The Magic of New Year’s Day

New Year’s Day marks the renewal of faith and hope, a holiday full of impressive, colorful spectacles and various rituals. In Svaneti, the ancient beliefs and ideas related to this holiday have been well preserved in everyday life.

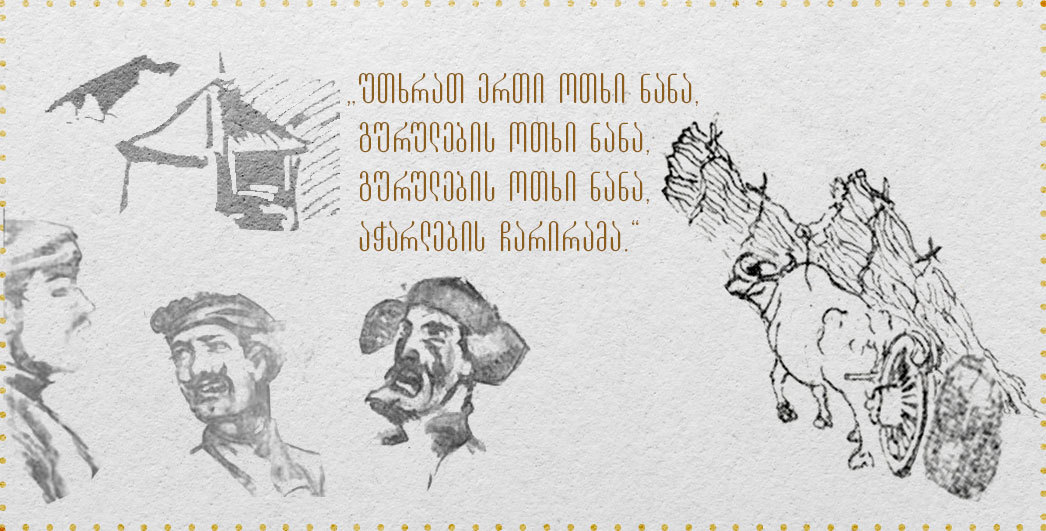

This mysterious photo — taken in in 1929 in by the ethnographer Dina Kozhevnikova in the village of Matshvarish, part of the Latali community of Upper Svaneti, in the family of Guar Girgvliani—depicts a tradition known as mekvleoba[1] on the morning of New Year’s Day. It captures an important fragment of the extensive magical rites that were performed on this day: the moment when the mekvle (the first visitor on New Year’s Day) goes around the hearth leading a bull and holding a basket of sacred objects.

People happily looked forward to the coming of the new year—Zomkha in Svan, literally zai (year) and makhe (new)—and made extensive preparations. According to their beliefs, the prosperity that awaited them next year largely depended on these very rites and rituals.

Mekvleoba was one of the main moments of the holiday. In Svaneti, there was a tradition of having two mekvles visit the family on the first day of the new year: the household mekvle (khora mech’shkhi) and the outside mekvle (kame mech’shkhi). This tradition was meant to ensure that the new year began “on the right foot” and has been preserved to the present day. Both mekvles, as well as the bull, are chosen by vote on the previous day.

At dawn, the house mekvle would gather four special objects (a pig’s head, ritual breads, a budding branch of a hazelnut tree, silver coins...), as well as a basket for seeds and an empty water vessel, and together with the family’s best bull, selected in advance, he would first go to the spring, wash his hands and face, and give the bull a drink of water. He would then fill the vessel with spring water, say a prayer, and return home with the bull. Before entering the house, he would stop at the threshing floor, build a “tower” of snow in the middle, put the branch with the buds of the hazelnut tree on it, and go around it with the bull while reciting prayers. The house mekvle would enter the machub (the first-floor living space in a Svan house), stepping first with his right foot. He would then go around the hearth three times, saying prayers and supplications and leading the bull inside with him. He would then tie the bull to a pole and throw some hay on the ground for it. The family members would drink the water brought by the mekvle, which was symbolically called “milk,” and wash their hands. The head of the family would circle each family member on the right with a wooden bowl filled with with ritual breads, libations (zedashe, usually a local hard alcohol) and a pig’s head, reciting a personal blessing and performing lishiashal,[2] a ritual handshake. In the meantime, the pre-selected “outside” mekvle would arrive. Upon entering the house, this outside mekvle would mix sweets and grains and circle the hearth three times while reciting prayers and giving blessings. The people at home would greet him with sweets and well-wishes for the new year. The snow brought into the house when the mekvle entered was seen as a symbol of purity and cleanliness.

It should be noted that, alongside Christian beliefs, pre-Christian practices dedicated to reproduction, fertility, and the cult of ancestors, occupy an important place in the New Year’s celebrations. During these rituals, the bull performed an important function as a symbol of the family’s strength and prosperity. The tradition of performing mekvleoba with a bull as a sacred animal, which used to be common in almost all parts of Georgia in ancient times, has been best preserved in Svaneti. Great importance was also attached to the ritual of lighting the hearth fire by family members and the mekvle, along with related magical actions in the New Year cycle celebrations.

[1]Translatoer’s note: mekvleoba refers to “being first to visit on New Year’s Day.” According to tradition, the first guest of the new year is a bringer of good luck, similar to other “first foot” traditions practiced around the world.

[2]Lishiashi literally translates as “from hand to hand” (“shi” is the Svan word for “hand”).