Four nanas by Three Brothers

It is very likely that anyone interested in Georgian folk songs has sung or at least heard the Gurian song “Otkhi Nana” whose title roughly translates to “four nanas.”[1] This was the case with me. When I was a child, I learned the song from Valery Kutidze, director of the Ensemble Martve. Its lyrics tell the story of three brothers—Ladiko, Akvsenti, and Manase Salukvadze—who lost their bulls, Kamusha and Almasa.

For a long time, I believed these three brothers to be fictional characters. I thought there must have been a poem written about their troubles, and that the text was then used in the song “Otkhi Nana.” As it turns out, however, things were not so simple. In 2009, at a concert by the Anchiskhati choir, I heard a version of the song “Chven Mshvidoba” that significantly differed from the many other variants of the song I’d heard before. There was something melodically restless in this variant, which surprised the listener right from the start, in a pleasant, smile-inducing way. When introducing the song, the performers noted that the variant came from the brothers Ladiko, Akvsenti, and Manase Salukvadze. I was taken aback when I heard these names. This unique version of “Chven Mshvidoba” came from the same three brothers named in “Otkhi Nana”—a song, unlike “Chven Mshvidoba,” which is not particularly complex melodically. I wanted to hear the original audio recording of this variant, so I contacted a member of the Anchiskhati choir, Levan Veshapidze.

Veshapidze told me that the songs performed by the Salukvadze brothers were part of a newly released series wax-cylinder recordings.[2] I opened the disc containing materials from Shalva Mshvelidze’s 1931 expedition and found that the liner notes listed a whole series of songs performed by the “Brothers from Bakhvi”: “Otkhi Nana,” “Chven Mshvidoba,” “Madlobeli,” “Mravalzhamieri,” “Masp’indzelsa Mkhiarulsa,” “Akhali Shvidk’atsa,” “Mts’vanesa da Ukudosa,” and “P’at’ara Saq’varelo.”[3] All of these songs are characterized by a unique, signature style. The brothers’ melodic variants are wonderfully diverse, with all three voices moving constantly, leaving no space without melodic figuration. It is like walking a tight rope, although the Salukvadze brothers manage to navigate the most complex moves with ease.

Let us offer a recording of “Chven Mshvidoba” to further convince you:

The brothers Ladiko (1892–1963), Manase (1894–1964), and Akvsenti Salukvadze (1897–1970)were born in the village of Pampaleti, in the family of Besarion Salukvadze and Pilimon Intskirveli.[4] They also had an older brother, Ambrose, who, according to Manase’s grandson Gulnaz Mujiri, did not song, though he was a famous tamada. After Bessarion’s death, the four children were raised by their mother, Pilimon Intskirveli.[5] The brothers were famous woodworkers, who built houses and made a living through carpentry. They also pursued agriculture. The land in their village was not suitable for corn, so the brothers, like everyone else in the village, also had some cornfields in Lekiani, near the confluence of the Natanebi River and the Black Sea.

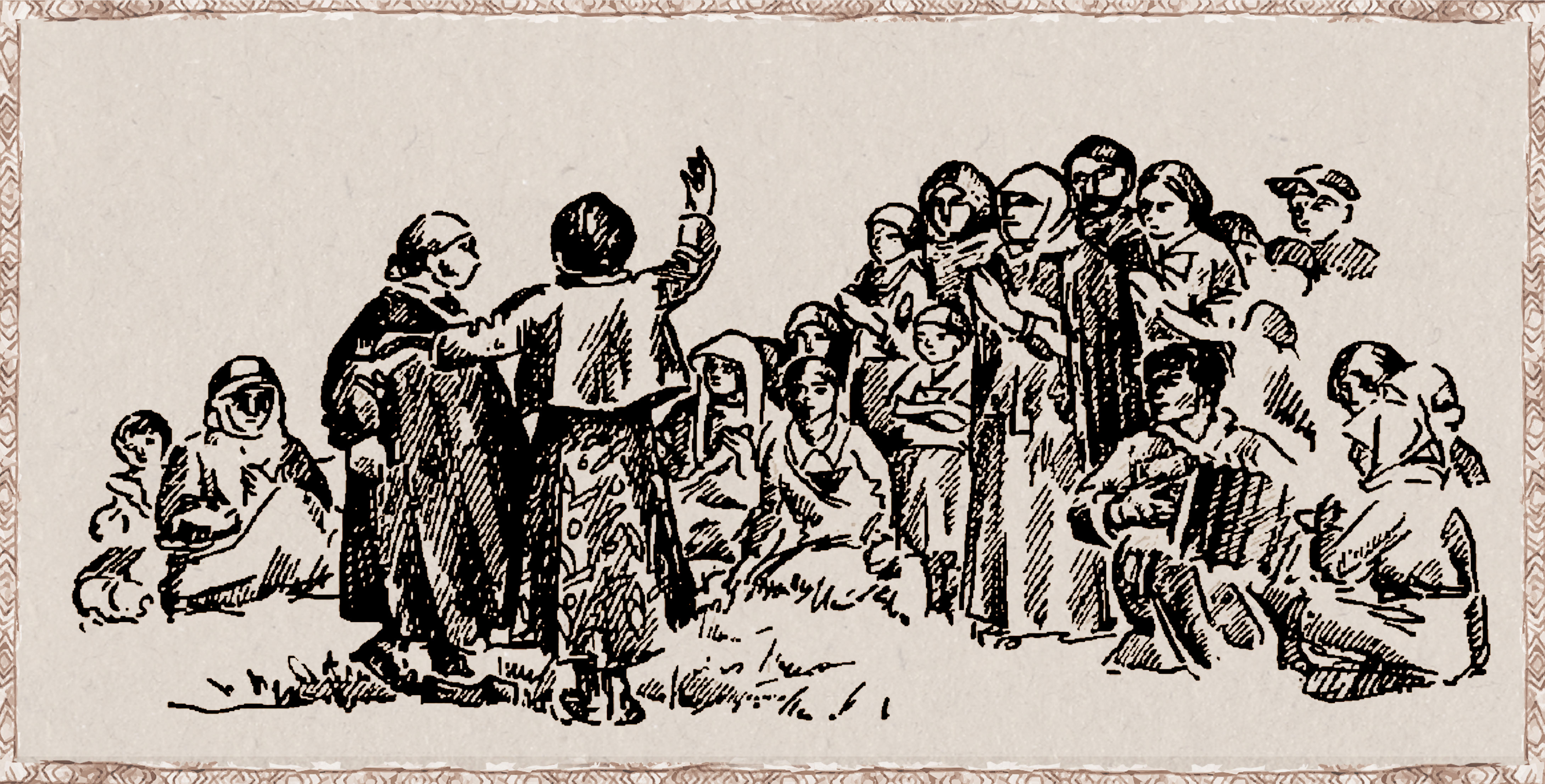

From left to right: Akvsenti, Manase and Ladiko Salukvadze

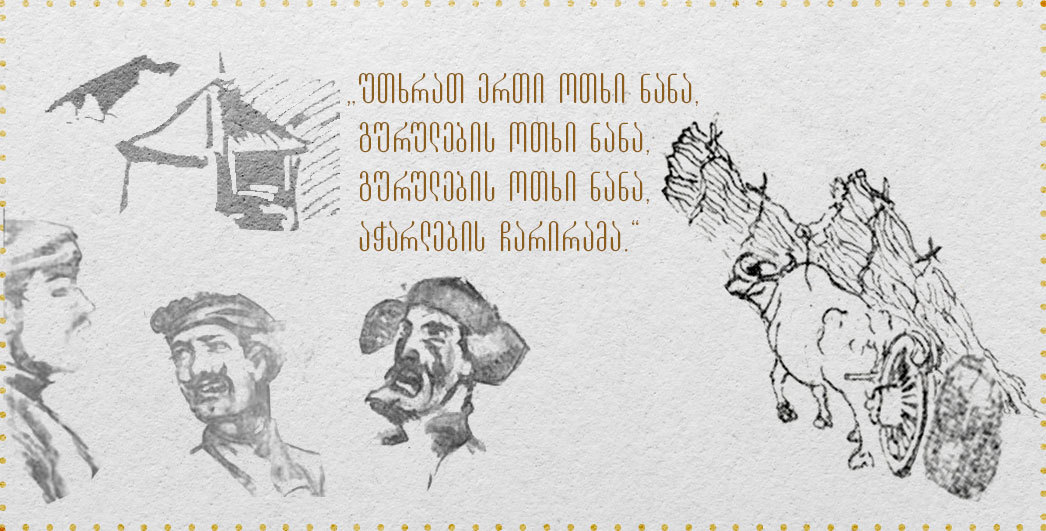

One day, the story goes, news spread in the village that the grain stores in Lekiani had been damaged due to heavy rains. The brothers yoked their oxen, Kamusha and Almasa, and rushed towards Lekiani to salvage what grain they could. On the way back, they ran into some friends, whose invitation they could not refuse. While waiting for their owners, Kamusha and Almasa, loaded with corn, started up again on their way. The oxen, however, did not follow the correct path, and they apparently fell into the river as it rushed towards the sea. Upon their return, the brothers found only bits of their broken cart in the river. There was nothing they could do, so on their way back home, they turned their story into a poem and adapted it to the tune of “Otkhi Nana.”

Many people think that “Otkhi Nana” was created by the Salukvadze brothers, because their version is the most popular. In actuality, this song has a longer history. According to the famous singer Simon Megrelishvili, the older lyrics of the song went as follows:

Let’s sing an Otkhi Nana,

Otkhi Nana of the Gurians,

Otkhi Nana of the Gurians,Charirama of the Ach’arans.[6]

The lyrics of the song have been changed many times. However, it gained real popularity after the Salukvadze brothers adapted the poem about the loss of their bulls in Lekiani. Here is a recording of their version of “Otkhi Nana,” recorded by Shalva Mshvelidze in 1931:

In 1918, the brothers enlisted in the People’s Army of Guria and Ach’ara, and, during a battle with the Ottoman army, Manase Salukvadze was wounded in his side. The Salukvadze brothers also participated in background and crowd scenes in Siko Dolidze’s 1936 film Dariko. In 1949 they took part in the Olympiad of amateur artists held in Tbilisi.

Bessarion Intskirveli was a famous singer from Pampaleti, who learned singing from the great masters of Gurian singing, Samuel Maksimelishvili and Data Gugunava. Bessarion was also a member of the choir led by Samuel Chavleishvili, known as the “nightingale” of Gurian song.

Sitting from left to right: Ladiko Salukvadze, unknownStanding: Akvsenti and Manase Salukvadze. Sandro Natadze's archive

While Bessarion Intskirveli undoubtedly had a significant influence on the musical development of the Salukvadze brothers, I would argue that their singing, versatility, and musical thinking still seem unique. The Salukvadzes’ style is distinctly their own, as further evidenced by the other Salukvadze songs recorded by Shalva Mshvelidze.

Based on archival materials, the Salukvadze brothers were recorded only a handful of times:

1) Shalva Mshvelidze’s 1931 expedition, during which Mshvelidze recorded eight songs (listed above).

2) Grigol Chkhikvadze’s expedition of 1933, when the brothers’ performances of “Chven Mshvidoba” and “Khasanbegura” were recorded.[7]

3) Grigol Kokeladze’s expedition, the year of which is unknown. From this expedition we have recordings of “Otkhi Nana”[8] and “Mts’vanesa da Ukudosa.”[9]

It is a pity that not many stories of the Salukvadze brothers have survived, although I hope to come across undiscovered new materials through my research. This research would not be possible without the assistance of a number of descendants of the Salukvadze brothers: Malkhaz Uturashvili, Gulnaz Mujir, Marina Oragvelidze, and Mzia Mamaladze. I thank them for their help and their valuable information.

[1] “Nana" in the context of songs may have different meanings such as: 'mother' (in Samegrelo), a vocative for "my child" (in Samegrelo), a cradle song, an exclamation to express surprise (in Samegrelo), a synonym for sleep, a vocable, glossolalia, etc. It is also known as an ancient Georgian female deity, the mother of deities, and one of the main hypostases of the sun.

[2] From 2006 to 2008, the Center for Traditional Polyphony at the Tbilisi State Conservatory digitized a large number of wax-cylinder recordings held in various institutions, museums and archives throughout Georgia. The series was known as

Echoes from the Past: Georgian Folk Music from Phonograph Wax Cylinders. The Salukvadze brothers’ recordings appear on Vol. 1 (2006), CD 4.

[3] The Salukvadze brothers were from the village of Pampaleti, which at the time was under the administration of the village Bakhvi. Because of this, they are commonly referred to as the Brothers from Bakhvi.

[4] Since I believed Pilimon was a man's name, I decided to double-check and was told that in this case, it is definitely a woman's name.

[5] History of the Song ‘Otkhi Nana’ Created by the Brothers from Bakhvi: Ladiko, Manase, and Avkesenti Salukvadze, a manuscript by Malkhaz Uturashvili, descendant of Manase Salukvadze.

[6] K’omunizmis gantiadi, July 18, 1972 (no. 85), p. 4.

[7] See the website folkcatalog.ge, which includes descriptions of the magnetic tapes in the audiovisual collections of the Georgian National Archives.

[8] Grigol Kokeladze, Asi kartuli khalkhuri simghera (One hundred Georgian folk songs) (Tbilisi: Khelovneba, 1984), 264.

[9] The list of recordings appears in the catalog in the archive of Tamar Mamaladze, which is located at the Institute of History and Ethnology and the State Folklore Center (catalog number T.M. 40_6). There was something that confused me here: if the recordings were Kokeladze's, why are they in Mamaladze's archive? I came across the catalog in Mamaladze’s archive, and while only “Otkhi Nana” is mentioned in Kokeladze's edition, Mamaladze’s also references “Mts’vanesa and Ukudosa.”

%20%E1%83%A1%E1%83%90%E1%83%9C%E1%83%93%E1%83%A0%E1%83%9D%20%E1%83%9C%E1%83%90%E1%83%97%E1%83%90%E1%83%AB%E1%83%94%20-%20%E1%83%9E%E1%83%A0%E1%83%9D%E1%83%94%E1%83%A5%E1%83%A2%E1%83%98%E1%83%A1%20%E1%83%AE%E1%83%94%E1%83%9A%E1%83%9B%E1%83%AB%E1%83%A6%E1%83%95%E1%83%90%E1%83%9C%E1%83%94%E1%83%9A%E1%83%98%2C%20%E1%83%A1%E1%83%90%E1%83%A0%E1%83%94%E1%83%93%E1%83%90%E1%83%A5%E1%83%AA%E1%83%98%E1%83%9D%20%E1%83%A1%E1%83%90%E1%83%91%E1%83%AD%E1%83%9D%E1%83%A1%20%E1%83%AC%E1%83%94%E1%83%95%E1%83%A0%E1%83%98-min.jpg)