Georgia, the Cradle of Wine

Wine and Winemaking in Ancient Georgia

In 2017, an article entitled “Early Neolithic Wine of Georgia in the South Caucasus” was published. This article aroused great international interest, as it confirmed, through comprehensive research, that wine was being pressed in Georgia as far back as eight thousand years ago. The fact is that this date precedes the findings in the Zagros Mountains (Iran), which was previously the earliest evidence of wine culture, by six hundred years.

However, interest in Georgian wine was great even before this discovery. This is evidenced, for example, by the fact that some years ago, Bordeaux, known as the city of wine, hosted an archeological and ethnographic exhibition of the Georgian National Museum, which reflected the centuries-old history of Georgian wine. Even earlier, in 1999, the exhibition space Vinopolis (Wine City) opened in London, which featured a Georgian corner with the title “Georgia: Homeland of Wine”.

In general, the theory that Georgia is the homeland of wine has been around for a long time. The Georgian academic community, based on rich archaeological, ethnographic, and folkloric data, suggested that Transcaucasia and the territory of Georgia were the oldest areas of viticulture and winemaking (Chilashvili 2004). This theory has also been supported by the continuous and diverse folk traditions related to wine and viticulture. In the 1980s, the famous writer Hugh Johnson named Georgia as the probable homeland of wine in his book, Vintage: The Story of Wine (Johnson 1989). A similar view was expressed by Patrick McGovern, a renowned wine historian and professor at the University of Pennsylvania, in his 2003 book Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture.

In addition to circumstantial evidence (e.g., folklore heritage, ritual practices, etc.), the existence of a wine culture in ancient Georgia is materially substantiated. During archeological excavations in the mid-twentieth century, grape seeds were found in the Eneolithic layers, which garnered a kind of sensation. It was then, for the first time, that a cautious assumption was made that viticulture already existed in Georgia in the period between the third and second millennia BCE.

The probable date became even earlier when grape seeds were found in the Neolithic strata at the archeological sites “Khrami Didi Gora” and “Dangreuli Gora” in Shulaveri (Kvemo Kartli). This time, the period of conception and development of viticulture and winemaking in our country was identified as the fifth to sixth millennia BCE. All of this, however, remained speculative due to the lack of accurate laboratory data.

Apart from grape seeds, other archeological materials indicate that wine was indeed being pressed from grapes. A kind of clay vessel, which is an ancestor of today's Georgian kvevri, though slightly different from it, belongs to this period, although the kvevri had different purposes and was not used only for winemaking, but also for storing grain. Moreover, for many centuries, kvevri were widely used for burial: the deceased were placed in special kvevri and buried that way.

During the Mtkvari-Arax cultural period, in the third to second millennia the kvevri were shaped like pitchers, with narrow bottoms, wide necks, and thick walls, and were placed in low pits, half-buried in the ground. The surface of the jars seems to have been refined, polished, and embellished with geometric figures, spirals, and images of birds.

|

A large wine vessel, Khramis Didi Gora. Neolithic period. |

The practice of placing the kvevris completely in the ground developed in the middle of the first millennium BCE. Winemaking technology gradually evolved and improved, and subsequently, at the turn of the millennium, wineries appeared. According to the rich archeological data, there is thus no doubt that during this period, Georgia’s viticulture and winemaking prospered and occupied an important place in agriculture. In addition to archeological data, written sources also indicate the antiquity of Georgian wine. One of the oldest Kartvelian tribes, the Mushkis (or Meskhetians), seem to have especially loved wine because, according to Assyrian sources, in the country of the Meskhetians, wine was abundant. Homer also describes the sparkling wine of the Phasis (Colchis) region with praise. According to this legend, the Argonauts who came to Colchis were amazed by the vineyards and the wine fountains. |

A rather interesting piece of information about the homeland of viticulture and winemaking is preserved in the works of the famous Iranian mathematician and poet, the great wine lover, Omar Khayyam. The poet testifies to one historical narrative:

Prince Badem, the son of the famous King Shamiram, saved a phoenix from death, by strangling a huge snake. The grateful bird brought the king grape seeds. The king ordered the seeds to be sown, and then wine to be made from the grapes. The drink was considered a source of pleasure. Vineyards were planted throughout the country, for the benefit of the people (1).

According to the tale, the mythical phoenix flew to Persia from the north. Terms denoting the North and South Caucasus coincide in Persian (according to ancient Hebrew legends, the wine is native to the South Caucasus). Consequently, this mythological narration of Khayyam echoes the scientific hypothesis that the South Caucasus is the homeland of wine, that is, the place where the phoenix gathered the grape seeds.

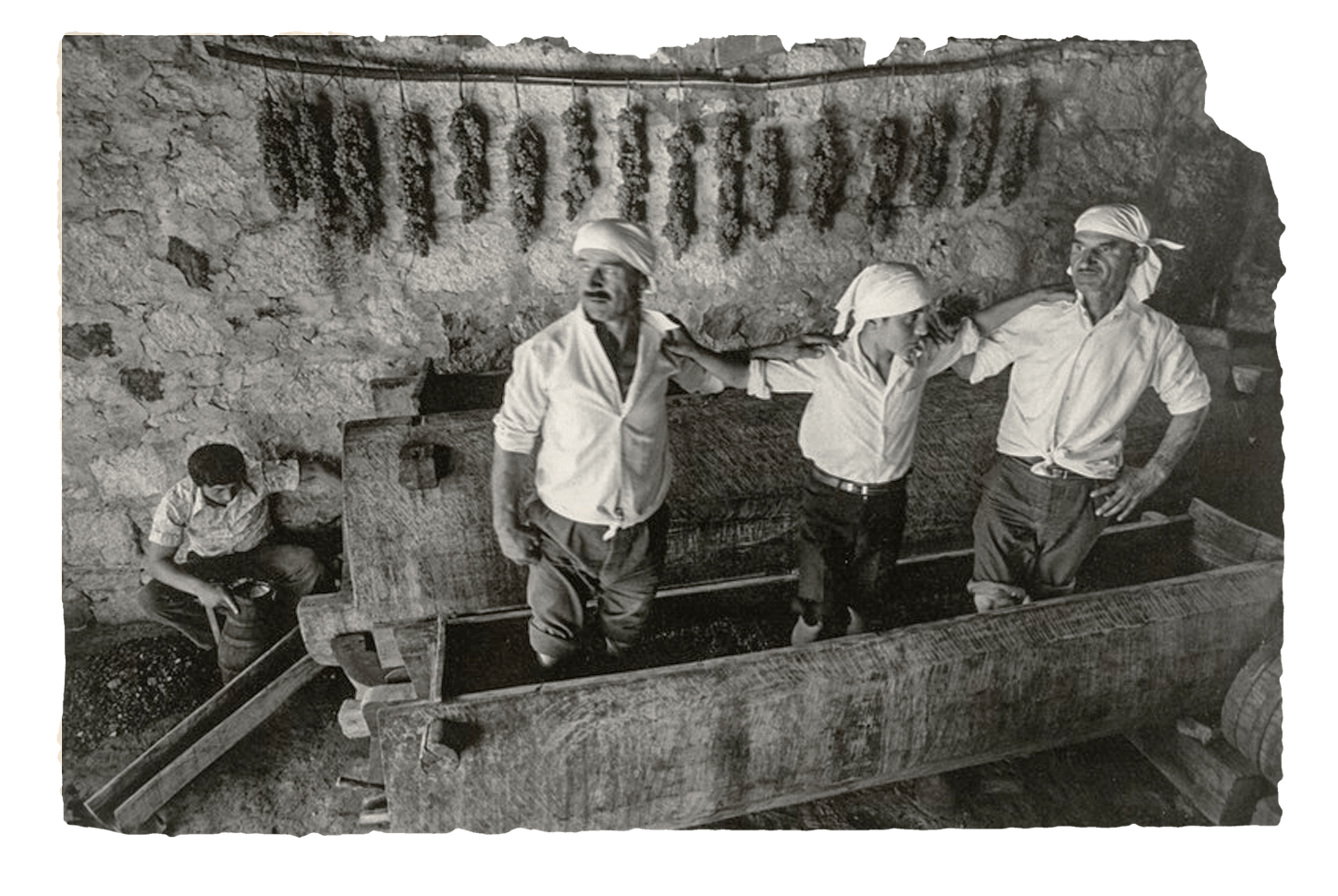

Pressing the grapes. "Iveriel" Digital Library of the National Parliamentary Library of Georgia

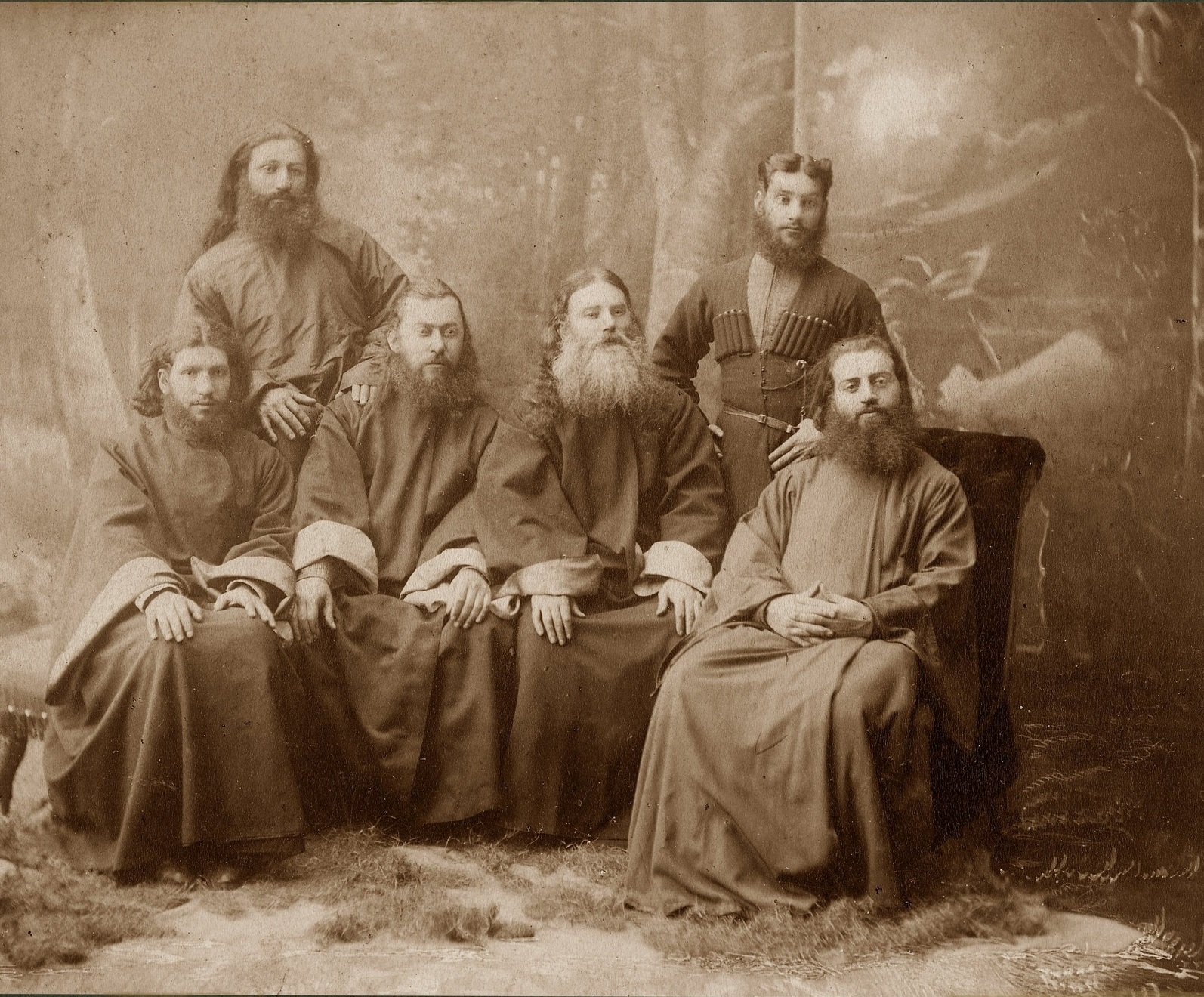

The Cult of Aguna and Wine-Drinking Culture in Georgia

Wine, wine cellars, and vineyards are all very special for Georgians and have a religious significance. According to both archeological findings and folklore, wine has had a sacral, mystical purpose since ancient times. According to ethnologists, the cult of the Greco-Roman gods Dionysus/Bacchus must have been rather widespread. This theory is often supported by toponymical evidence. For example, Bakhvi and Askana are famous viticultural villages in Guria. Scholars associate Bakhwa with Bacchus, and the etymology of Askana is probably associated with the name of Ascanius, the son of Aeneas.

The ancient Georgian deity of wine must have been Aguna. Aguna, also known as Angura, is the god of vineyard fertility and crop prosperity. Rituals dedicated to him were preserved in western Georgia (especially in Guria and Lechkhumi) until recently. Interestingly, in Persian angur is the word for “grape.” Greco-Roman and Persian parallels indicate that the Georgian world was actively involved in the world cultural centers of that time. Wine was connected and cultural exchange took place in the process of wine.

The cellar, a place for aging and storing wine, was considered a sacred place in later times. The main ritual of almost all religious holidays was performed in cellars and vineyards. Baptisms and weddings often took place in wine cellars as well. The best wines were often named after saints. Such wines were called zedashe. There were zedashes named after St. George, the Archangels, the Virgin Mary, and so on. Very often the kvevri in which these wines were made were buried in churchyards. In the parts of Georgia where grapevines did not grow, wine was brought from the valleys. More often than not, sweet (badagi), young, fresh wine was brought to the mountain villages and poured into kvevri there.

In the late Middle Ages, the Venetian ambassador Contarini wrote,

“Georgians consider the abundance of wine to be the best marker of hospitality.” Arcangelo Lamberti, while visiting Samegrelo in the mid-seventeenth century, described the attitude of Georgians towards wine as follows: “He who drinks a lot without losing his mind is considered a worthy man” (2).

The sketchbook of Castelli, an Italian missionary of the same period, contains sketches—with such titles as “a wine-drinking ceremony,” “the bride is toasted,” “the toasting pose,” “a man drinking while kneeling before a woman,”—which convey the rules and order of wine-drinking in Georgia. Castelli notes in his memoirs: “Georgians are big wine-drinkers; women are very restrained in drinking. I have attended many feasts and have never seen a woman drinking wine, while men, from first to last, drink. It turns out that men also drink wine in front of women and use shoes instead of glasses. The bishops also kneel in front of women when drinking wine, which seemed wild to us” (3).

A nineteenth century Russian traveler was surprised to note:

“Here [in Georgia] people drink a lot. They drink so much that neither the French, nor the Spaniards, nor the Italians, nor the Greeks can match them. And yet there was no case of drunkenness” (4). A century earlier, the famous French traveler Chardin also noted the self-restraint of Georgians while drinking, along with the abundance, variety, and highest quality of wine: “I can say that there is no other country where they drink so many and such excellent wines.” (5).

The Chkhubinashvilis’ wine harvest, 1905. "Iveriel" Digital Library of the National Parliamentary Library of Georgia

Vine Polyphony

The first Georgian geographer Vakhushti Bagrationi also notes the diversity of grape varieties and wines in Georgia: Kakhetian wine is “kind and good,” and he particularly distinguishes Kondoli wines and calls them “noble.” Kartlian wine is sour and watery, but delicious to drink. Wine from Ateni he considered to be the best wine in Georgia overall. Imeretian wine is also more watery, but it is delicious. As he explains, it is lighter than the wines of Guria and Samegrelo, but it is fragrant and healthful. He also mentions Zerdagi, a Megrelian wine of the highest quality, with a very specific taste, then famous all over Georgia.

According to Vakhushti Bagrationi the border between mountains and valleys is delineated by wine. He says that the places where the vines bloom are called valleys, and where they do not, are mountains. In Kakheti, famous for its vineyards, wine is and used to be produced in the valleys. However, over time, the geography of wines and vineyards has changed dramatically.

The data of historical grape varieties throughout Georgia is impressive: sixty-six varieties are described in Kakheti. There were fifty-nine varieties in Guria, fifty-three in Samegrelo, and forty-eight local grape varieties in Abkhazia. Unfortunately, neither Guria, Samegrelo, nor Abkhazia are today considered wine regions. They were once famous for their winemaking traditions, but viticulture in these regions has declined over the last two centuries and has lost its importance in agriculture.

Wine harvest in Telavi. "Iveriel" Digital Library of the National Parliamentary Library of Georgia

Georgian viticulture and winemaking were endangered many times. Prolonged wars often forced the local population to leave, and even the vineyards that had been cultivated for years were overgrown. Even in relatively peaceful periods, the vineyards did not lack problems. In the 1880s, the problem of the grapevine pest, phylloxera, became especially acute. The attempt by Russian scientists to solve the problem by pouring chemicals into the roots of diseased vines did not succeed. Instead, Ioseb Guntsadze, a viticulturist and agronomist from Kvaliti (a village in Imereti, Zestaponi district) found a solution, and grafted the vines onto American rootstock, and the Georgian vines survived.

During the Soviet period, the scale of winemaking increased, and the quality of wine fell. Many unique varietals were forgotten, and, at the dictation of the state economic policy, the viticulturists were mainly engaged in the cultivation of three varieties (rkatsiteli, saperavi and tsolikauri).

In the 1990s, in the conditions of independent Georgia, the process began to restore Georgian winemaking traditions and produce unique wines. Such forgotten unique varieties were returned to the karmidamo (farmhouses) of viticulturists, such as: Usakhelouri in Lechkhumi; Ojaleshi, Egudzguri, and Chvitiluro in Samegrelo; Chkhaveri in Guria; Mtsvivani, Chitistvali, Kisi, and Khikhvi in Kakheti; Shavkapito (in Kartli), among others. A few years ago, Georgian kvevri wine, and the technology of making and aging wine in kvevri, were included in the list of intangible cultural monuments of the world by UNESCO. Currently, about five hundred varieties of grapes are grown in Georgia, and Georgian wine is slowly establishing its own unique niche in the world market.

References:

- 1. Chitaia, Giorgi. “Dzveli legendebi vazis k’ult’uris ts’armoshobis shesakheb” (Ancient legends on the origin of viticulture). Dzeglis megobari, no. 16 (1968): 9–

- 2.Chilashvili, Levan. Vazi, ghvino da kartveloba (Vines, wine, and Georgianness). Tbilisi: Petiti, 2004.

- 3. Lekiashvili, Andro. Shen khar venakhi (You are a vineyard). Tbilisi: Nakaduli, 1972., 37.

Cover image: The Gurgenidze family gathered by the winepress, 1935. "Iveriel" Digital Library of the National Parliamentary Library of Georgia.