The Role of Chichilaki in New Year’s Celebrations

All the world's a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts…

William Shakespeare

Georgians, like many other people, celebrate the New Year in January[1] and mark the departure of the old year and the coming of the new year with a holiday, which over time acquired the form of a “New Year’s performance.” During the holidays, everyday life resembles a ritual, and in the mythologized environment created by society, objects and people are symbolically transformed into something other, different from everyday experience.

In Georgian traditions (as well as those of many other cultures), the magic of the first day always received special attention; it was important how the first day—of the week, month, or year—began. Therefore, who would be the first to visit the family in the new year and what this person would bring had great significance. As such, this first visitor—mekvle in Georgian, “first foot”[2] (or “trailblazer”) or “trailblazer”—was considered to be the main link of communication between the outer and inner worlds, the microcosm and macrocosm. The mekvle, whose lucky feet were to bring prosperity to the family, became an allegory for a higher power. The New Year’s greeting formula is also an expression of this idea: “I step inside, may God bless you, my feet are the tracks of an angel.”

Traditionally, the main protagonists of the New Year's mytho-ritual scenario were divided into two groups, between the inner and outer worlds, and this performance was renewed and repeated every year. The mekvle, who came from the outside, as a stranger, personified a higher power, specifically St. Basil, whose feast-day is January 1. One of their duties was to bring different kinds of goods for each family member. (1)

Selected by vote, the mekvle made special preparations to fulfill this role: on New Year’s Eve, they would go to the forest to bring a branch of a nut tree (a symbol of fertility in the Georgian tradition), which was used to make the sacred New Year's tree, the Chichilaki. (see Fig. 1).

According to ethnographic descriptions, the mekvle would heat a stick of walnut wood over a fire at their home and whittle it so that the shavings would hang down from it in coils. Two wooden crosses would then be fixed horizontally onto the stick, one on the bottom and the other on the top. A braided wreath, decorated with ivy leaves, red hawthorn berries, holly, dark blue ivy berries, mistletoe branches, other evergreen plants and pomegranates, and topped with ritual bread—bokeli—was placed around the tree, as a symbol of fertility. (2) Apple-sized dough balls, called kvinchili would hang down from the dry ends of the wreath, along with thrushes, plucked of their feathers, with only tails and wings intact. (Sometimes only a bird’s tail was hung, as a reference to songbirds, known as siris kudi or “sparrow’s tail.”) These objects served as markers of the heavenly world and symbols of benevolent spiritual beings. Sometimes the tree would be decorated with silver coins, colorful ribbons, candies, and jewelry. According to traditional interpretations, this sacred tree, the Chichilaki, is the Georgian variety of the tree of life. (3) It was also called “Basil’s beard.”

From another perspective, Chichilaki can be connected to the sun. The ritual bread on top of its “beard,” in this particular case, is the sun itself, from which the coils—the rays of the sun—emanate. A Chichilaki, with its celestial markers (cockerels, thrushes or their tails), points not only to the sky, but also to the sun, the source and center of light and warmth. In many traditions, the sun is directly associated with the tree and is perceived as the “fruit” of the tree. The Georgian term for the solstice, mzebudoba (mze “sun” + bude “nest”), is interesting from this point of view, as it refers to the astronomical position of the sun in winter and summer and precisely denotes the period, according to folk beliefs, when the sun rests in its nest. And the nest itself is, naturally, located on a tree.

Thus the Chichilaki may be symbolically connected to the idea of fertility, or it can allude to the heavenly world through celestial symbols, or could even be seen as a completely solar symbol.” The wavy lines of the Chichilaki shavings also have a connection to water. Hence, the shavings on the Chichilaki can be seen as wavy rays, signifying either heat or lightning, the latter understood as the celestial fire and rain which fertilize the earth. Again, the aspect of fertility is dominant in these signs. As Chichilaki was sometimes called “Basil’s beard,” it can also be perceived as a vegetative symbol of St. Basil, or a tree, a dwelling-place for the sun. Therefore, Chichilaki, as a multivalent symbol, with its accented celestial markers referred not only to the sky, but also the sun, the source and center of light and warmth. From a cosmological perspective, the Chichilaki can be viewed as the axis mundi of the universe, which at the same time has fiery and radiant characteristics. In this sense, Chichilaki also has the connotation of the “tree of light.” (1)

The mekvle, who was often called “Basila,” held a wooden bowl, on which the symbols of fertility and prosperity were placed. These included ritual breads (little, raisin-eyed dough-men, also called basila, the number of which corresponded to the number of men in the family); the ritual tree (Chichilaki or Basil’s beard); as well as wine, honey, the boiled head of a sacrificial pig, etc. With these ritual objects and symbols, people tried to establish communication with the sacred world. At dawn, the mekvle (in some cases understood as a personification as St. Basil), covered in symbols of fertility, came to the house door. Only after saying the blessing three times and describing all the good things brought along, the door would be opened and the mekvle would enter the house with the right foot (a guarantee of success for all activities) and bless the family with the following words: “I step inside, may God bless you, my feet are the tracks of an angel.” This greeting once again confirms that the mekvle was the incarnation of a benevolent, holy being who was supposed to bring prosperity to the family for the coming year.

Because the ritual objects, symbols, and actions of the celebration include both canonical Christian elements and folk ritual traditions saturated with cosmological symbolism, they suggest an origin not in paganism but in popular interpretations of Byzantine non-canonical culture.

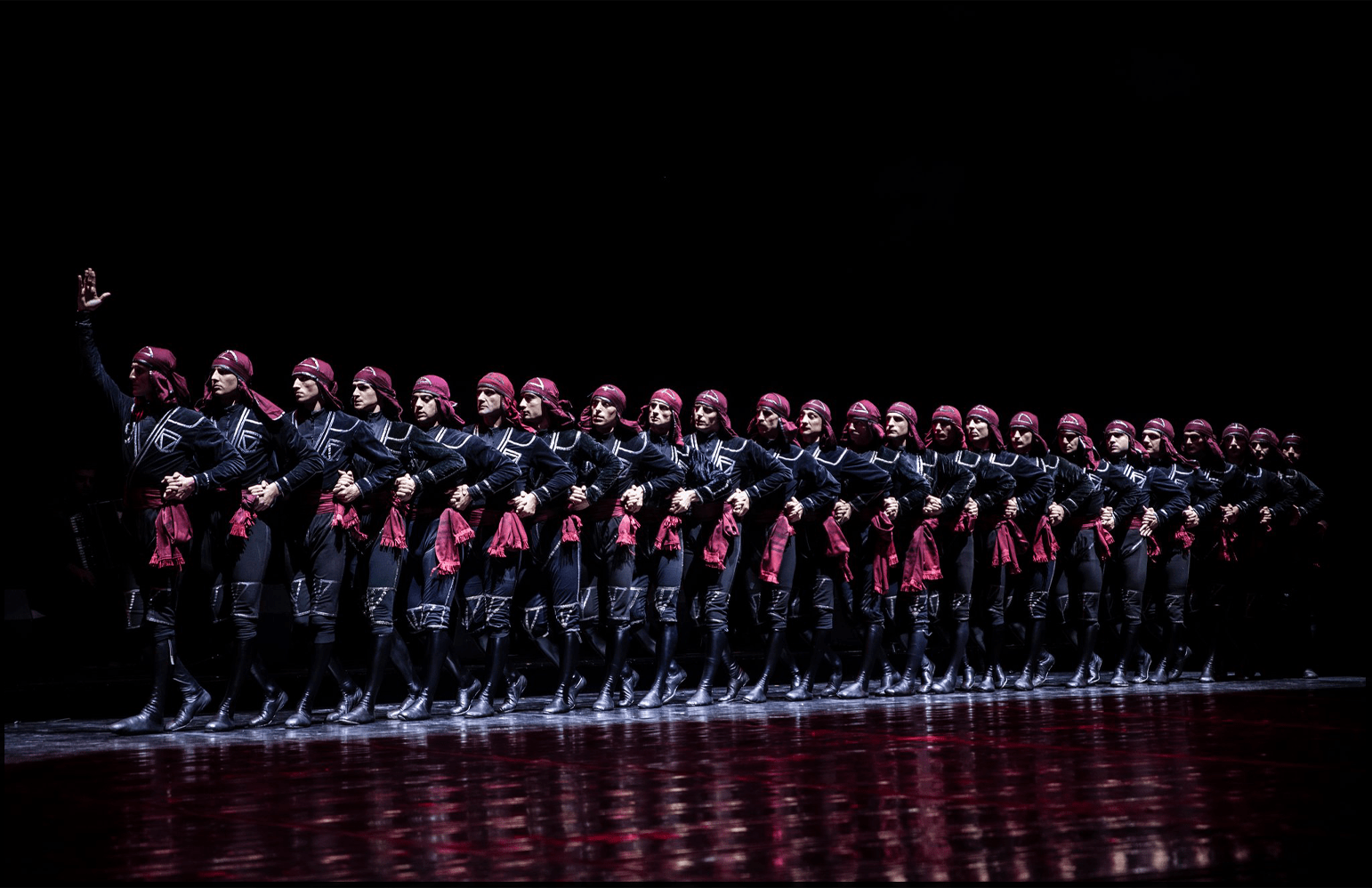

Chichilaki, an integral element of New Year’s Eve celebrations, lost its original meaning and functions in an urban environment. The horizontal Chichilaki cross, on which the fertility-bringing ritual bread was supposed to be placed, took the form of a vertically-erected Christian cross, changing from a symbol of fertility into a New Year’s ornament stripped of its original significance. It now has a role and significance akin to a Georgian “Christmas tree.” A striking example of this can regularly be seen at the Presidential Palace, decorated with chichilakis (see Fig. 2).

Bibliography :

- 1.Abakelia, Nino. 2017. Udzvelesi k’osmologiuri k’ontsep’t’ebi da arkauli religiuri simboloebi kartvelta k’ult’urul mekhsierebashi (Ancient cosmological concepts and archaic religious symbols in Georgian cultural memory). Tbilisi: Ilia State University, 112–141.

- 2.Bardavelidze, Vera. 2006 (1941). Kartvelta udzvelesi sarts’munoebis ist’oriidan (ghvtaeba barbar-babar) (From the history of the ancient beliefs of the Georgians [deities of Barbar-Babar]). Tbilisi: Caucasus House, 71–83

- 3.Bardavelidze, Vera. 2015 (1957). Drevneishie religioznye verovaniia i obriadovoe graficheskoe iskusstvo gruzinskikh plemen (Ancient religious beliefs and ritual graphic art of Georgian tribes). Moscow: Vostochnaia Literatura RAN, 109-113.

- 4.Abakelia, Nino, Ketevan Alaverdashvili, and Nino Gambashidze. 1991. Kartuli khalkhuri dgheobata k’alendari (Calendar of Georgian folk celebrations). Tbilisi: Krialosani, 28–47.

[1]At various times in Georgian history, other months have been considered the start of the year, including March, August, or September. The January calendar means the year is counted from the month of January. This expression is used in Georgian special literature, because due to the endless reforms of the calendar, the countdown of the new year in Georgian realities began either from March, or from August, or from September, until they began to count the year from January. And the March calendar, August calendar, etc. are used to indicate which month the year begins.

[2] First guest of the New Year.