George Balanchine in Guria

Each photo contains an interesting story. Once you have done research to verify events and identify the people depicted, a photo can bring to life many historical details. The photo itself might have its own history, as well, as in the ones shown here, which date to the first visit of George Balanchine, the brilliant American choreographer of Georgian origin, to Georgia.

In 1917, the Georgian composer Meliton Balanchivadze, then living in Petrograd, returned to Georgia with his youngest son Andria, leaving his older son Giorgi (later George) and his daughter Tamar in Russia. Soon afterward, the the revolutionstook place. George, by then an up-and-coming dancer and choreographer, left the Soviet Union in 1924, before the communist authorities had enough time on their hands to turn to the arts. He went on tour to Europe with a small group of friends, and despite the strict demands of the Soviet government, he didn’t come back. When he finally returned to the USSR, he and his brother Andria met for the first time in forty-five years. Mr. B.—as Balanchine is known in the ballet world—had never been to Georgia before.[1] He visited his homeland and his long-lost brother at the same time.

This reunion took place in 1962. Balanchine visited Tbilisi with his already well-known ballet company, New York City Ballet, and held performances at the Tbilisi Opera House.

The Soviet government created an itinerary for the choreographer’s time in Georgia, which started in Western Georgia with a visit to Kutaisi. Mr. B was not brought to this city by accident. At the Mtsvaneqvavila cemetery, he laid flowers at the grave of his father, Meliton, in the company of his brother Andria, their half-brother Apolon—a former archdeacon and chanter who endured significant persecution from the authorities—and members of the city’s musical society. Balanchine was also shown the historical-ethnographic museum and the Gelati monastery complex.

In an interview with Arabesque magazine, historian Zurab Javakhadze, who was part of the accompanying group, recalled this meeting:

Entering the main Gelati monastery and looking at the icons, Balanchine kneeled down and I noticed tears in his eyes. “I have been to many places, but nowhere have I seen such painting,” he said. [...] He was interested in everything. In Gelati, he observed the ornaments for a long time. Then he began to make a note in Russian in the visitors’ book: “Приятно было очень это место. Горжусь, что я имеретинец, Дж. Баланчин” [This place was very pleasant. I am proud to be an Imeretian. G. Balanchine], though he wrote “имеретинец” with an “э.” I told him that the name of this region was not Emereti, but Imereti.[2]

It is unknown whether George Balanchine may have requested to visit his ancestral village, Banoja, in the Tskaltubo district, the very village the young Meliton Balanchivadze left in 1889 to attend the St. Petersburg Conservatory. In any event, the Soviet authorities did not include it in Balanchine’s itinerary. At one time, the Banoja church was decorated with an inscription indicating that it was built by Anton Balanchivadze, George Balanchivadze’s grandfather.

Guria, however—specifically the Ozurgeti district then known as Makharadze—was in the travel plan, though the exact reason for its inclusion is not known. It is a fact, in any event, that one day spent in Guria left an amazing impression on Balanchine.

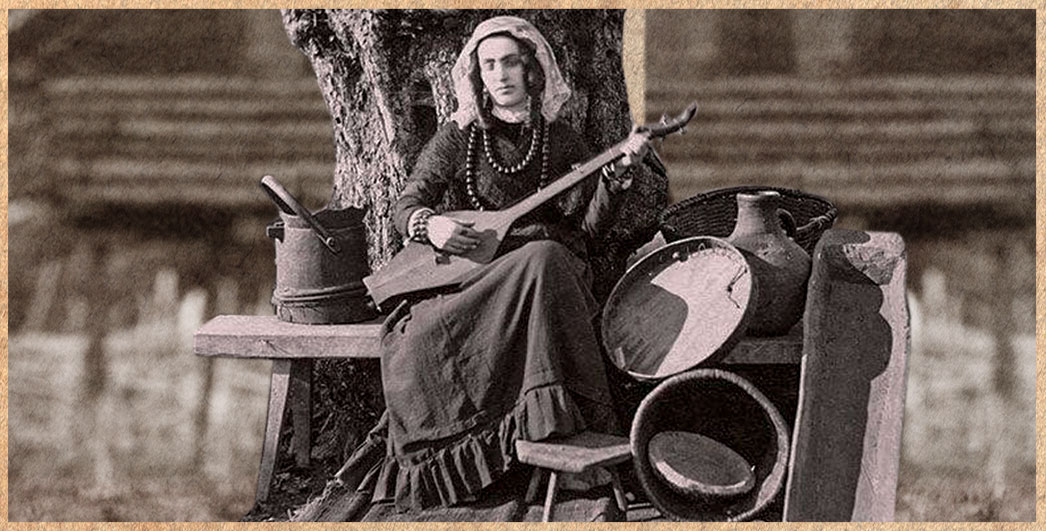

George Balanchine traveled to Makharadze with his brother Andria. The meeting took place at the Isabella restaurant, which sadly no longer stands: in the 1980s this space was dedicated to the glorification of the so-called “military activity” of Leonid Brezhnev, the leader of the Soviet Union, whose behavior had become quite erratic by that time. The beautiful restaurant building was demolished and replaced by a Museum of Glory in Battle of the 18th Army. (Today, the building houses a Museum of Local Lore and a Folklore Center.) One of the dancers present in 1962, who specially performed the Khorumi dance for Balanchine was Avtandil Natsvladze. In a conversation with the author, he recalled, “Balanchine himself wanted to see our dance. He was making notes about each step. He himself sat down among us and learned the movements that way. Our conversation went on for two hours.”[3]

Fortunately, the camera captured this historical meeting. In the hall, together with Balanchine, his companions are watching the performance of dancers from Ozurgeti.[4]

Balanchine could not hide his excitement, the participants of the meeting recalled. This is clearly expressed in the interview George Balanchine gave to the Soviet Georgian press before leaving Georgia:

I also visited Guria. I will never forget the special warmth with which the hospitable people of Makharadze welcomed me. Their hospitality knows no limits, but the most precious things I was treated to at the supra were the Gurian songs and dances.

K’rimanch’uli [yodeling] left a deep impression on me. How profound must the people’s culture be to create such extraordinary polyphony! It's really amazing! But still, for me, as a choreographer, the folk dances really made an unforgettable impression. My eyes were fixed on them, so that I didn't miss a single movement, a single gesture, a single pas.

I am sure that when youth here dress in national clothes, they respect themselves and their national values more; I think this is where the character of the dance comes from: proud, daring, decisive...

I have already said, and I want to repeat now, that if these dances are beautiful flowers, then I saw a wonderful bouquet of them in Makharadze. Can anyone get bored of enjoying beautiful flowers?! Unfortunately, I didn't have much time, otherwise I would have spent hours watching these fascinating dances.[5]

When Balanchine mentions the supra in this interview, this is what is is captured in the third photo. The picture is also memorable because we also can see the famous choirmaster and unique k’rimanch’uli performer Misha Shavishvili, along with the first generation of singers from his famous ensemble Shvidkatsa. Nearly everyone in the picture can be identified.[6]

George Balanchine came back to Georgia a second time, ten years later, in 1972. Georgian polyphony was not neglected by him this time either. In one interview, he also mentioned the evaluation of Igor Stravinsky.[7]

Just today I was given the notation of some pieces of Georgian three-part music. It is very interesting. I think a lot about Georgian folk polyphony. My friend, the great composer Igor Stravinsky, praised it highly. “Georgian polyphony is a masterpiece that has no equal,” he wrote. You may have noticed that my ballets have a polyphonic foundation. This is another reason why I want to stage a performance to Georgian music in the near future.[8]

Unfortunately, this idea of Balanchine’s remained unrealized.

[1] This nickname gives the title of Jennifer Homans’s recent biography, Mr. B: George Balanchine’s 20th Century (New York: Random House, 2023). On the 1962 USSR tour, see Jennifer Homans, “George Balanchine’s Soviet Reckoning,” The New Yorker, September 5, 2022.

[2] Irma Tcholadze, “Meetings in Georgia,” Arabesque, no. 23 (2014/1): 39, English translation modified.

[3] “Balanchini sts’avlobs ‘khorums’” (Balanchine studies the Khorumi), Arabeqsue, no. 1 (2006/1): 10.

[4] In a 2013 TV documentary, the director Oliko Zghenti interviewed the participants of this meeting. See George Balanchine in Guria (film in Georgian).

[5] “Jorj balanchini: bednieri var, rom vnakhe akhali sakartvelo” (George Balanchine: I’m happy that I saw the new Georgia), K’omunist’i, November 29, 1962 (No. 280), p. 4. Reprinted, with English translation, as “George Balanchine: Happy to See Georgia,” in the journal Arabesque, no. 23 (2014/1): 41–42.

[6] Balanchine is sitting on the right. His brother, Andria Balanchivadze, is to his left, and Mrs.Natasha Molostwoff, who worked at the New York City Ballet school and accompanied Mr. B. during his trip to the USSR, is to his right. The tamada or toastmaster was Kukuri Anthelidze (standing), then the head of the Cultural Services. Then, from the left, the members of ensemble Shvidkatsa, sitting: Teimuraz (Teziko) Kiliptari, Aleksandre Gogava, Misha Shavishvili (Shvidkatsa’s leader), Zaur Bolkvadze (probably), Nodar Kartsivadze, Amiran Babilodze, and finally Giorgi Salukvadze (with a cigarette), famous choir master, singer, and choreographer. It is possible that some details here require further verification. Photo provided by Manuchar Mameishvili.

[7] See Brian Fairley, “What did Stravinsky Really Say about Georgian Music?”. Georgian Folklore, no. 3 (2023).

[8] S. Begiashvili. “Jorj balanchini: musik’a tsek’vaa, tsek’va–musik’a” (George Balanchine: Music is dance, dance is music.” K’omunist’i, October 8, 1972 (No. 237), p. 4. Reprinted in abridged form, with English translation, in the journal Arabesque, no. 23 (2014/1): 44.