Georgian Folk Tales (A Brief Overview)

The fairy tale is one of the oldest genres of folklore: it dates back thousands of years and lives on to this day. The term “fairy tale” is often used in the general sense of a “folk tale,” which may include myths, fables, morality lessons, legends, and historical tales. More specifically, however, if one considers the fairy tale a particular genre of folk storytelling, it includes both magical and realistic (or household) tales, as well as animal fables and anecdotes in its subgenres. It should be distinguished from heroic stories and legends, the contents of which are more or less intertwined with historical reality. Among the oral genres, the fairy tale is the most international in its characteristics. Fairy-tale plots spread quickly and widely. In Georgian, the word for “fairy tale” is zghap’ari (adjective form sazghap’ro). Georgia is part of the broader culture of the Caucasus, which for centuries has been situated at the crossroads of Eastern and Western civilizations. Relations with Greco-Roman and Iranian-Arab countries made the Caucasus part of both worlds, which was reflected in various ways in the language and genre of zghap’ari.

Figure 1 . Ts’ikara

Let us now turn to several sub-categories within the Georgian fairy tale tradition. A magical tale has a well-established structure that begins with the hero leaving home, overcoming various obstacles, and finally returning home or becoming a king. The main character of a magical tale is always human, around which other characters gather: people, animals, supernatural beings. In magical tales, we can see the reflection of various mythological and religious worldviews. Not infrequently, remnants of ancient belief systems and characteristics of later historical eras coexist in fairy tales.

The most popular magical characters in Georgian fairy tales are the mother of Devi (the Devi’s are a race of monsters), the dragon, and the firebird. Meanwhile horses, bulls, deer, foxes, and fish make up the typical animal supporting cast. All these characters are secondary to the human at the center of the story. Famous Georgian magical fairy tales (many of them bearing the name of a main character) include “Aspurtsela,” “Irmisa,” “Adikhanjala,” “Ia Khatunisa,” “Shavchit’a Rashi,” “Sulambari and Gulambari,” “The Hunter's Son,” and others.

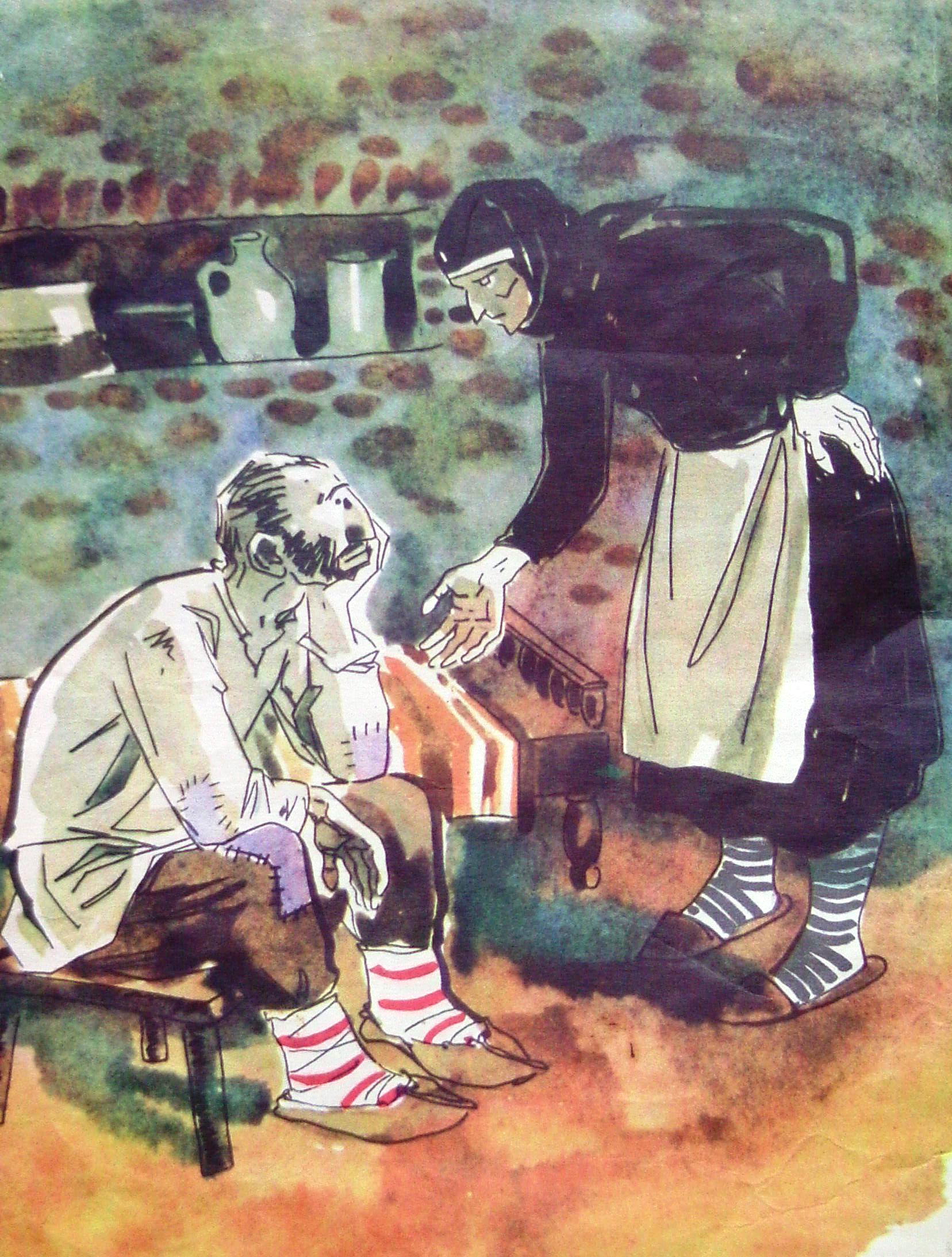

Realistic fairy tales or folk novellas offer the best material for those who are interested in culturological topics. The social life, ethnic, or religious characteristics of particular groups of people are more discernable in this sub-genre of fairy tales than in the magical fairy tales. In these realistic, everyday-life fairy tales, the individuality of the characters is more pronounced. The gallery of characters in these folk novellas is diverse. It is true that they are not literary heroes, but they tend to display different psychological states, as opposed to a magical fairy tale, in which emotions are typically not conveyed. This is one of the main characteristics of folk tales in general. The inner world of the protagonist is expressed through actions, not by the narrator's personal characterization. Realistic fairy tales have a lot in common with anecdotes, making use of humor and satire to depict social class relationships, family relationships, and more.

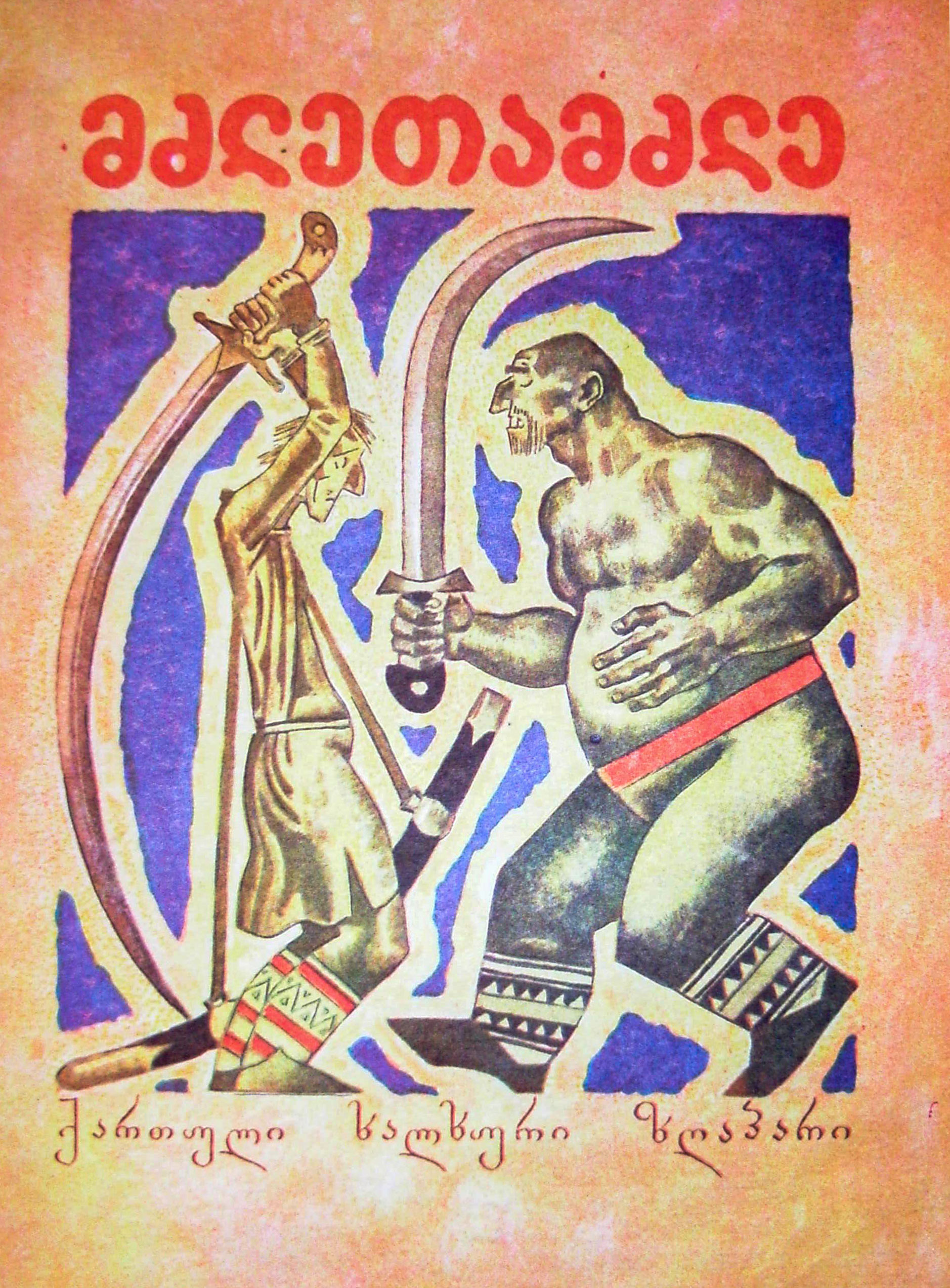

Figure 2. Mdzeltamdzle

Fairy tales of the realistic or “everyday” genre tell us stories that are actually from the realm of possibility, but still somewhat special. The characters here are ordinary, if unusual people, who inhabit a familiar world, one similar to our own. Some well-known examples of household fairy tales and anecdotes are “Much’anakhevara,” “The Hospitable Wife,” “I have smarts, but no money,” “The Goldsmith's wife,” “Uknara,” “Mdzeltamdzle,” and others. Much’anakhevara is an unlucky and clumsy man; Uknara is lazy and stupid; Mdzeltamdzle is handy and lucky; the main character of “I have smarts, but no money” is wise and honest; “The Hospitable Wife” is a religious morality tale about human generosity; “The Goldsmith's Wife” is a cheery tale about a love triangle, in which a young man tunnels into the room of a goldsmith's wife.

Picture 3. Much’anakhevara

The animal epos is considered the most archaic type among the subgenres of the fairy tale. The main characters of these tales are animals; however, they are not allegories of human qualities, the way they are in literary fables. Animal epics are simple narratives and may sometimes contain signs of totemistic representations, that is, a belief in animals as ancestral figures. These texts often contain a poetic component, as in the fairy tale “The Flea and the Ant.” Some are entirely in verse, for example, “Come, let’s see the vineyard.”

Oral genres co-exist side by side, constantly influencing each other. For example, some fairy tales explicitly mention the location of the main action, bringing them closer to legends. One method of classification involves the text’s structure and the kind of ending it has: a magical fairy tale must have a happy ending. There are some texts that talk about miracles, oscillating between the genres of legend and fairy tale. When a fairy tale involves a Christian saint who helps the protagonist—in Georgian fairy tales, it is usually St. George—such texts are usually referred to as legendary tales. Some “everyday” tales can also be called anecdotes. And epics often take the form of magical fairy tales. The abundance of fairytale elements in legends and mythological narratives (and vice versa), as well as the important role of mythology in the plot development of fairy tales, are frequent phenomena in the Georgian oral tradition. Mythical and fairytale elements can be found in almost all epic works.

Figure 4. Devi

Searching for mythical elements in any text, and especially in a fairy tale requires great care. As soon as any motif, character, or element enters a fairy tale, it loses its former function and acquires a new one, sometimes one completely opposite to the original. The plot of the fairy tale itself determines what function the mythical character or element at hand will perform. The best example of this is the character of the horse in magical fairy tales. The coloring, attributes, and supernatural properties of the rashi (an archaic word for horse, akin to “steed”) point to its mythical origin. The horses in fairy tales from all over the world, especially those from Europe and Central Asia, bear certain similarities to each other. The mythical roots of the fairytale rashi are apparent in its nature, which references the natural elements—fire, water, and air, and sometimes all four elements together. There is the flame-breathing rashi, the sea rashi, the winged rashi. In magical fairy tales, the rashi has lost its original, primary function, and the horse acts mainly as a helper.

At the same time, there are fairy tales in which the mythical elements maintain their importance, affecting the development of the plot. This relationship between the fairy tale and myth is most clearly manifested in the final episodes of the story: the fairy tale either ends tragically, or has no ending. Such texts can be conditionally referred to as “mixed-genre.” An example of a mixed-genre text is the mythical fairy tale “Ts’ikara,” which has a sad ending.

Figure 5. Avtandil

Studying fairy tales in Georgia . The “golden age” of collecting Georgian folk tales began in the second half of the nineteenth century. The Society for the Spreading of Literacy among the Georgians and the Historical-Ethnographic Society made the greatest contributions to this undertaking. A number of famous writers, scientists and public figures—among them Akaki Tsereteli, Aleksandre Khakhanashvili, Tedo Razikashvili, Petre Umikashvili, Yakob Gogebashvili, and Ekvtime Takaishvili—played a role in the collection and publication of fairy tales, as well as other pieces of folk literature. A country like Georgia, with its extensive literary tradition, as well as a rich and diverse oral tradition, always remains attractive for researchers and is full of new discoveries. Scholars never lost interest in Georgian, and many important works have been published since the nineteenth century, including foreign-language translations and essays. Research on the subject of Georgian folk tales in the Georgian scholarly space covers various cultural and historical aspects: genesis, thematics, social function, the search for mythological remnants, morphological-semantic analysis, socio-cultural aspects, and others. Yet there are still many outstanding questions requiring further research.

References

- 1.Gogiashvili, Elene, ed. 2019. Aghmosavleti da dasavleti kartul khalkhur zghap’rebshi: Zep’iri da lit’erat’uruli t’raditsiebi (East and west in Georgian folk tales: Oral and literary traditions). Tbilisi: Georgian National Center of Manuscripts.

- 2.Kiknadze, Zurab. 2007. Kartuli Polklori (Georgian folklore). Tbilisi: Tbilisi University Press.

- 3.Chikovani, Mikheil, ed. 1960. Kartuli khalkhuri p’oet’uri shemokmedeba (Georgian Folk Poetry). Tbilisi: Georgian SSR Academy of Sciences.

- 4.Kurdovanidze, Teimuraz. 2002. Kartuli zghap’ari (The Georgian fairy tale). Tbilisi: Merani.

- 5.Ghlonti, Aleksandre. 1963. Kartuli khalkhuri novela. (The Georgian folk novella). Tbilisi: Sabch’ota Sakartvelo.

- 6.Chikovani, Mikheil. 1946. Kartuli polk’lori (Georgian folklore). Tbilisi: Sakhelgami.

- 7.Choloqashvili, Rusudan. 2004. Udzvelesi rts’mena-ts’armodgenebis k’vali zghap’rul ep’osshi (Traces of ancient beliefs and perceptions in the fairy tale epic). Tbilisi: .

- 8.Wardrop, Marjorie, trans. 1894. Georgian Folk Tales. London: David Nutt.

Image Credits

Cover: artist Tengiz Mirzashvili.

“Iq’o da ara iq’o ra” (“Once upon a time”). Kartuli khalkhuri zghap’rebi (Georgian folk tales), edited by Sulkhan Ketelauri, 1977.

Figure 1. Artist Jemal Zenaishvili.

Kartuli khalkhuri zghap’rebi (Georgian folk tales), edited by Alexander Ghlonti, 1992.

Figure 2. Artist Dimitri Khahutashvili.

“Mdzeltamdzle.” Kartuli khalkhuri zghap’rebi. (Georgian folk tales), 1980.

Figure 3. Artist Dimitri Khahutashvili.

“Much’anakhevara.” Kartuli khalkhuri zghap’rebi (Georgian folk tales), 1963.

Figure 4. Artist Tengiz Mirzashvili.

“Iq’o da ara iq’o ra” (“Once upon a time”). Kartuli khalkhuri zghap’rebi (Georgian folk tales),edited by Sulkhan Ketelauri, 1977.

Figure 5. Artist Irakli Toidze.

Shota Rustaveli, Vepkhist’q’aosani (The Knight in the Panther’s Skin), 1937.