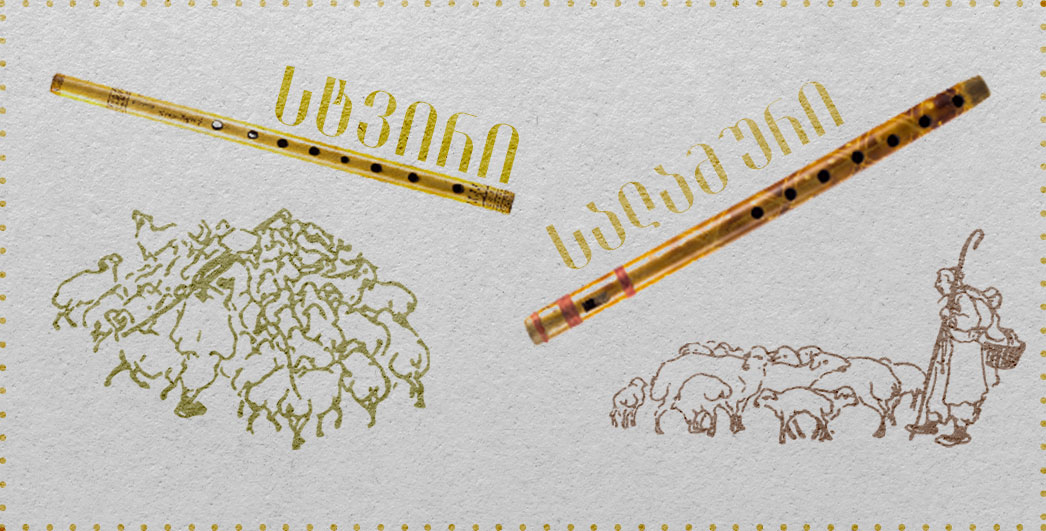

St’viri or Salamuri?

All over the world, wherever there is a culture of domesticated animals, there are shepherds. And wherever there are shepherds, there is an instrument like the Georgian salamuri, a wind instrument similar to a recorder. The salamuri is a working tool for shepherds, a means to establish sonic contact with the animals.[1]

|

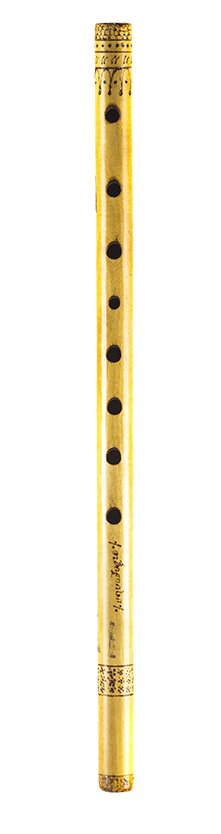

Salamuri - © STATE MUSEUM OF GEORGIAN FOLK SONGS AND INSTRUMENTS |

It is interesting to consider the name used in Georgia to this instrument. Perhaps surprisingly, many people—and more importantly, the shepherds themselves—refer to it as st’viri, or “pipe.” We see this in related terms, as well, for instance in the word referring to a player of this instrument: no one says me-salamure, rather me-st’vire. Likewise the word for “bagpipe,” which has salamuri-like pipes attached to the animal-skin bag: not guda-salamuri, but guda-st’viri. Animal husbandry—and associated practices like playing pipes—has been widespread in Georgia since ancient times. This is evidenced by the so-called “shepherd boy's salamuri,” a bone flute found in the archaeological excavations in Mtskheta (click here).[2] The historian Ivane Javakhishvili called this discovery the “shepherd boy's grave” with no mention of the salamuri. The expression “"shepherd boy’s salamuri” entered scholarly literature later. The word salamuri, most would agree, is pleasant to the ear, and it has become established in literature and poetry. The question is: which is correct, st’viri or salamuri? And it’s a fair question! Are these names, perhaps, simply dialectical variations? To get to the bottom of this, we need to turn to the old sources. |

The great Georgian lexicographer Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani (1658–1725) defines the terms st’viri and salamuri in several places in his dictionary. According to his dictionary, the general term for wind instruments is nest’vi “Instruments that are blown with the mouth are called nest’vi, as are those that have a narrow opening”.[3] Dimitri Araqishvili refers to the instrument as salamuri-st’viri and remarks: “st’viri is the accepted term in Kakheti, while in Kartli it is called salamuri,” which is a small but important note and deserves to be looked into further.[4] Manana Shilakadze, the author of many works on Georgian instruments, also notes that most people say st’viri rather than salamuri.[5]

|

Chiboni - © STATE MUSEUM OF GEORGIAN FOLK SONGS AND INSTRUMENTS |

Gudastviri - © STATE MUSEUM OF GEORGIAN FOLK SONGS AND INSTRUMENTS |

In his book on the history of Acharan instrumental folk music, Aleksandre (Ali) Mskhaladze separately discusses the predecessor instruments of the ch’iboni (bagpipes), namely, children’s instruments such as the ch’qipina or shtviri, and ch’iboni, the second of which caught my attention.[6] This term was widespread in Upper Ach’ara and the Mach’akhela valley. Davit Alavidze mentions that according to the famous mest’vire Levan Zubiashvili, the folk name for the instrument of the higher register than salamuri was st’veni or st’vini, which can also mean “whistle.”[7] It is worth noting here that some storytellers in Eastern Georgia refer to the as sht’viri.[8]

|

Ueno Salamuri - © STATE MUSEUM OF GEORGIAN FOLK SONGS AND INSTRUMENTS |

The famous historian Ivane Javakhishvili, one of the first researchers on Georgian music, concluded, based on Sulkhan-Saba’s dictionary, that nest’vi is a word with a wider meaning than [Orbeliani’s definition referring to wind instruments with narrow openings] and that it referred to all kinds of pipes. But if one observes, one will see that originally the word nest’vi was intended only to express the idea of whistling, and denote an object, or part thereof, that whistled.[9] Javakhishvili's remark that the word salamuri “does not appear in the Georgian canonical texts” is significant, it is impossible for the salamuri to have evaded Ivane Javakhishvili in those textsIt is unlikely that Ivane Javakhishvili overlooked the term 'salamuri' in those texts..[10] It is true that this word is not unknown to Sulkhan-Saba, but it seems that the salamuri does not appear anywhere in earlier sources! Sulkhan-Saba, for his part, refers to the salamuri as zurnaika and considers it a synonym of nest’vi.[11] Davit Guramishvili also calls it nest’vi in one instance, and st’viri in another (“I heard the sound of the st’viri”).[12] Accordingly, based on the comparison of the discussed sources, we can conclude that though Sulkhan-Saba was familiar with the term salamuri, he preferred nest’vi and st’viri when describing the instrument. It seems that salamuri must not have been a very common term at that time, and most importantly, Ivane Javakhishvili's research shows that it did not appear in older sources. |

Naturally, a fair question arises: what is the etymology of the word salamuri and how did it enter the Georgian musical vocabulary? By phonetic association, one might think it is related to salam-kalami, a term meaning “greetings” or “small talk,” derived from the Arabic as-salāmu ʽalaykum (peace be upon you)—but perhaps it came from a completely different direction? A Modern Greek dictionary helped clarify this: to our surprise, we found that salamoura (σαλαμούρα) means “salt water” in Greek.[13] But what does saltwater and salamuri have to do with each other? From our own expedition materials, in particular from shepherds’ stories, we learned that sometimes reed salamuris were made from very soft branches and, to make them more durable, were soaked in brine.[14] This seems to answer our question.

All of the above, I think, proves that st’viri is a Georgian word, and salamuri is not. Salamuri is nowhere to be seen in ancient sources. It is a fact that salamoura means saltwater in Greek. It is also a fact that the shepherds used to soak elder branches or reed stalks in saltwater. However, the question of how the Greek word salamuri came into the vocabulary of Georgian shepherds remains unanswered. This is the subject of future studies, in which, I think, historians should be involved.

[1]I have observed this use of the instrument in my own fieldwork. See also Shalva Aslanishvili, Nark’veebi kartuli khalkhuri simgherebis shesakheb (Essays on Georgian folk songs), vol. 1 (Tbilisi: Metsniereba, 1958), 46; Manana Shilakadze, Kartuli khalkhuri sak’ravebi da sak’ravieri musik’a [Georgian folk instruments and instrumental music) (Tbilisi: Metsniereba, 1970), 33.

[2]See Grigol Chkhikvadze, “The Prehistoric Georgian Bone Salamuri Flute,” in Essays on Georgian Ethnomusicology, trans. Ariane Chanturia (Tbilisi: International Research Center for Traditional Polyphony, 2005), 164–69.

[3]Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani, Leksikoni kartuli (Georgian dictionary), vol. 1(Tbilisi: Merani, 1991), 590–91.

[4]Dimitri Araqishvili, Khalkhuri samusik’o sak’ravebis aghts’era da gazomva (Descriptions and measurements of folk musical instruments) (Tbilisi: Teknik’a da shroma, 1940), 16.

[5]Shilakadze, Kartuli khalkhuri sak’ravebi, 33.

[6]Aleksandre Mskhaladze, Ach’aruli khalkhuri sak’ravieri musik’is ist’oriidan: ch’iboni da misi t’raditsia ach’arashi (From the history of instrumental folk music of Ach’ara:The ch’iboni and its tradition in Ach’ara) (Tbilisi: Metsniereba, 1969), 15.

[7]Davit Alavidze, Kartuli da sakartveloshi gavrtselebuli khalkhuri musik’aluri sak’ravebi Georgian folk musical instruments and those widespread in Georgia) (Tbilisi: Khelovneba, 1979), 53.

[8]Alavidze, Kartuli da sakartveloshi, 53.

[9]Ivane Javakhishvili Kartuli musik’is ist’oriis dziritadi sak’itkhebi (Main questions in the history of Georgian music) (Tbilisi: Pederatsia, 1938), 99.

[10]Javakhishvili, Kartuli musik’is, 197.

[11]Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani, Leksikoni kartuli (Georgian dictionary), vol. 2 (Tbilisi: Merani, 1993), 35.

[12]Orbeliani, Kartuli leksik’oni, vol. 2, 111.

[13]Georgios Babiniotis (Mpampiniōtēs), Lexiko tēs neas Hellenikēs glōssas (Dictionary of Modern Greek), 2nd ed. (Athens: Kentro lexikologias, 2002).

[14]Expedition materials, including interviews with Leri Nakvetauri, a shepherd from Ts’ovata in Tusheti (1976) and Ioseb Gonjilashvili, a shepherd from the, village of Magraneti in Tianeti (1976).