Shape Note Singing and Folk Music Practice

Shape note singing, also commonly known as Sacred Harp singing, is a North American musical practice that has existed for slightly more than two centuries. The music is sung in four-part harmony by singers who sit in rows, encircling a single leader who stands in the centre of the room. It is a democratic and egalitarian tradition in which newcomers are welcomed, and any participant, from the youngest to the oldest, gets to choose a song and lead the entire group from the centre in turn.

While the repertoire has religious roots, it is not sung as part of a religious worship service, but rather in gatherings that bring together Christian believers with non-believers who are drawn primarily by the music and its associated aesthetics.[1] All the attendees at a shape note singing event sing from the same tunebook. The most commonly used of these books is called The Sacred Harp, lending its name to the entire tradition, but many others exist, including some still used today like The Shenandoah Harmony and The Christian Harmony.

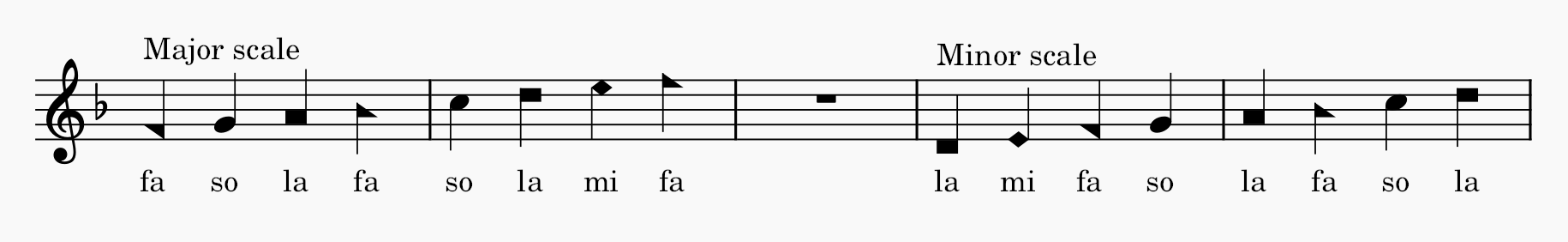

The music is referred to as "shape note" because the musical notation employs noteheads of different shapes (see figure 1). [2] This is intended to facilitate sight-reading, musical literacy, and part singing. At the time shape note notation was invented in New England in the late 1700s, much congregational church singing was monophonic, drawn out, and hard to follow, leading to dissatisfaction among the musically inclined. Shape note music was popularized by travelling teachers, who would bring cartloads of tunebooks to different communities, spend a few weeks selling their books and teaching the new musical system, and then travel on to the next community.

By the 1840s, many shape note tunebooks had been published, and the tradition of regularly gathering to sing outside of the worship service especially took hold in the American southern states, where it has remained a living tradition until today. Shape note singing eventually disappeared in the northern states, but it experienced a revival in the 1960s and 1970s, in the context of the more general folk music revivals of that time in North America. For this reason, the American South is regarded as the source of authentic shape note practice today.

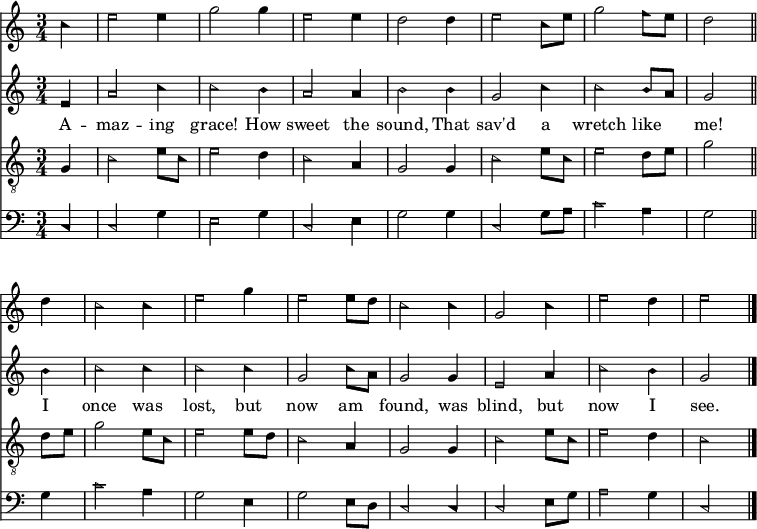

In the most common shape note system used today, the first major scale degree (called "fa") always employs a triangular notehead, the second scale degree ("so") a round notehead, the third scale degree ("la") a rectangular notehead, and so on (see figure 1). Although the Western musical scale contains seven different notes before repeating at the octave, and some seven-shape tunebooks exist, The Sacred Harp and the majority of tunebooks used today employ a system of four shapes. In this system, the first major scale degree shares a shape with the fourth degree, as does the second with the fifth, and the third with the sixth, while the seventh, "mi," has its own diamond shape. This creates the major scale pattern of fa-so-la-fa-so-la-mi(-fa), or la-mi-fa-so-la-fa-so(-la) for the minor scale.[3] Most shape note tunes in The Sacred Harp and other tunebooks are now in four-part harmony, although the earliest compositions were largely in three-part harmony, with the alto line added decades later (see figure 2).[4]

The major and minot scales in the four shapes system

A four-part hymn in shape note style. From top to bottom, the voice parts are named treble, alto, tenor (the melody line), and bass.

Local shape note singing events are often held weekly or biweekly in many towns and cities across the United States, and now in many other countries as well. The group of local people meeting regularly to sing together can be considered participants in a musical subculture,[5] a connected network that spans a large geographical area but is realized in many local “scenes” or “clusters of social and cultural activity.”[6]

Bigger events called "all day singings" or "conventions" are held over weekends and usually involve one or two full days of singing (including a morning singing session followed by a meal and an afternoon of further singing, as well as unofficial evening parties and gatherings); these events may include one hundred or even more singers.

At a typical singing event, attendees take turns choosing songs; the person choosing the song also leads it from the centre of the room. Nobody is required to lead a song, but typically none will lead a second song until all those who wish to lead have taken their first turn. At bigger events, those who want to lead will sign up ahead of time to ensure nobody is missed.

I have been singing Sacred Harp music for about as long as I have taken a serious interest in Georgian vocal polyphony—close to fifteen years. In this time, I have discovered a significant overlap between non-Georgians who become passionate about Georgian music, and those who sing shape note music. (I have also met several Georgians who have sung shape note music, but this is much rarer.) This is true particularly of North American singers of Georgian music, but also of friends and acquaintances from Europe and Australia. A few things unite both styles of music: a “natural voice” approach to singing that employs chest and nasal resonance rather than classical technique, a high decibel level, an avoidance of common practice European harmony, a participatory frame for performance, an employment of vocables, an association with hospitality and cuisine, and a general perception that these are rural, authentic, and folk traditions with functional roots.

Of course, the styles of music are very different, but as group singing traditions outside the European classical canon, they attract newcomers for similar reasons (for more on this subject, see Caroline Bithell’s book, A Different Voice, a Different Song).[7] Many people who come to either Georgian singing or shape note singing as outsiders to the tradition narrate their initial encounter with these new styles as a kind of musical conversion experience, a watershed moment that shocks them with unfamiliar sounds and changes the course of their life.

Indeed, many shape note practitioners regularly drive hundreds of kilometres multiple times a year to attend weekend singing conventions in cities and regions both far and wide, just as many non-Georgian singers of Georgian polyphony end up travelling to Georgia to experience the music firsthand. Particular yearly singing events in the American southern states of Alabama, Georgia, and Tennessee attract shape note singers from distant states—Illinois, New York, Vermont, California, and many others. Southern singers also travel to northern singings, sometimes as specially invited guests, just as North Americans and Europeans often host Georgian singing teachers or vocal ensembles on concert tours. Showing the importance of welcoming newcomers and inclusivity, visiting singers are often hosted for free in the homes of the local singers hosting the singing event.

Since sacred harp events are built around a common tunebook, and the tradition is premised on the idea that all participants know (or are in the process of learning) how to decipher the musical notation in that tunebook, participants are theoretically able to attend any singing anywhere and sing any song in the tunebook, even if they have never met any of the other singers or sung that particular song before.

Of the 590 songs in The Sacred Harp, some are nearly universally known by almost all sacred harp singers. This is particularly true of songs like “Idumea,” which was featured in the 2003 film Cold Mountain and provided millions of viewers with their first experience of shape note music.[8] Given that The Sacred Harp just received a new edition in 2025, which replaced 77 songs from the 1991 edition with 113 new ones, it will take some time before the new songs become known across a broad swathe of the population. And each local group of shape note singers will favour certain songs and largely avoid others; scenes with fewer, less adventurous practitioners and less regular gatherings may limit themselves primarily to only 10-20% of the songs in the tunebook.

Shape note singing presents some challenges to notions of folk authenticity. Many ethnomusicologists recognise that the term “folk” is problematic in many ways, but it is still popularly understood to encompass the following general characteristics, as outlined in Philip Tagg in an “axiomatic triangle” that distinguishes between folk, popular, and art musics: 1) it is produced and transmitted primarily by amateurs, 2) it is locally distributed rather than subject to mass distribution, 3) it is primarily stored and distributed through oral transmission rather than musical notation or recorded sound, 4) it arises primarily in nomadic or agrarian societies, 5) written theory and aesthetics about the music is limited or uncommon, 6) the composer of the music is generally anonymous.[9]

Shape note singing undeniably meets some of these characteristics. It is a thoroughly non-professional practice; nobody is paid to attend a Sacred Harp convention, and almost nobody makes money from shape note singing, with the occasional exception of visiting teachers who lead workshops or teach classes in shape note practice. The Sacred Harp Publishing Company[10] itself is a non-profit organization that strives to keep book costs as low as possible to lower barriers to participation. Shape note singers rarely perform their songs for money, except when hired to sing in movie soundtracks or similar contexts. The shape note tradition also took hold especially in agrarian contexts, and it has remained a living tradition in places like rural Alabama and Tennessee.

Published tunebooks are essential to the practice of shape note singing—indeed, the very term “shape note” refers to musical notation. Thus, the tradition has never been oral. However, there are certain customary practices that break from the strict literal reading of the music on the page and nod toward oral tradition. For example, songs are rarely sung in the key written on the page. Instead, one of the confident participants is usually assigned the task of “keying” the song, which they do by singing a triad at a pitch level that they think will best accommodate the ranges of the singers in attendance. Further, minor key tunes are sometimes performed in the Dorian mode (with a raised sixth scale degree), with some authorities arguing that this should actually be the default, although raised sixths are not indicated in the tunebook. Knowing which songs typically feature a raised sixth requires contextual information and experience, but more often this information is not stated verbally, but simply learned in the process of performance—a classic example of oral transmission. Finally, many practitioners actually memorize the songs, including the shapes of each note, and perform without looking often at the books. This allows for additional flourishes, vocal ornaments, and variations that are not actually indicated in the notation.

The musical and textual content of shape note songs is rarely anonymous; the names of the tune’s composer and the author of its poetry are printed along with the musical notation in the tunebook. While some tunes date back 200 years or more, others were written much more recently, including some within the last decade. The 2025 edition of The Sacred Harp contains 113 new tunes by 78 composers, and 49 of those composers are still living, with one composition dating as recently as 2024.[11] In most cases, new compositions employ texts that fit the style of the religious poetry common to the tradition; in fact, they frequently use poetic texts that were written hundreds of years ago by hymn text writers like England’s Isaac Watts (1674-1748). While the tunes are newly composed, they are also written in a style that is highly informed by pre-existing shape note songs. If new compositions differed radically in style, they would likely not gain broad acceptance.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about shape note singing from the standpoint of folk tradition is the way it challenges the insider/outsider dichotomy. From one point of view, the formation of shape note singing scenes in northern and Midwestern states like New York, Illinois, and Pennsylvania can be analyzed as a process of cultural revival. However, this is not “secondary folklore” in Edisher Garakanidze’s sense. Northern singers may have “[translated] musical practices, functions, and meanings from highly localized, usually rural contexts,”[12] but they did not seek to reconfigure a participatory tradition and turn it into a staged performance. Because shape note singing was never an exclusive practice associated with a single ethnic or religious group, and was instead a network of local groups who took turns hosting and visiting, adding more nodes in the network at a further geographical remove was not seen as diluting the purity of the tradition. The newer northern shape note singers replicated the practices surrounding the tradition in the south, such as including a non-denominational prayer, a brief remembrance of singers who had recently died, and a potluck meal in the middle of an all-day singing event. While members of southern families who have sung from The Sacred Harp since birth for generations are still prized today as keepers of authentic tradition, even newcomers can come to take on leadership roles in their own local scenes once they have grown in expertise and visited enough singings in different places.

Shape note music is a once-localized tradition that now inspires passionate participation from singers across the world. It invites all to sit and join their voices together, and even become leaders and insiders to the tradition. While its appeal may be limited, it offers a unique and powerful emotional and physical experience that invites the devotion of its followers. Whatever we understand “folk tradition” to mean, this is undoubtedly a vibrant and vital practice far outside the realm of professionalized music, and its power to bring groups of people together deserves to be celebrated.

[1] Miller, Kiri. 2008. Traveling Home: Sacred Harp Singing and American Pluralism. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shape_note#/media/File:TheShapesOfShapeNoteSinging_4ShapeSystem.gif

[3] One advantage of employing four shapes rather than seven is that it makes clear the whole-tone relationship from fa to so, and from so to la, and the major third relationship from fa to the la above it, a pattern that appears within the major scale twice: from degrees 1 to 3, and again from 4 to 6.

[4] “New Britain” from The Sacred Harp, 1991 edition (page 45). https://upload.wikimedia.org/score/o/w/owhcf1tly76z65t4iq4t6eccl79slv4/owhcf1tl.png

[5] Slobin, Mark. 1992. “Micromusics of the West: A Comparative Approach.” Ethnomusicology 36(1):1-87.

[6] Straw, Will. 2004. “Cultural Scenes.” Loisir et société/Society and Leisure 27(2):412.

[7] Bithell, Caroline. 2014. A Different Voice, a Different Song: Reclaiming Community through the Natural Voice and World Song. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[8] Other commonly known tunes include “Hallelujah,” “Northfield,” “Africa,” “Redemption,” and “Stratfield.” Statistics available at https://fasola.org/minutes/stats/ reveal that “Idumea” has been among the ten most-performed tunes in The Sacred Harp since 2004, while before Cold Mountain was released, it had never reached the top forty.

[9] Tagg, Philip. 1982. Analysing Popular Music: Theory, Method and Practice. Popular Music 2: 37-67.

[11] https://sacredharp.com/2025/08/01/songs-added-sacred-harp/

[12] Bithell, Caroline. 2016. “Georgian Polyphony and its Journeys from National Revival to Global Heritage,” in The Oxford Handbook of Musical Revival. Ed. Caroline Bithell & Juniper Hill. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 573.