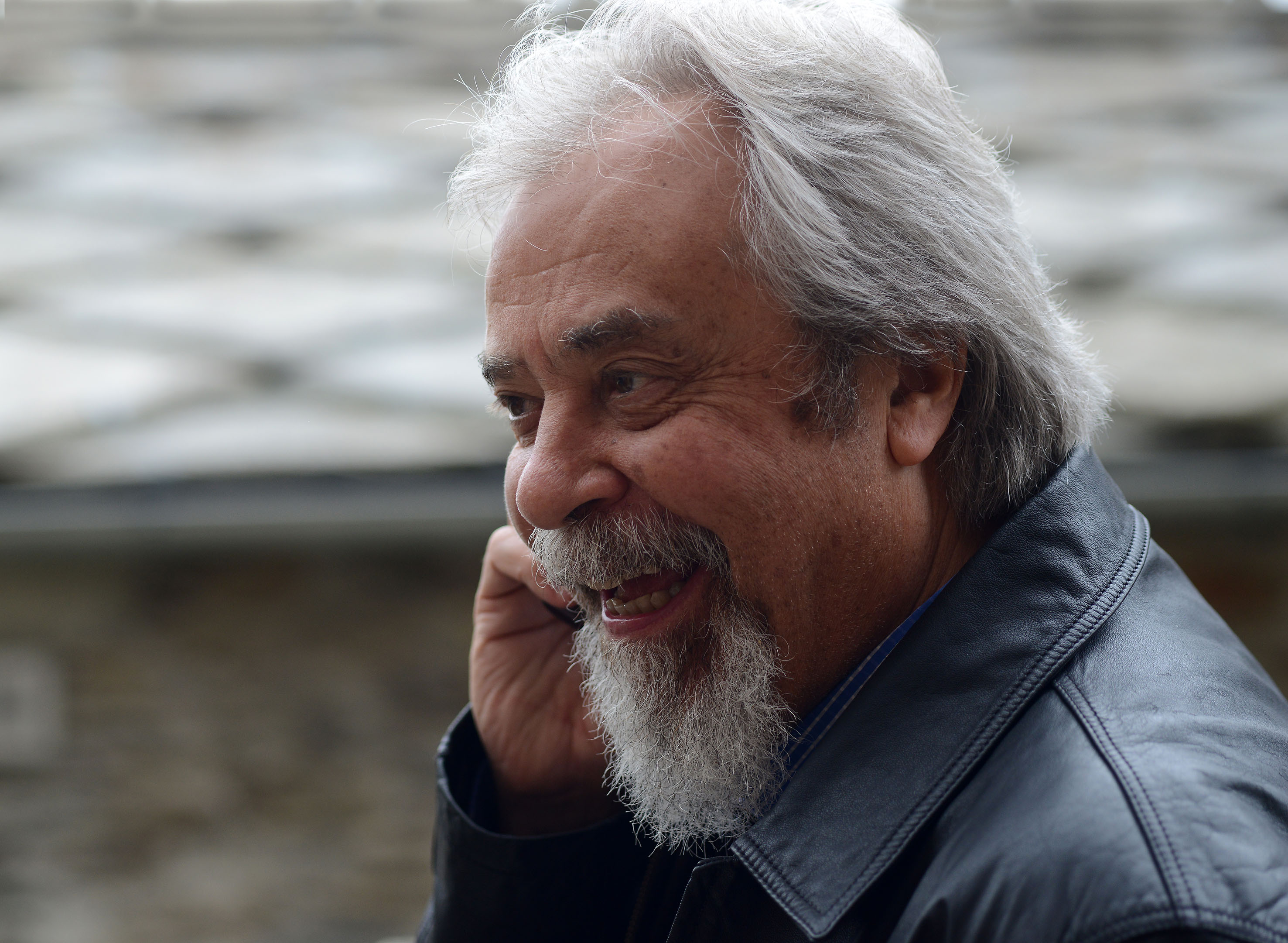

Singing Alilo in Northern Italy

Oral tradition and written sources, from the Counter-Reformation to today

The custom of singing carols known in Italian as Stella (which means “star”) or Tre Re (“the three Magi”) is well documented in Italy and in the alpine regions of Ticino in Slovenia. Moreover, the same tradition is present in vast zones of Catholic central Europe, above all in German-speaking areas but also in Bohemia, Hungary, and Slavic countries.

|

1982, Fassa valley-Penìa, Stella singers_Photo Morelli |

1982, Fassa valley-Soraga, Stella singers_Photo Morelli |

As with the Georgian practice of singing Alilo, a group of singers, often dressed as the three Magi, visit houses throughout the town in the period between Christmas and Epiphany, singing songs typically associated with the begging of alms and receiving in exchange gifts of various types. One singer traditionally bears an illuminated pinwheel-type star, or stella. Proceeds from this event might be donated to the church or divided between the “star singers” themselves.

The Stella carol and variations are performed in a traditional context, without written parts. Should they therefore be considered popular songs? That is, do they form part of a repertoire only passed on by oral tradition, or is it possible to trace the original composers and arrangers? In the event that individual authors can be traced, can the composition dates also be recovered? Up until the end of the 1980s, these questions remained unanswered.

In 1981, I began field research in the Mòcheni valley, an isolated mountain community of Germanic ethno-linguistic origins in Trentino, where the tradition of the Stella continues to be particularly strong. I was able to document fourteen different variations of the Stella carol. Twelve were set to Italian text and two were in Latin. Usually, variations of traditional songs in other regions of Northern Italy may present one, two, or a maximum of three different variations.

|

1984, Mòcheni valley-Fierozzo, Stella singers_Photo Morelli |

Photo-4-2001, Mòcheni valley-Palù, Stella singers_Photo Morelli |

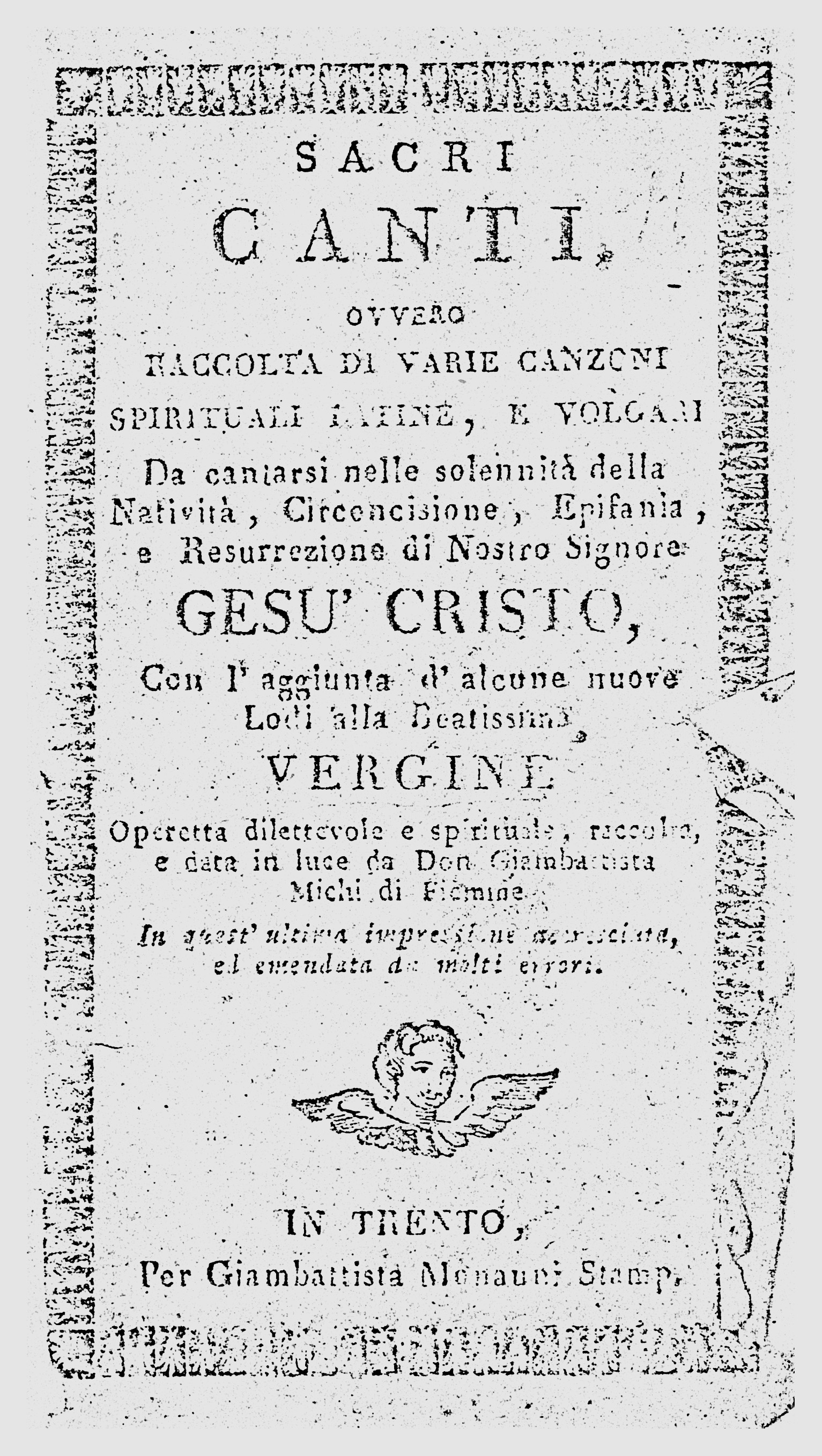

In 1984, I was finally able to locate a copy of a book that I had long been looking for: a small, 72-page volume titled Sacri Canti (Sacred carols), collected by a certain priest known as Don Giambattista Michi di Fiemme. We shall refer to this volume simply as the Michi collection.

|

Don Giovanni Battista Michi was born in Tesero on May 9, 1651, and died at the young age of thirty-nine in 1690. By dating the collection to Michi’s lifetime, it was possible to begin examining the current “oral tradition” of the various historic written sources, leading in this case to the second half of the 1600s. However, it was still necessary to shed light on the origin of the songs that Michi had published. The volume provides an introduction, dedicated to the “pious reader,” in which Michi vaguely alludes to the source of the carols: “I decided to make this present collection of Sacred Carols […] which had been scattered, and which I found in various places, partly in Latin and partly in the vulgar language.” |

.jpg)

Thus Michi most likely obtained his texts from a pre-existing popular tradition. Or he may have assembled them from previous printed sources. Ultimately he may have done both, inserting personal additions and edits along the way. Targeted research in the libraries of the conservatory of Bologna, the Valicelliana in Roma, and the British Library in London allowed me to single out several sources from the Michi collection. These sources were in part the result of a vast musical-spiritual movement promoted during the Council of Trent (1545–1563), which led to one of the most significant musical outcomes of the period: the setting of sacred texts to secular popular music, known in Italian as “laudi a travestimento spirituale.” The central figures in this process were Carlo Borromeo and the priest Serafino Razzi, who for six years during the council guided a commission of priest musicians in the compilation of songs in which various spiritual texts were adapted to widely-known popular tunes.

The purpose of this strategic and wide-ranging initiative was to resist the rise of Protestant movements from the north, where were slowly gaining a foothold in the Italian Alps. By popularizing these spiritual texts, they hoped to create a sort of spiritual barrier in “missionary territory” in order to counter what was considered the dangerous infiltration of reformist songbooks of Lutheran and Calvanist origin. These were printed in common tongues like Italian, French, Ladino-Romansh and various German languages. Five carols from the Michi collection come more or less directly from the most important collections created from this practice of overlaying spiritual texts on popular music: “Dolce felice notte,” “L’unico figlio dell’eterno padre,” “Angeli correte subito,” “Oggi è nato un bel bambino,” and “Verbum caro.”

As an example, we can examine two of these texts of Counter-Reformation origin.

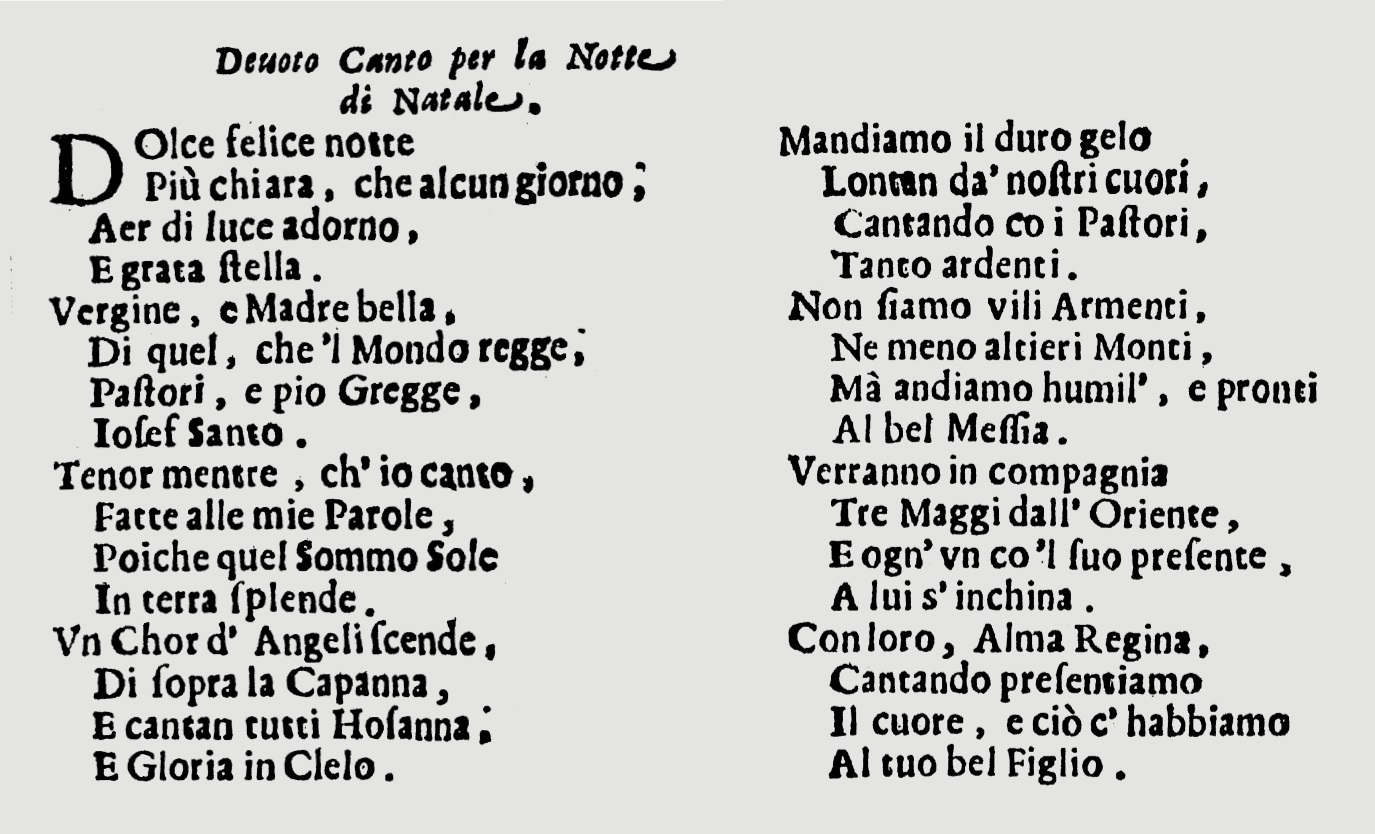

Dolce felice notte

This song was published in the Michi collection with the title “Divoto Cantico per la notte di Natale” (Devout canticle for Christmas night) with the opening words “Dolce felice notte” (Oh joyous happy night).

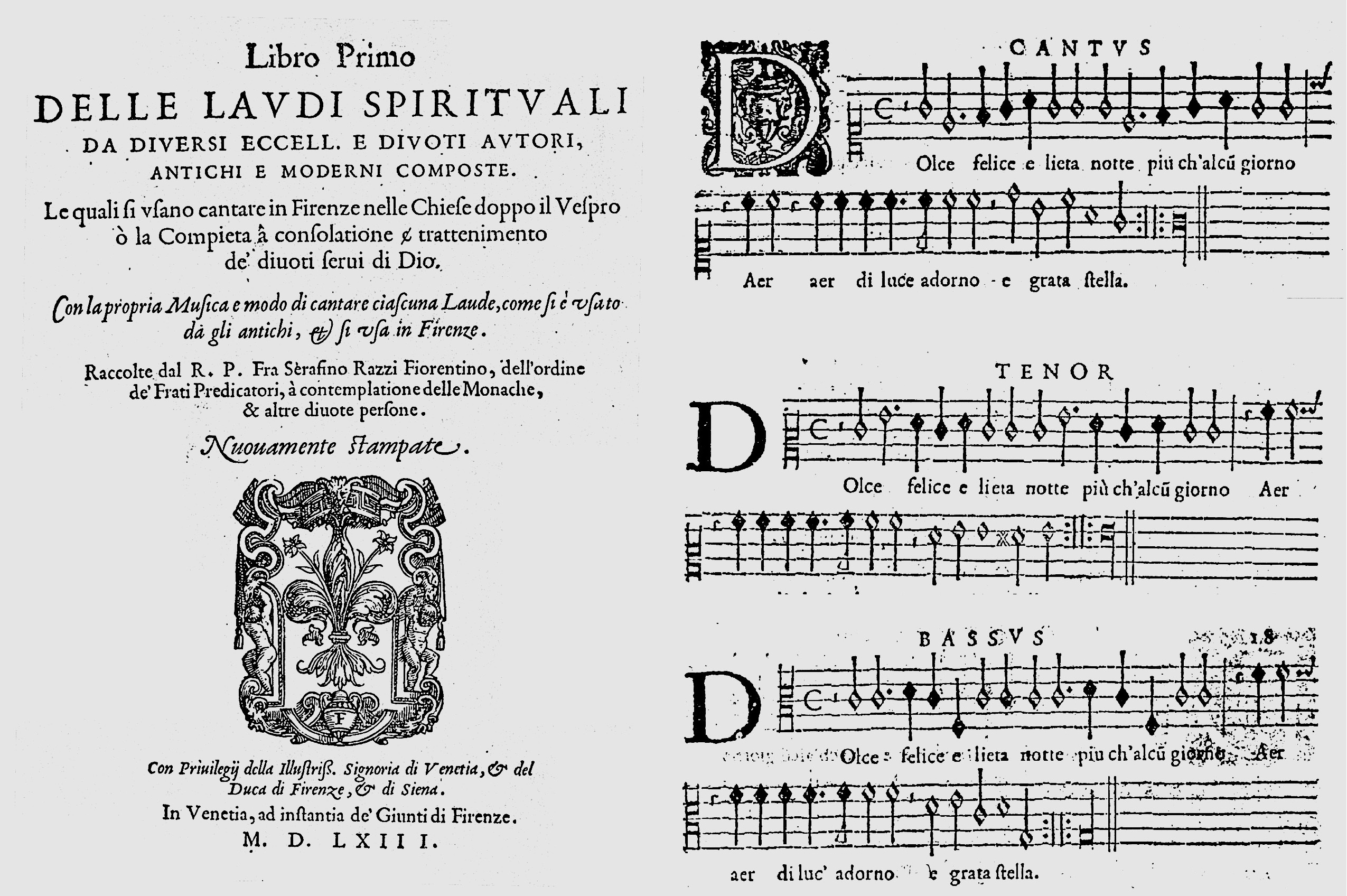

Today, this carol is widespread throughout the entire Alps. The oldest sacred source for “Dolce felice notte” is in the book Libro Primo delle Laudi Spirituali (Razzi 1563), where the song was published under the title “Laude della Natività di Giesù di Fra Serafino Razzi.”

This version by the Florentine priest was reprinted in its entirety in numerous subsequent collections, an evident sign of its apparent popularity.

L’unico figlio dell’eterno padre

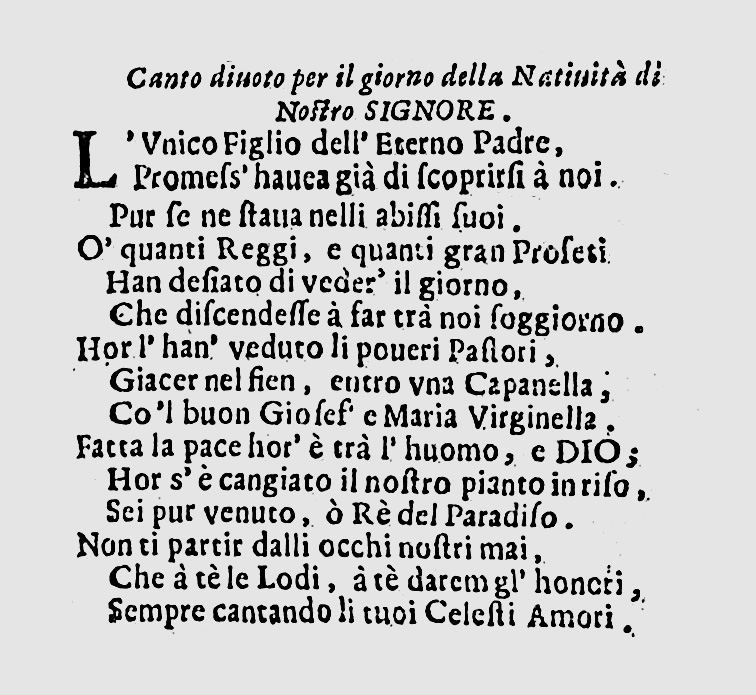

This song was published in the Michi collection with the title “Canto divoto per il giorno della Natività di Nostro Signore” (Devout song for Christmas day), with the incipit “L’unico figlio dell’eterno padre” (The only Son of the eternal Father).

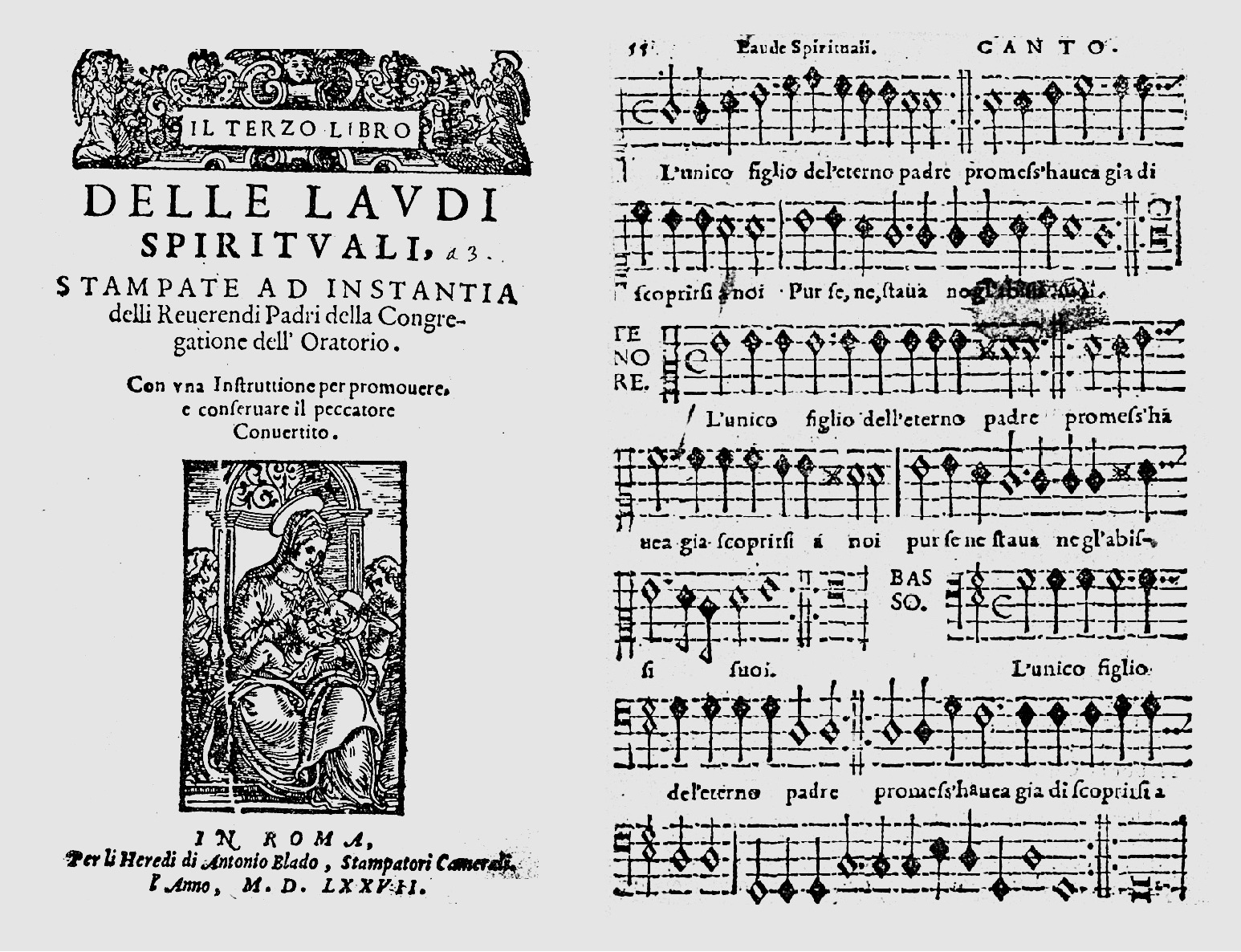

Today, this carol is also widespread throughout the entire Alps. The oldest source of the spiritual text for “L’unico figlio” is from the Terzo libro delle laudi spirituali (Terzo libro 1577) where it is produced on page 56 as follows, “Nella natività di Christo nostro Salvatore.”

This text corresponds precisely in all verses to the text in the Michi. Later, “L’unico figlio dell’eterno padre” was included in its entirety in numerous subsequent collections.

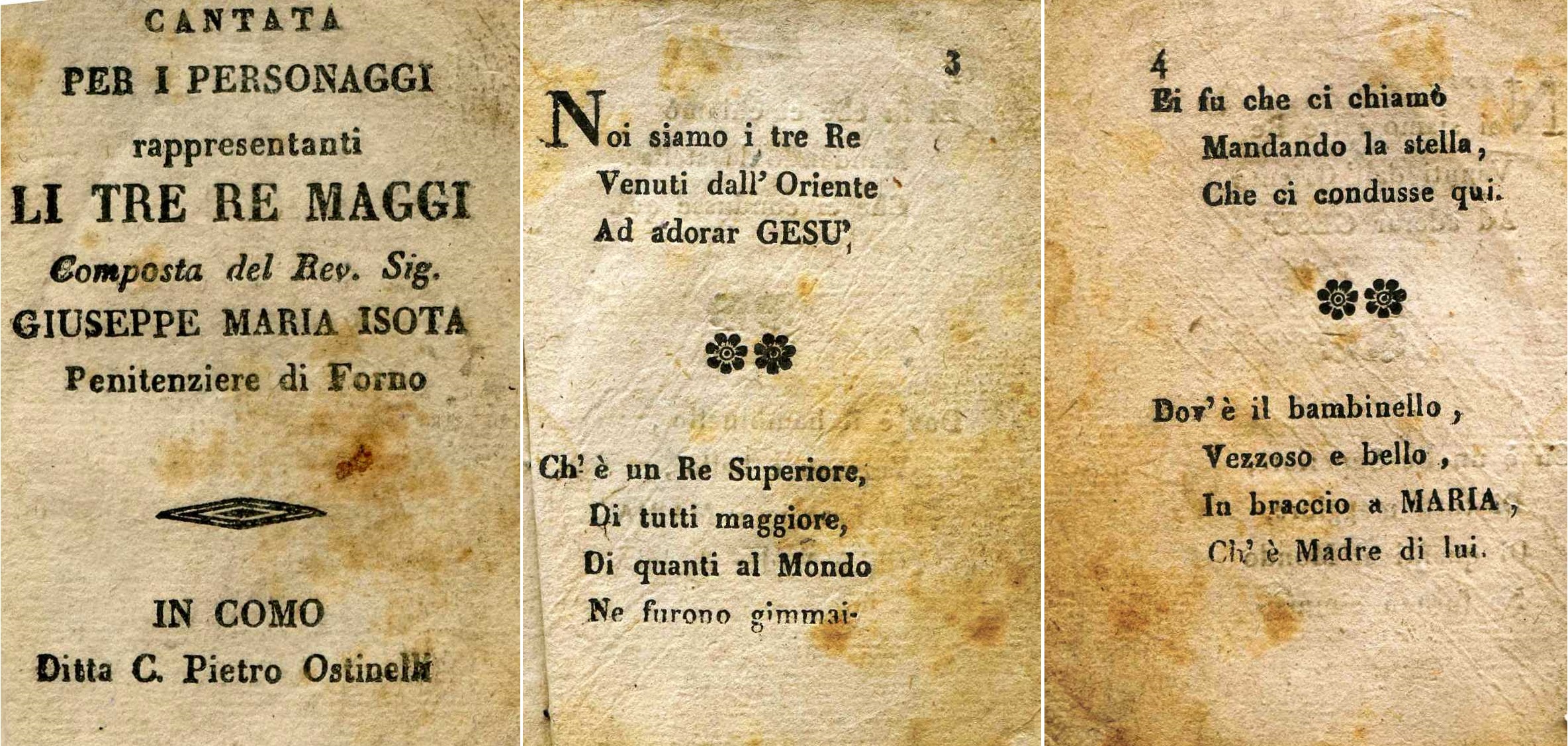

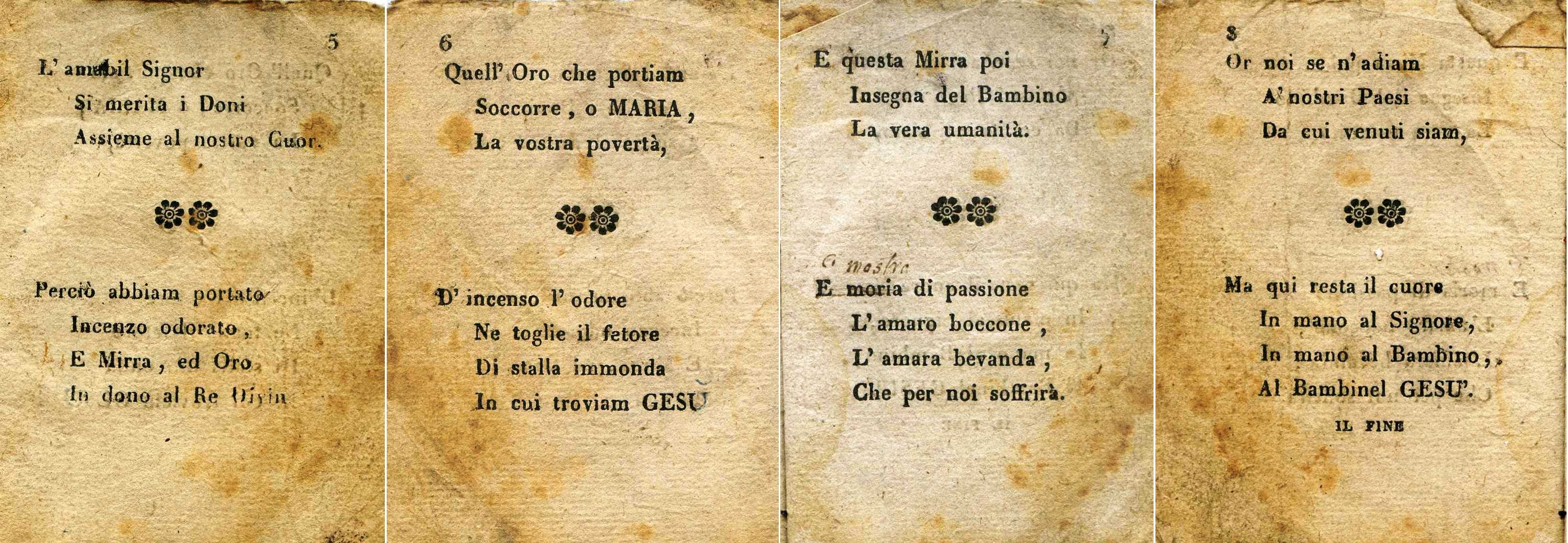

Noi siamo i tre Re

Unfortunately, this kind of research did not prove possible for all of the texts. Such is the case, for example, with “Noi siamo i tre Re venuti dall’oriente” (We are the three kings come from the East), the most widespread of the star-singer carols and well documented by various studies in its continuing tradition throughout the Alps. There is no trace of this song in either Counter-Reformation spiritual texts or in the Michi collection. This is the song used in Premana, a commune in Valsassina, where I produced the film Voices from the Heights: Three Days in Premana in 2011, documenting the local tradition of multi-part singing.

2011, Sassina valley-Premana- Stella singers_Photo Morelli

During the official presentation of the film in Premana on October 20, 2011, I had occasion to meet Professor Antonio Bellati, a noted local scholar who is considered the living memory of the town. We spoke together of this song, the difficulties in obtaining printed original sources, and the fact that really nothing was known about its origins or author. At this point, the aged historian, his memory stimulated by his own curiosity on the subject, recalled “having seen something” in his youth, and he promised to search for these vaguely remembered documents. A month later, Professor Bellati had managed to find a collection of devotional songs in Premana, obtained by cobbling together texts of various components taken from various printed booklets. Among them was a “song for the characters representing the three Magi,” which contained the complete text of “Noi siamo i tre Re” in the version used in Premana.

In this case, too, the title page does not give the date of publication, but it does note the publisher (Piero Ostinelli) as well as the author: the reverend Giuseppe Maria Isota, a “penitent” from Forno. With his usual thoroughness and skill, Professor Bellati also managed to reconstruct the biography of the priest, who was born in 1732 and died in 1794. For the first time, thanks to this document found right there in Premana, it was possible not only to name the author of the most widespread star-singer carol in the Alps, but also to know the date of its composition, thanks to the detail of our “penitent.” “Noi siamo i tre Re” was in fact composed between 1759 and 1774, when Father Giuseppe Maria Isota was in Forno, in Val Strona, as a penitent.

Fortune, decline and rediscovery

The success of the Stella carols is documented up to the end of the seventeenth century, when a gradual decline began. Subsequently, the custom was strictly prohibited by both civic and religious authorities. These bans initially concerned the Germanic territory north of the Alps but then moved slowly south. A prime example was the Bishopric of Trent, where the custom of the Stella became the object of a series of imposing prohibitions and bans pronounced by the Prince Bishop himself each Christmas Eve for thirty-three years, from 1737 until 1770. The motive behind these prohibitions can be deduced from the actual text of the proclamations: Sacri canti, according to the edicts, devolve into “bacchanals” of feasting and “other profane songs with various types of musical instruments.” Transgression of the ban was punishable by arrest and imprisonment. It is therefore probable that the bishop’s edicts managed to eradicate this custom—which was “otherwise worthy of praise”—at least in larger centres.

Destiny is not without irony however, as beginning in 1959 the custom enjoyed a renewal organized by the German and Austrian Church, bringing together large numbers of youth in solidarity projects. Between 1959 and 2015, funds totalling around € 950 million were raised in support of almost 70,000 children’s assistance programs in Africa, Latin America, Asia, Oceania and Eastern Europe. In 2015, the Stella songs, along with other carols, were added by Germany’s UNESCO commission to the Nationwide Inventory of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

SOURCES OF DEVOTIONAL SONGS (LAUDI SPIRITUALI)

Razzi (1563)

Serafino Razzi, Libro primo delle laudi spirituali da diversi eccell. e divoti autori, antichi e moderni composte. Le quali si usano cantare in Firenze nelle chiese doppo il Vespro ò la Compieta [...]. Con la propria musica e modo di cantare ciascuna laude, come si è usato da gli antichi, et si usa in Firenze. Raccolte dal R. P. Fra Serafino Razzi fiorentino, dell’ordine de’ Frati Predicatori [...]. Nuovamente stampate, Venezia, Giunti, 1563 (Francesco Rampazetto).

[RISM B/I, 15636]

Terzo libro (1577)

Il terzo libro delle laudi spirituali, stampate ad instantia delli Reverendi Padri della Congregatione dell’Oratorio. Con una instruttione per promuovere, e conservare il peccatore convertito, Roma, eredi di Antonio Blado, 1577.

[RISM A/I, A 1239; RISM B/I, 15773a]

Further Reading:

Morelli, Renato. 1996. Identità musicale della Val dei Mòcheni: Canti e cultura tradizionali di una comunità alpina mistilingue. Trento: Publistampa.

Morelli, Renato. 1997. “Formen des Dreikönigslieder in den deutschen und ladinischen Sprachinseln im östlichen Trentino.” In Beiträge zur musikalischen Volkskultur in Südtirol, Bd. 17, edited by by Walter Deutsch and Gerlinde Haid, 284–313. Wien: Böhlau.

Morelli, Renato. 2011. “L’unico figlio dell’eterno padre … Eine Sammlung geistlicher Lieder der Gegenreformation und ihr Fortleben in der mündlichen Überlieferung der Gegenwart.” In Volksmusik in den Alpen: Standortbestimmungen, edited by Thomas Nussbaumer, 163–83. Innsbruck: Universitätsverlag.

Morelli, Renato. 2014. Stelle, Gelindi tre re: Tradizione orale e fonti scritte nei canti di questua natalizio-epifanici dell’arco alpino dalla Controriforma alla globalizzazione. Udine: Nota.

Morelli, Renato. 2020. “Christmas Carols in Northern Italy: Oral Tradition and Written Sources from the Counter-Reformation to Today.” In Good Tidings Made Visible: Re-enactments of the Nativity from the Middle Ages to the Present, edited by Lenke Kovács and Francesc Massip Bonet, 151–189. Kassel: Reichenberger.

Morelli, Renato. 2014. Voci alte: Tre giorni a Premana. Venezia: Edizioni Fondazione Levi. With DVD.

Cover image: 1982, Fassa valley-Penìa, Stella singers_Photo Morelli