Traditional Music of Soviet Georgia

Introduction

The young cadets of the First Republic of Georgia, who, in those ill-fated days of February,[1] fought against the advancing Red Army from Russia, encouraged each other with patriotic Georgian folk songs.[2] They likely had no idea that, in the following years, the blood of thousands of Georgians would be shed in the struggle for freedom, with countless citizens forced to flee their homeland. Churches and monasteries would be destroyed, worship services and chants would be banned, and the Catholicos-Patriarch of Georgia would be arrested. Prominent members of Georgian society would face execution. Meanwhile, amid all this turmoil, they poured out sycophantic praises and sang together in praise of Soviet leaders, communism, the Red Army, and the heroes of socialist labour — the joyful tractor drivers, tea workers, and silkworm breeders.

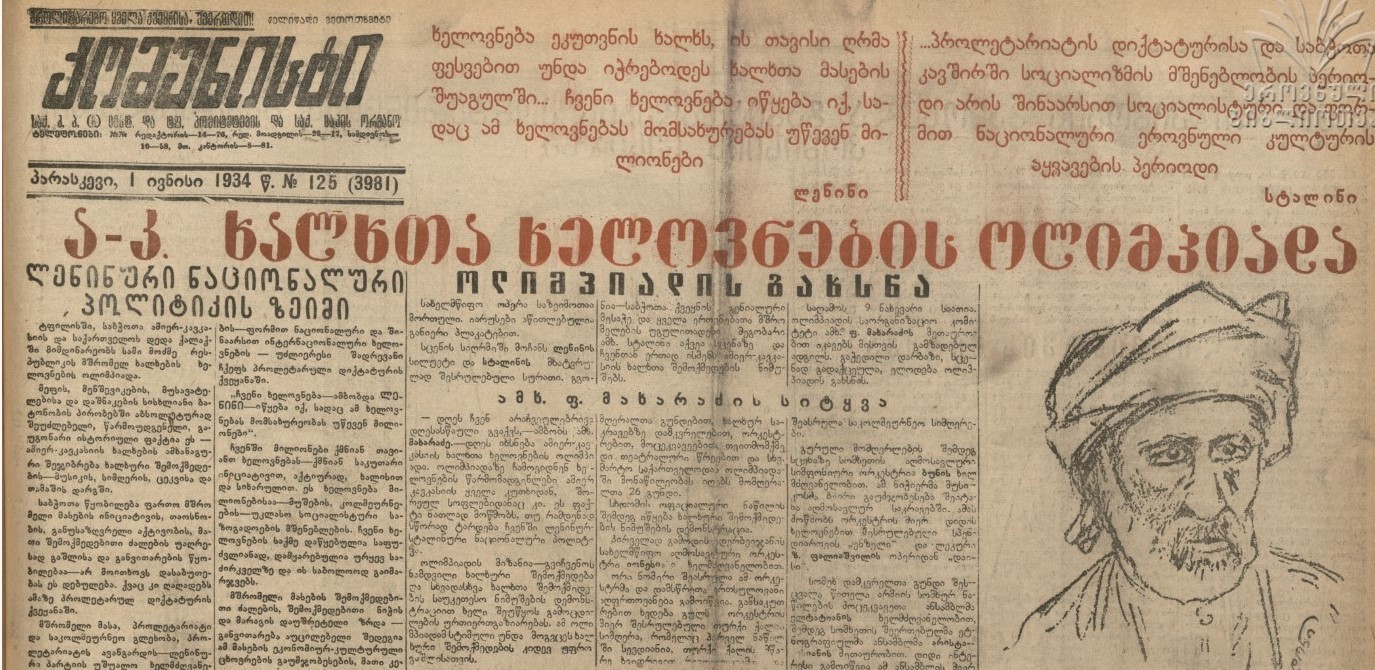

It is part of the nature of totalitarian regimes to organise masses of people through propaganda and terror, convincing them of a common goal. In the years following the October Revolution, amidst an aggressive policy targeting various institutions and social strata, as well as the consolidation of its own power, the Soviet government placed great emphasis on using culture as an instrument of propaganda. It is well-known that Stalin referred to Soviet writers as “engineers of the human soul.” [3] According to his plan, art, cinema, and music—including folk music—were to educate and shape the “New Soviet Man,” [4] and they were expected to be “national in form and socialist in content. ” [5] Thus, during the years of Stalin's rule, this led to the creation of a new layer of Georgian traditional music, now known as ‘Soviet Folklore.’ In 1934, during the Art Olympiad of the Peoples of Transcaucasia held in Tbilisi, the newspaper Komunisti [The Communist] reported as evidence of the successful implementation of art that was “national in form and socialist in content”: “The motifs of folk art have changed. The flute sighs in a new way, the Ashug sings in a new way, the victorious worker dances in a new way... A new life is created, a new man arrives, with a new song, new music, and new folk art.” [6]

1934, No. 125.

Folklore in the Service of Propaganda

The tendency to use folklore as a tool for propaganda became particularly prominent in the 1930s. It is well-known that potential creators of modern Soviet folklore were strategically provided with magazines and newspapers, radios at home, invited to major cities, briefed on the achievements of Soviet art, and lectured on improving their moral and political views.[7] Lyricists and composers working in the Soviet republics were tasked with creating new songs based on folk motifs that depicted Soviet life. These songs, following the principles of the sole creative method allowed at the time—socialist realism—had to be imbued with socialist content, easy to understand and remember, and filled with a solemn, optimistic tone.

Initially, composers were not enthusiastic about such directives, but over time, creating songs inspired by the new reality became a desirable pursuit. As these songs were frequently featured in radio broadcasts and concert programs, and due to the high regard for their authors' work, many enthusiasts were drawn to this activity. The 1930s in Georgia were marked not only by the rise of ‘new folklore’ but also by the establishment of organisations[8] dedicated to folk art and large-scale folklore events.[9]

Salami Shen Kolmeurnev. Recorded by Vladimer Akhobadze in Adjara in 1958. In the audio album: Georgian Soviet Folk Songs. Compiled by Otar Kapanadze. Tbilisi State Conservatory. 2018.

Song about Lenin. Recorded by Vladimer Akhobadze in Adjara in 1958. In the audio album: Georgian Soviet Folk Songs. Compiled by Otar Kapanadze. Tbilisi State Conservatory. 2018.

Stalin and the Dekada of Georgian Art

In 1937, a Dekada [10] of Georgian Art was held in Moscow as part of a broader series of cultural events. Between 1936 and 1941, ten such dekadas of art from various Socialist Republics took place in the Soviet Union’s capital. These events served a dual purpose: on the one hand, they were used to promote the political ideology of the Stalinist era, while on the other hand, they provided an opportunity for the republics to showcase and share their cultural achievements. The Dekada of Georgian Art inspired a sense of national pride within Georgian society, and much was written and said about the reception of participants in the Kremlin, including performers of Georgian folk songs and dances, and their meeting with Stalin.

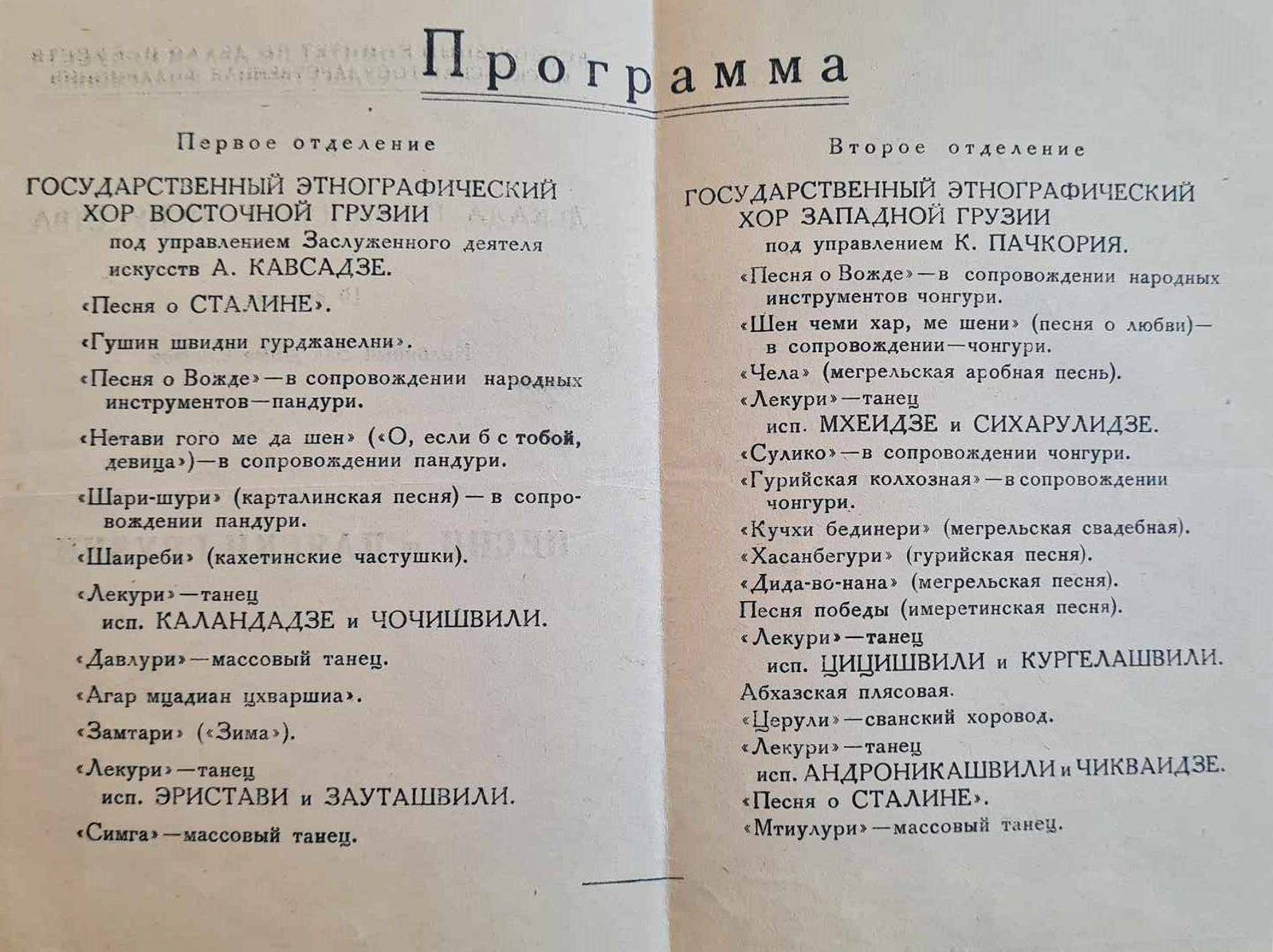

On January 18, ethnographic groups from Eastern and Western Georgia performed traditional Georgian music and dances before an audience at Moscow's renowned House of the Unions. Four songs in the concert were dedicated to the leader of the Soviet Union. The program included popular shairs [11], romantic duets, and lyrical songs of the time, mostly with instrumental accompaniment. Against the backdrop of these straightforward, easily comprehensible pieces, songs that showcased the uniqueness of Georgian traditional music — highlighting the variety of polyphonic forms and performance styles — occupied a more modest place in the program.

Program of the Decade of Georgian Art folklore concert held in Moscow in 1937.

First part. State Ethnographic Ensemble of Eastern Georgia directed by A. Kavsadze: Song about Stalin, Gushin shvidni gurjanelni, Song about the Leader (with panduri accompaniment), Netavi gogo me da shen (with panduri accompaniment), Shairebi, Lekuri (dance. performed by Kalandadze and Chochishvili), Davluri (mass dance), Agar mtsadian tskhvarishia, Zamtari, Lekuri (dance. performed by Eristavi and Zautashvili), Simga (mass dance). Second section. State Ethnographic Ensemble of Western Georgia directed by Kirile Pachkoria: Song about the Leader (with chonguri accompaniment), Shen chemi khar, me sheni (with chonguri accompaniment), Chela, Lekuri (dance. performed by Mkheidze and Sikharulidze), Suliko (with chonguri accompaniment), Gurian Sakolmeurneo (with chonguri accompaniment), Kuchkhi Bedineri, Khasanbegura, Didavoi Nana, Victory song, Lekuri (dance. performed by Tsitsishvili and Kurgelashvili), Abkhazian Dance, Tseruli, Lekuri (dance. performed by Andronikashvili and Chikvaidze), Song about Stalin, Mtiuluri (mass dance).

Books about Stalin often mention his musical skills. In this regard, one account from the memoirs of actor Akaki Vasadze, describing a visit by his childhood friends and Georgian actors to Stalin's government dacha in Sochi in 1946, is especially notable. [12] According to Vasadze, when they started singing Mravalzhamier around the dinner table, Stalin first sang the top voice, then the middle voice. This was followed by Gushin Shvidni Gurjanelni and Gaprindi Shavo Mertskhalo. [13] Then Stalin asked Vasadze to sing the Gurian song Khelhvavi. The actor writes: 'When I began the first verse, Stalin stopped me and said, “This is wrong... I think the first line should start like this,” and he sang it himself. When he finished singing the last two bars with “კრინი” (k'rini — a high and very thin-voiced singing style), I remembered in time who performed the Gurian Khelhvavi this way, and exclaimed, “This is Chavleishvili's version!”

As it turned out during the supra, the future leader of the Soviet Union had learned Chavleishvili's versions of the Gurian songs from Gurian prisoners in the Kutaisi prison when he was still a young revolutionary.[14]

Is it difficult to discern when his emotions were sincere? Was it when he joyfully sang Mravalzhamier or Khelkhvavi with the friends of his youth, or when he gave ovations to songs celebrating the leaders and heroes of socialist labour, which had entirely different content and aesthetics?

Regarding the dekada, one more thing should be mentioned. Before the trip to Moscow, several members of the East Georgian ethnographic choir, specifically a group of singers from the village of Kakabeti, led by Mikha Jighauri, were arrested. According to accounts, during the reception following the concert, choir leader Sandro Kavsadze informed Stalin about the singers' imprisonment. Reportedly, following Stalin's orders, the singers were released that same night.[15] However, this is not what actually happened. Although Mikha Jighauri and members of his group—Vano and Sandro Mchedlishvili—were indeed released from prison soon after, personal files of two other members of Jighauri's ensemble, Zakaria Mchedlishvili and Giorgi Gulnazarov, found in the list of Stalin-era repressions, reveal a different reality. [16] In fact, Zakaria Mchedlishvili, a former member of the East Georgian ethnographic ensemble, was sentenced to confiscation of personal property and 10 years of imprisonment by the USSR Supreme Military Collegium's itinerant session for Trotskyist-Menshevik activities. Giorgi Gulnazarov, on similar charges, was executed.

Amateur Creativity in the Soviet Union

Beginning in the 1930s, as part of the Soviet government's strategy to use culture and art, including folk art, as an instrument of ideological propaganda, state-funded so-called ‘amateur ensembles’ appeared in Georgia. These folk choirs were affiliated with various institutions and enterprises, including automobile and tractor factories, canneries, yarn and leather-shoe factories, housing authorities, labour reserves, railway depots, flour mills, trade departments, and others.

In the Soviet Union, the terms ‘amateur’ and ‘amateur creativity / art’ referred not to independent or self-organised activities, but to non-professional and hobbyist endeavours. Engaging in activities independently of the government could be risky for amateur ensembles during the Stalin era. For example, it is documented in the files of the People's Commissariat of Education that in the 1930s, Maro Tarkhnishvili's choir independently organised folklore concerts in clubs across Tbilisi and other regions. This unauthorised initiative led to the head of the Music Department of the Department of Artistic Performances considering strict supervision over the ensemble. In the case of non-compliance with instructions, the group would be subject to being labeled as a ‘wild artel’ (unauthorized collective). [17]

The creativity of amateur groups—their repertoire and performance style—was regularly evaluated at the Republican Folklore Olympiads, which are also another legacy of the Soviet era. On the one hand, such events helped increase the visibility and activity of folklore groups; on the other hand, they stimulated debates about the ‘good’ and ‘bad,’ ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ performance of folklore. The prospects of receiving funding and awards, as well as the risk of losing them, often led to unhealthy competition among choirmasters.

Afterword

Since the 1960s, traditional music performance has undergone significant changes. Gradually, previously forbidden church chants and other forgotten genres began to be performed on stage. However, over the decades, the use of folk music as a propaganda tool, its transformation into a part of culture that was “national in form, socialist in content,” and the growing popularity of modern folk songs led to society’s indifference and lack of interest—particularly among the younger generation—in the old, authentic forms of traditional music.

Ethnomusicologist Tamar Mamaladze, in her report on research conducted in 1967 in Racha and Lechkhumi, writes: “ The promotion and care of folk music seem to have become a state affair, but on the contrary, this treasure of ours is almost slipping away... There is a sense of disenchantment with the old songs in the villages. Young people are captivated by love songs. They pay no attention to those who still remember their regional songs.” [18]

The fact is that the Soviet government, on the one hand, supported folklore by funding numerous ensembles, large-scale events, and research institutes, while on the other hand, using it as a propaganda tool. It should also be noted that, despite ideological pressure, in some cases choirmasters and singers managed to showcase their talents and abilities, or, as ethnomusicologist Edisher Garaqanidze put it, “the emanation of primary folklore.” [19] Ultimately, whether the 70-year Soviet era did more good or harm to this area of Georgian culture remains a subject of debate. There is no substitute for studying audio, visual, and manuscript archival documents to obtain objective answers to these various questions.

[1] This refers to the occupation of Georgia by Russia in 1921.

[2] Matikashvili, Nikoloz. 1990. Iunk'rebi [Cadets]. Tbilisi: Metsniereba

[3] Nemsadze, Ada. 2023. "The Renewed Tsiskari and the End of Socialist Realist Criticism." Contemporary Issues of Literary Studies Vol. 16: XVI International Symposium Contemporary Issues of Literary Criticism Socialist Realism in Literature and Art, 411-419. https://cils.openjournals.ge/index.php/cils/article/view/7577.

[4] This definition of Soviet culture belongs to Stalin. In 1930, at the XVI Congress of the Communist Party, he stated that socialism, which has as its ultimate goal the dictatorship of the proletariat and the fusion of nations (and thus national cultures), still has a long way to go. Before the fusion into a common culture, the development of national cultures and the full revelation of their potential were necessary. He noted that a culture that was national in form but bourgeois in content served to poison the masses with nationalism and strengthen the bourgeoisie; on the other hand, a culture that was national in form but socialist in content was to educate the masses in the spirit of socialism and internationalism. (Stalin, I.V. 1951. Zaklyuchitel'noye slovo po politicheskomu otchetu TSK XVI s"yezdu VKP(b) 2 iyulya 1930 g. [Political Report of the Central Committee to the XVI Congress of the VKP(b), June 27, 1930] in Sochineniya [Works], Vol. 13. Moscow: State Publishing House of Political Literature. pp. 1-16. See https://www.marxists.org/russkij/stalin/t12/t12_21.htm.)

[5] Levanidze, Maia. 2020. "Mtsirepilmianobis" p'eriodis Mok'rdzalebeli Khibli (A Modest Charm of the "Movie Shortage" Period). In Sakhelovnebo Metnsierebata Dziebani (Art Sciences Studies) #2 (83), 20–25, 168-169. Tbilisi: Shota Rustaveli Theatre and Film State University of Georgia. https://dziebani.tafu.edu.ge/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Art-Science-Studies-2-83-2020-1.pdf

[6] “Leninuri natsionaluri p'olit'k'is zeimi” [Leninist National Policy Celebration] K'omunist'i, No. 125: p1, 1934.

[7] Miller, Frank. 2006. Stalinskii fol'klor. St. Petersburg: DNK, 18. Originally published in English as:

Miller, Frank. 1992. Folklore for Stalin: Russian Folklore and Pseudo-folklore of the Stalin Era. Routledge.

[8] In 1932, the Department of Folklore was established at the Georgian National Museum, which later became the foundation for the Department of Folklore and Archive at the Shota Rustaveli Institute of Georgian Literature. In 1935, the Folk Music Cabinet was formed at the Tbilisi Conservatory. In 1936, the Folk Art Cabinet was established under the Administration of Arts Affairs, which was soon converted into the Republican House of Folk Art. The Caucasian Historical-Archaeological Institute (now the Institute of History and Ethnology) underwent reorganization in 1931 and 1936. Folklore studies became one of the priorities in the Faculty of Humanities at Tbilisi University and other higher educational institutions in Georgian cities.

[9] In 1934, the Art Olympiad of the Peoples of Transcaucasia was held in Tbilisi, with hundreds of ensembles and individual performers from the three republics of Transcaucasia participating. Republican Olympiads were held in 1936 and 1938. A significant event was the Georgian Art Dekada held in Moscow in 1937, where folk song and dance occupied an important place.

[10] The term dekada here means a period of time - originally ten days - devoted to a socially (and culturally) significant event. In this example, in January 1937, a Dekada of Georgian Art was held in Moscow, which included performances, exhibitions and film screenings of Georgian art achievements.

[11] The term shairi is of Arabic origin. In a broad sense, it denotes a poem as a whole. In folk art, it refers to a poem or song in a humorous, improvisational style, often performed by name. A popular form of musical performance, it has a long tradition in Khevsureti and Pshavi, where shairi of different content are often sung to the same tune. However, it is worth noting that the term shairi is also found in the mourning genre, such as Zrunis shairi or Mtibluri shairi, which were common in Racha.

[12] Vasadze, Ak'ak'i. 2012. Shekhvedra St'alintan [Meeting with Stalin]. Tbilisi: Art'anuji.

[13] Ibid., pp. 22, 25.

[14] Ibid., p. 26

[15] Asieshvili, Baia. 2007. K'avsadzeebi. Tbilisi: State Folklore Centre of Georgia.

[16] Mchedlishvili, Ioseb. 2008. Mikha Jighauris Gundi [Mikha Jighauri's Choir]. Tbilisi: State Folklore Centre of Georgia.

[17] Central Archive of the Recent History of the National Archive of Georgia. Department of Arts of the People's Commissariat of Education of the Georgian SSR. Fund #181, Series 1, File #468.

[18] Mamaladze, Tamar. 1969. Rach'asa da Lechkhumshi miekveq'neba angarishi [Report on the 1969 Fieldwork in Racha and Lechkhumi]. Archive of the Ivane Javakhishvili Institute of History and Ethnology. Tamar Mamaladze Fund, Folder #14, Notebook VI.

[19] Garaqanidze, Edisher. 2007. Kartuli Khalkhuri Simgheris Shemsrulebloba (Performance of Georgian Folk Song). Tbilisi: Intellekti.

%20%E1%83%97%E1%83%94%E1%83%9D%E1%83%9C%E1%83%90%20%E1%83%A0%E1%83%A3%E1%83%AE%E1%83%90%E1%83%AB%E1%83%94%20-%20%E1%83%A1%E1%83%90%E1%83%A0%E1%83%94%E1%83%93%E1%83%90%E1%83%A5%E1%83%AA%E1%83%98%E1%83%9D%20%E1%83%A1%E1%83%90%E1%83%91%E1%83%AD%E1%83%9D%E1%83%A1%20%E1%83%AC%E1%83%94%E1%83%95%E1%83%A0%E1%83%98-min.jpg)