May Day: The Soviet Ghost of Labour Day

May 1st, International Workers' Day, was one of the key holidays in the Soviet Union. Although the holiday was in its essence a celebration of the working class, in the Soviet Union it did not truly represent the ideals of the workers for whom May Day originally united the international proletariat. Instead, the USSR was a militarized state that hid behind the faces of the workers and the ideas of Marx, through the lenses of Leninist, Stalinist, and other Soviet ideologists.

In general, events, facts, and their subsequent interpretations do not always align. People receive information, reflect on it, and adjust it to their own interpretation. Thus, it is important to understand the context in which a particular holiday gains its significance.[1] The historian Eric Hobsbawm is known for coining the term ‘invented tradition.’[2] He explored how traditions in modern times depend on their social, political, and ideological context for their existence.[3]

The practice of celebrating May Day in post-socialist Georgia exists in two forms: as a Soviet relic (a tradition carried over from past regimes) and as the globally recognized International Workers' Day.

For those who lived through the Soviet era, May Day is more closely associated with the sentiments of that time than with a day dedicated to the struggle for workers' rights and welfare in today’s globalized, neo-liberal, and deregulated market economies. In Georgia, May Day has become a focal point for leftist civil society, particularly regarding workers' rights. The significance of Labour Day in contemporary Georgia still falls short of the scale and content of Soviet-era celebrations, largely due to the collapse of the Soviet system. From this perspective, the European Union is attracting Georgian workers to its market more rapidly than is Georgia’s developing economy and production infrastructure. In this context, it is worth considering the practice of celebrating May Day as a Soviet sentiment which, in light of the experiences over more than three decades since Georgia's independence, is now perceived differently by today’s citizens.

When discussing context, it's important to consider a key aspect of Soviet ideology: Soviet secular politics, also known as militant/fighting atheism. This was an idea that opposed religion but at the same time established a religious practice based on a new proletarian dictatorship.[4] An example of this was the adaptation of religious terminology and symbols to fit Soviet ideals. For instance, the Cathedral in the city of Poti was transformed into a theater with a statue of Lenin. Party congresses were held inside this theater, and parades, such as the May Day marches, took place outside. These processions, with their ritualistic repetition and specific content, infused the holiday with a Soviet character, turning it into one of the symbolic tools of the workers' dictatorship. Thus, while traditional holidays were once centred around the veneration of saints, May Day established a new foundation for a new ideology.

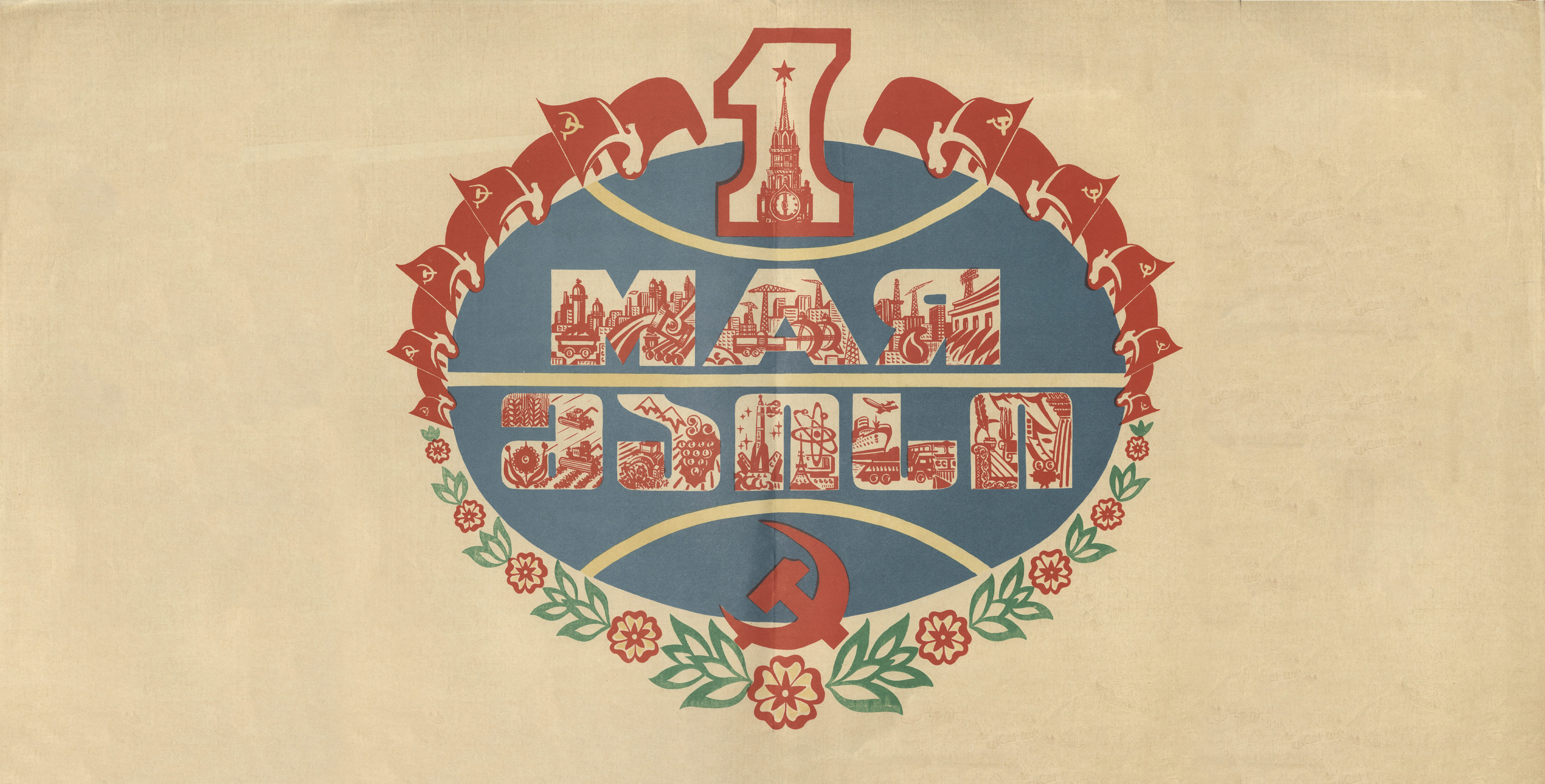

Gunzadze, G. (1981). May 1st. Tbilisi, Publishing House of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Georgia. Collection of the National Parliamentary Library of Georgia. https://dspace.nplg.gov.ge/handle/1234/400661

The celebration of May Day held particular significance for the Communist Party. Notably, issue number 49 of the Communist newspaper, dated May 1, 1921, features a headline that reads:

‘Happy Labour Day, Happy May Day! Long live the international proletariat, long live the Third Communist International! Long live the international revolution and its vanguard—Soviet Russia! Long live Soviet Georgia! Long live Communism!’

This issue highlights the glorification of the international proletariat and its significance for Soviet Georgia, where workers were no longer an external force opposing the state but had become the state itself and its protector. This slogan was a cornerstone of Soviet ideology, serving as the guiding force behind the political order throughout the regime's existence, ultimately creating a militarized workers' state.

May 1st being known as Labour Day has its roots in the events of 1886, when a May Day protest in Chicago advocating for workers' rights and better working conditions (specifically an 8-hour working day) resulted in fatalities. This day subsequently became recognized as Labour Day, and its celebration became an annual tradition. In addition, May 1st as May Day is an ancient holiday that traces its roots back to ancient Rome, where it was a celebration of spring. The merging of these two historical elements led to the creation of Labour Day as it is known today, marked by workers' demonstrations in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Globally, the day is celebrated as a tribute to the collective resilience of workers. In the United States, Labour Day is observed on the first Monday of September, but May Day remains a day for protests and discussions around the needs of the working class.[5]

Before the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, May Day was celebrated as an unofficial holiday in the Russian Empire. In 1918, it was declared a public holiday in Soviet Russia. Since 1992, it has been known as the Holiday of Spring and Labour. Throughout the Soviet Union, the day symbolised class struggle and resistance.[6]

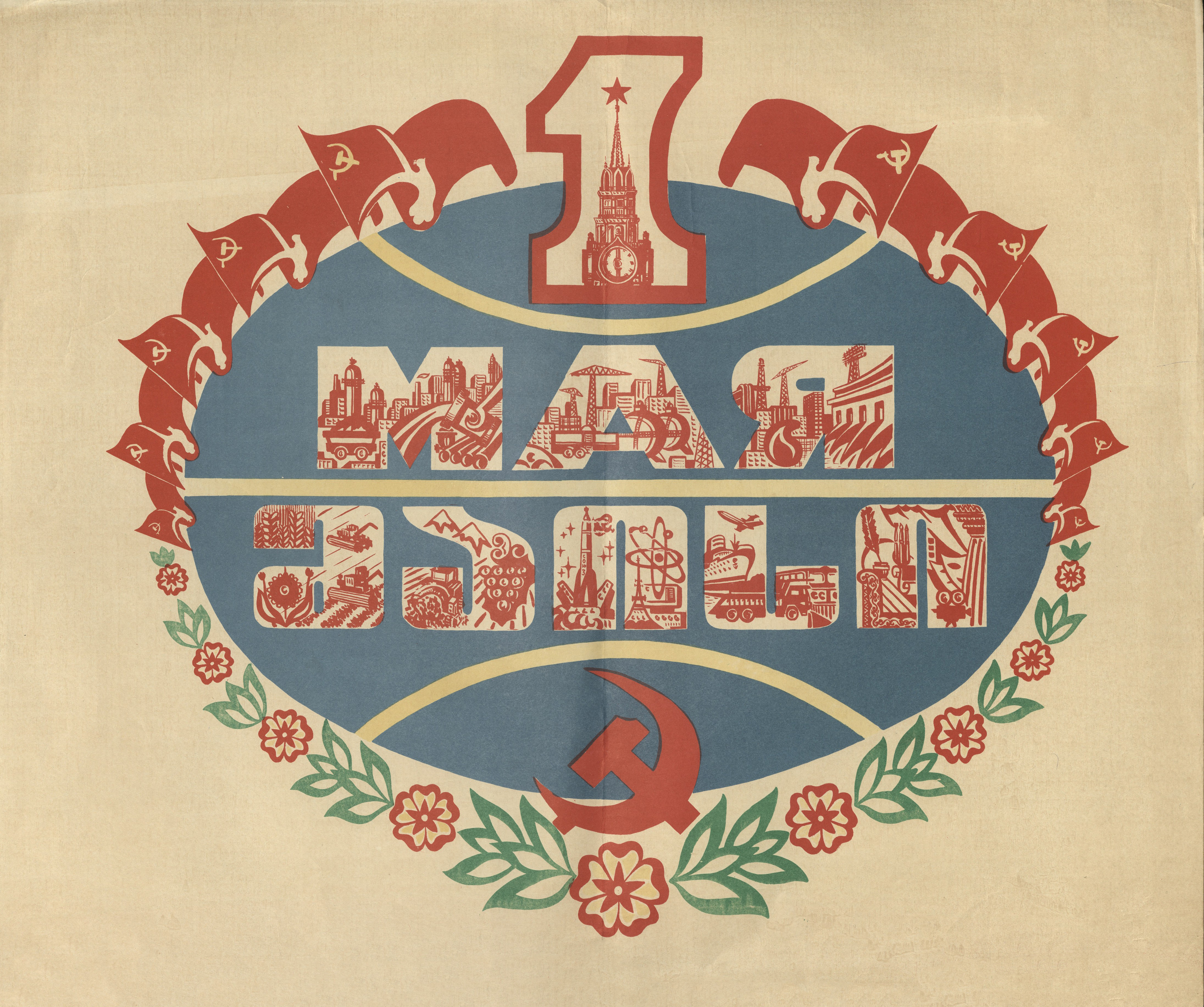

Varkvadze, O. (1958). May 1st is International Workers' Day. Poster. Publishing House "Soviet Georgia," Tbilisi. Collection of the National Parliamentary Library of Georgia. https://dspace.nplg.gov.ge/handle/1234/302792

The form and content of May Day celebrations evoke strong associations for people now aged 50-70. During the Soviet era, the celebration of this holiday was linked to childhood and the school years.

When discussing holidays, informants in Georgia focused on religious rituals and practices that were absent from the public sphere during the Soviet era and remained part of family traditions.[7] When asked which holidays they celebrated during the Soviet period, their emphasis was placed on the observance of religious rituals, which were publicly forbidden but celebrated within the family, followed by a question about the observance of public holidays (including May Day). If we consider this nuance, it becomes clear that, despite the Communist Party's efforts, the practice of Soviet public rituals could not surpass religious rituals and holidays (such as Easter and Christmas), whose centuries-old traditions persisted. Even though these holidays were driven out of the public sphere, their forms were preserved in popular life and their significance ultimately outshone the alternative holidays promoted by the Party (such as May Day and November 7).

One of my informants, Mariam, was 53 years old. Speaking about the first of May, she mentioned that the school used to prepare especially for this day. They set up various displays glorifying the Communist Party and prepared for the parade. She said:

‘I remember building a wooden structure in the shape of a star, thus starting the preparations. We had such a structure in the main square. The young people standing around it were wearing uniforms of different colors. We held hands around this star and walked out. Both local people and members of government and party delegations took part in the day's celebrations. High school students traveled to the parade in decorated cars, holding flags and posters glorifying the Communist Party.’

Mariam did not understand the meaning of the holiday; for her, May Day during the Soviet period created a festive mood without any ideological context. Memories of school and childhood, evoking feelings and experiences of the past, were more important to her than the ideological context.

For Mariam, the celebration of the day also involved a public display of family relations after the parade. She remembered that her mother also participated in the processions, representing the wine factory. She recalled that adults were trained in the same way as schoolchildren. They were also grouped by height and gender, and they marched like that. Once the parade ended, the real celebration was about to begin for Mariam. Her mother had specially prepared her for the day. She bought Mariam new clothes, which she wore after the march. Dressed in her new clothes, Mariam took her mother for a photo shoot, after which they went to a café. Spending time with her mother in the café that day was a special feeling, one that for her surpassed any ideological significance, because, as she said, she did not understand what she was doing. Even when interviewed, she did not know exactly what was being celebrated on the first of May.

Mariam graduated from school in 1988, and since then she no longer celebrates the first of May. People no longer have the special festive mood on this day that they once had. She also does not know if the day was even celebrated after 1988. In her words:

“As the Soviet Union collapsed, this day lost its meaning; neither I nor anyone else was happy. Then there was war, adversity, and nobody was interested in this day. The first of May was a special day, as was the seventh of November when we marched. The euphoria of celebrating both days is a thing of the past; I can't say that celebrating either of them is the same as remembering that day.”

The next informant, Nino, was 56 years old. Her views on the May Day holiday were similar to those of the previous informant. However, for Nino, May Day was solely associated with a carefully planned parade, where every stage (from the rehearsals to the celebration itself) was strictly controlled. When I asked her to describe the practice of celebrating May Day in a few phrases, she exclaimed: “Hooray, Hooray, Hooray, long live the Soviet Union, long live May Day!”

Nino focused on the dress code of the students in the parade. She explained that they were brought to school in the same uniforms. The girls wore brown dresses and white aprons. May Day was special to her because it was a holiday and there were no classes. They were taken to the parade on open-backed trucks called k'ruzao, which were driven through the city center in formation. She continued:

‘We were taken and divided into columns. We were divided by schools. Different schools had different columns. We would arrive and march in the parade.’

Nino said that the pioneers wore red neckerchiefs around their necks during the parade.

‘It wasn’t allowed not to wear it. The boys wore white shirts, suits, and trousers that didn’t let the air in. They would check how well we were dressed and then let us go. A pioneer was a distinguished student. We were accepted into the ranks of the Pioneers, we took an oath and passed an exam. If you were accepted as a pioneer, you were given a red neckerchief and you had to wear it; it was a source of pride. There was a separate place in the column for pioneers. If you became a member of the Young Communist League after the eighth grade, you received a small badge that you had to wear. During the parade, there was a separate place for them in the column. The convoy was organized as follows: fifth-grade pioneers, sixth-grade, seventh-grade, then eighth-grade Young Communists, and finally tenth-grade. After that, the rest of the students stood behind. There were competitions between the schools to see who would do better and lead the march, and the winning school would be thanked by the government, given certificates, and so on.’

Like the previous informant, Nino did not understand why May Day was celebrated. In her words:

‘I don't know why we celebrated May Day. It was forced—nobody wanted it. If you’re going to lie, at least you should know why you're doing it. In my family, we didn’t approach this holiday with any special mood, as if May Day was coming soon and we had to prepare for it... The school prepared for it more than the family did. It was an institutional holiday, not a family one. As far as I know, May Day is a Soviet holiday. It didn’t bring any joy or abundance back then, and if it were celebrated now, this country would be ruined.’

Another informant, Vano (68 years old), to whom I drew attention to the ideological content of this day, said that this day was associated with a parade and march. Unlike the previous informants, he knew what May Day was, although he didn’t really understand its meaning, as was evident from the sentence he uttered: 'The government organized May Day. As far as I knew, it was some kind of working day, an international day,' and he continues, 'May Day was introduced by a communist woman, or was it the eighth of March? The first of May—I don’t remember exactly how, but it was international. It was a forced day anyway, people were indoctrinated to go out on that day. Allegedly, on this day, workers were glorified. It was declared International Workers' Day, and everyone was supposed to show respect. The procession also had an audience. People stood on the side of the roads, behind the columns, holding slogans and applauding. On this day, they pretended to sympathise with the workers, but the government didn’t care about international politics; they were pursuing their own interests.’

Eliadze, D. (owner) (1982). May 1st 1982 demonstration, group photo. Collection of the National Parliamentary Library of Georgia. https://dspace.nplg.gov.ge/handle/1234/110151

From the interviews, features of the manifestation of May Day celebrations and views related to them are revealed. According to the informants, it can be said that their interpretations of May Day reflect the ghost of the Soviet era, preserved in the memories of those who lived during that time. These memories show that a significant portion of Soviet citizens did not understand either the rights of workers or the specific purpose of celebrating International Workers' Day and its connection to forms of self-expression. For them, the day was more about the formal aspects of its celebration and their personal emotional attitudes, rather than the ideals of workers and the sense of belonging to the working class that Soviet ideology sought to instil in citizens.

[1] Komakhidze, Boris. “The Visibility of Georgian Hagia Sophia: Urban Religious Transformation in Poti, Georgia.” Urbanities 12 (1): 76–92, 2022. https://www.anthrojournal-urbanities.com/vol-12-no-1-may-2022/

[2] Hobsbawm, Eric. Introduction: The Invention of Tradition. in Hobsbawm, Eric & Ranger, Terence (eds.). The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983, 1-14 .

[3] Komakhidze, Boris. Pazisis Urbanuli Khilvadoba: Mekhiserebis Transpormatsia Kalak Potshi. Masalebi Sakartvelos Ethnograpiistvis III (29) (Urban Visibility of Pazisi: Transformation of Memory in the City of Poti. Materials for the Ethnography of Georgia III (29)), 2022: 133-155

[4] Pelkmans, Mathijs. Introduction: post-Soviet space and the unexpected turns of religious life. In M. Pelkmans (ed.), Conversion After Socialism: Disruptions, Modernisms and Technologies of Faith in the Former Soviet Union. Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2009.

[5] Leinebaugh, Peter. The Incomplete, True, Authentic, and Wonderful History of May Day. PM Press/Spectre, 2016.

[6] Van Ree, Erik. Stalinist ritual and belief system: Reflections on "political religion". Politics, Religion and Ideology, 17 (2-3), 2016, 143-161. https://doi.org/10.1080/21567689.2016.1187600

[7] Dragadze, Tamara. The domestication of religion under Soviet Communism. In C. M. Hann (ed.), Socialism: Ideals, Ideologies, and Local Practice. London: Routledge, 1993.