi, the Gurian version is performed in a quick, agile manner. In Imerkheveli, it is often referred to as “Deli-Khorumi,” one of the definitions of which is “squat hop.” (2) It is also called the “fast” or “crazy” Khorumi. Other names referring to the Khorumi (or sometimes khoron) as “old” or “new” are also common.

The etymology of khorumi has been subject to extensive research, though its interpretation is still ambiguous. One common definition of the Khorumi is simply a “Georgian war dance.” The root khor- has been connected with perkhuli (a Georgian round dance), the Greek word khoros (which referred to a group dance and gives us the word chorus), and other, more distant connections, like words for different kinds of Georgian buildings (okhari or akhori in the Chan-Megrelian language and Ach’aran dialect, Svan kor),a place for public assembly (Svan lalkhor), grain used for ritual purposes (khorbali), and the word for “haystack” (khoromi).

The Khorumi dance is still often performed by elders in the highlands of Ach’ara on the Shuamtoba folk holiday. It is worth noting that today several local ensembles act as keepers of its tradition, including the Bermukha ensemble from Khikhadziri, the Dandalo ensemble, the Tskhmorisi ensemble, and several others.

The “plot” of the Khorumi performance is strictly defined and has been canonized with regard to its performance manner and techniques. There must be an odd number of performers in the dance. One of them is the leader, whom the rest of the dancers. The leader, or tavmosame (also known as metauri, ts’inamdzgholi, or khorumbashi) is the first in the line of the dancers and sometimes holds in his hand a fabric head covering or handkerchief known as a baghdadi. The dancer at the end of the line is known as the “closer.”

This kind of round dance is similar, in terms of form and symbolism, to other ritual dances dedicated to fertility, such as “Adrek’ila” and “Melia T’ulepia” (or T’elepia) from Kvemo Svaneti, “O Hoi Nana/Nano” from Khikhadziri, or “Ts’inamdzghola” from Rach’a.

Some scholars have claimed that the Khorumi dance is related to an ancient dance form described by the Greek historian Xenophon (427–355 BCE). In his Anabasis, Xenophon describes how the Chalybes (also called Khalib, whom some consider to be Georgian tribes) sang and danced while the enemy was watching, and the seafaring Mossynoeci, who became Xenophon’s allies and helped the Greeks get across a river with three hundred boats and warriors, “arranged themselves in the following way to meet the enemy: they would divide into groups of a hundred, like teams, and line up, in a precise order, one in front of the other.” He goes on to say that, “before battle, one of them would start a song, and the rest followed the rhythm and marched forward.” (3) Dimitri Janelidze explains that Xenophon himself “likened the arrangement of the players to a Greek chorus, though he also took note of the unique organization of the Mossynoeci’s singing and dancing: ‘They sang and danced in an unusual arrangement.’” (4)

Although there is general consensus regarding the combat-inspired content of the Khorumi, some scholars exploring the dance’s origins take a different position and point to its religious-ritualistic aspects. The dance scholar Lili Gvaramadze agrees about the warlike content of Khorumi while also suggestsing that “a hunters’ dance should be considered a precursor to Khorumi.” (5) Gvaramadze rightly sees in this dance the elements of hunting and totemic dance, among them: the semi-sitting position (something between k’och’a, a full squat, and bukna a kind of squat-hop); acrobatic, gymnastic elements (pundruk’i); jumping movements (bast’i); and the ancient somersaulting circle dance from Meskheti-Javakheti known as tulo. (6) She also references dance components characteristic of fertility rituals, emphasizing the connection of this dance with “Adrek’ila,” a men’s round dance from Svaneti, , which features a leader and is dedicated to the fertility deity.

Revaz Chanishvili has developed a hypothesis about the gadakhveuli or “intertwined” Khorumi, in which he argues that the gadakhveuli part may be connected to the labor process, specifically the action of pressing grapes in a winepress. (7) In the end, nevertheless, he still acknowledges the combat-focused content of the dance.

Despite the presence of choreographic elements related to fertility, the Khorumi’s elaborate battle plot was cited as the reason for favoring its interpretation as a war dance. An observation of the dance movements does indeed support the idea that this war dance is connected to the cult of fertility. For many ancient people, fighting and defeating an enemy, as well as the divine hunt, were understood as symbols of an all-encompassing cosmogonic idea.

Mircea Eliade writes that it was necessary for ancient people, before they entered an uninhabited or mysterious space—chaos, in other words—to place that space in a cosmology. (8) Battle was one such space of chaos. Thus, before setting foot in this chaos, it was necessary to perform rituals that symbolically replicated the act of creation, which is linked to birth and fertility. The performance of the ritual, which implied the victory of the cosmos over chaos, was a necessary and desirable precursor to victory over the enemy. According to Xenophon, a magical dance was connected to victory in battle, and it was performed to the sound of a song. It was based on this information that the historian Ivane Javakhishvili pointed out that Georgians already had war dances and songs from the time of paganism. (9) As Manana Khidasheli notes, “The defeat of chaos, the victory of the cosmos or order, the rebirth of new life from death, the establishment of goodness and light, could only be achieved through struggle. Therefore, in the mythic consciousness, the fight was understood as one of the most important rituals.” (10)

The links between the functions of deities of fertility and war are indicated by the ithyphallic statues found in Georgia, which, both conceptually and physically, show a direct connection with the Khorumi dance. One could associate it with the phallic warriors with girdles around their waists, as well as the Javakhetian tulo somersaulted the main characters of the Murkvamoba and Berikaoba festivals, who have masculine ornaments hanging from their girdles. As L. Pantskhava points out, various types of warrior deities found at the Bronze Age site at Shilda—standing, naked, ithyphallic figures—are decorated with similar accessories like belts, collars, bracelets, or leather belt straps used to lift weights. Some are equipped with helmets, shields, and swords. Some have stripes on their bodies, which converge like the rays of a sun into a circle on the back. (11)

.jpg)

Scholars consider the cult centers of Meli-Ghele II and Melaani (archaeological monuments located in the municipality of Gurjaani which date back to the first or second millennium BCE) as chapels of a war deity, although they also point to the cult of fertility. The statues of the Melaani shrine are warrior deities who have not yet lost their connection with fertility. In them, both functions are emphasized: fertility with the phallus and war with the sword. G. Javakhishvili makes the following note about the cult significance of these artifacts: “Small-sized sculptures of people were made, which, by their posture, movement, and attributes imply a participatory activity. They present to us scenes of battle and round dances, playing music, etc.” (12) As Shalva Amiranashvili points out: “Until now, the fact that the posture of all the figures clearly conveys movement has been overlooked. Some of them look like dancers.” (13) Discussing these figures, Lili Gvaramadze notes: “If we consider these figures from the point of view of the specifics of Georgian choreography, in our opinion, the first pair of dancing bronze figures depicts one of the moments of the Khorumi, namely, a stretched-out, half-squatting position, buknura.” (14) This is one of the most characteristic movements in the modern Khorumi.

Based on the comparison of various choreographic, ethnographic, historical, and literary materials, we can reach the conclusion that the warrior deities represented in the shrines, which form the basis for the Khorumi dance and all archaic Georgian dances represented a cosmogonic idea of the universe. The performance contexts of the Khorumi (mainly sacred rituals and sometimes weddings as well), its choreography and expression, along with the step-patterns present in this dance, which are circular (like the sun, a magical sacral sign), multi-level (like a model of the universe), and rectilinear (suggesting interspatial boundaries in horizontal view or a hyperspace tunnel), and the precise, orderly rows of Georgian warriors—all of these are symbolic representations of the harmonious, orderly, earthly world, which confronts the unknown, the otherworldly—chaos. (15) The martial aspect of the dance is also expressed in the confrontation of two opposites represented by the two-row Khorumi form, which culminates in the indispensable victory of the cosmos, good and light, over chaos. Just as depictions of fighting animals, the divine hunt, the defeat of monsters or whales which appeared on archaic artifacts were symbols of a comprehensive cosmogonic idea, so the victory over any enemy who threatened the perfect world of mankind should be understood as a symbol of ancient people’s idea of the universe.

In sum, I think that the Khorumi dance, with its symbolic choreographic patterns created by the performers directly indicates the connection of this dance with the act of creation and the establishment of harmony in the world. In this way, it appears related to rituals like the Murqvamoba, Kviria, and Atengenobi (or atnigenobi), where we see similar choreographic forms and images. Thus, the Khorumi should be considered not only as a stand-alone dance dedicated to a deity, but as an integral part of a complex system, which includes the harmonization of all the necessary conditions of importance for a person’s well-being.

The differences in the interpretation of the meaning of Khorumi can be explained by the distillation of the symbol into a single sign, which denotes the so-called fading of content (i.e. the symbol-sign has lost its original meaning). According to mythology, it was necessary to fight to gain fertility. When the original meaning of the symbol (the deity of fertility) lost its relevance, gradually only the combative content remained, due to Georgia’s history and political situation remained. In the end, only the aspect of fun and games was left. The form, however, remained unchanged, in accordance with the nature of the symbol.

References

- 1.For a description of pieces and performance material, see Avtandil Tataradze, Kartuli khalkhuri tsekva (Georgian folk dance) (Tbilisi: State Folklore Center Editions 2010), 46–72.

- 2.Mari, Niko [Nikolai Marr]. 2015. Shavshetsa da k’larjetshi mogzaurobis dghiurebi (Diaries of a journey to Shavsheti and Klarjeti). Batumi: Shota Rustaveli Batumi State University, 141. (Originally published in 1911 in Russian as Dnevnik poezdki v Shavsheti i Klardzheti.)

- 3.1967. Anabasis, vol. IV, trans. Temuraz Mikeladze. Tbilisi: Metsniereba, 100

- 4.Janelidze, 1948. Kartuli teat’ris khalkhuri sats’q’isebi (The folk beginnings of Georgian theater), vol. I.. Tbilisi: Sakhelgami, 168.

- 5.Gvaramadze, Lili. 1957. Kartuli khalkhuri koreograpia: Dziritadi sak’itkhebi (Georgian folk choreography: Main issues). Tbilisi: Khelovneba, 98–99.

- 6.Gvaramadze, Kartuli khalkhuri koreograpia, 80.

- 7.Chanishvili, 2002. Ts’erilebi koreograpiaze (Letters on choreography). Tbilisi: Tani, 91–92

- 8.Eliade, 1971. The Myth of the Eternal Return or, Cosmos and History, trans. Willard R. Trask. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- 9.Javakhishvili, Ivane. 1990. Kartuli musik’is ist’oriis dziritadi sak’itkhebi (The main issues in the history of Georgian music). Tbilisi: Khelovneba, 211.

- 10.Khidasheli, M. 2002. “Brdzolis k’osmogoniuri k’ontseptsia sakartvelos udzveles sulier k’ult’urashi” (The cosmogonic concept of battle in the ancient spiritual culture of Georgia). Sakartvelos sidzveleni (Antiquities of Georgia) 2: 9–10.

- 11.Phantskhava, Leila and Besarion Maisuradze. “Brinjaos antrop’omorpuli pigurebi shildis samlotsvelodan” (Bronze anthropomorphic figures from Shilda shrine], Journal of the Centre for Archaeological Studies of the Georgian Academy of Sciences. Supplement no. 6 (Essays on the Archaeology of the Neolithic-Bronze Age): 149–150

- 12.Javakhishvili, G. 1984. Antrop’omorpuli p’last’ik’a ts’armartuli khanis sakartveloshi (Anthropomorphic plasticity in pagan Georgia). Tbilisi: Tbilisi University Press, 48–49.

- 13.Amiranashvili, Shalva. 197 Kartuli khelovnebis ist’oria (History of Georgian art). Tbilisi: Khelovneba, 57

- 14.Gvaramadze Lili. 1997. Kartuli satsek’vao polk’lori (Georgian dance folklore) edited by Baia Asieshvili and Otar Tsitsishvili. 2nd ed. Tbilisi.

- 15.For a symbolic description of the forms of Georgian dance patterns, see Ekaterine Geliashvili, Ornament’uli simbolik’a kartul khalkhur koreograpiashi. (Ornamental symbolism in Georgian folk choreography). PhD diss., Shota Rustaveli Theatre and Film Georgia State University, 2014. (link)

Further reading:

1.Davitadze, Emen. 1978. Ach’aruli polk’lori (Ach’aran folklore]). Tbilisi: Sabch’ota sakartvelo. See especially p. 65.

2.Kvirkvaia, Revaz. 2009. “Borjomis kheoba rk’inis parto atvisebis khanashi (dzv.ts’. VIII-VII ss.)” (The Borjomi valley during the Iron Age [8th–7th centuries BCE]). PhD diss., Tbilisi State University. See especially pp. 138–139.

3.Kikvidze, Iazon. 1976. Mits’atmokmedeba da samits’atmokmedo k’ult’i dzvel sakartveloshi. (Agriculture and agricultural Cults in ancient Georgia). Tbilisi: Metsniereba. See especially p. 222.

[i]The the origin of the term gadakhveuli has not been fully studied to date. There are several theories on this subject. Some researchers believe that gadakhveuli should refer to a dance with arms interlocked. Among other points of view, the famous choreographer Enver Khabadze believed that gadakhveuli here should be understood as referring to a “digression” (gadakhveva) from the general rule. In “stage-folk” versions of the gadakhveuli Khorumi (i.e., when performed on its own, not as part of a ballet) the moves performed by the dancers give the impression that they are trampling the enemy with their feet. Thus the majority of scholars agree with this interpretation, rather than the interlocking-arms idea. I discuss the labor-process theory of Rezo Chanishvili later in this article. Among the performers and choreographers who brought the gadakhveuli Khorumi to prominence on stage were Khasan Megrelidze, Enver Khalvashi, and Enver Khabadze.