The Soviet Christmas Tree and Santa Claus — A symbol of Children's joy or a Means of Manipulation

In 1926, the Akhali Sopeli [New Village] magazine published a somewhat strange poem, titled "Do not cut down the forests", which has since then become well-known in our society.[1]

Do not cut down the forests, brother, the mountains will grow bare.

Violets and roses will freeze, the wind will rip out their roots.

Save the forest for your children, it is your duty as a father.

Or storms will erode the mountaintops down to naked rock.

The cold alpine springs will dry up, the locusts will devour your crops

There will be no more timber for you, no matter how hard you look.

The strong west wind will blow you away.

Take care of the forest, brother, it will always protect you,

Do not be its enemy — treat it with love

Don't leave your children to deal with your sins, open your eyes.[2]

Nowadays, this poem is included in the folk poetry section of school textbooks, and children study it as a folk poem. Moreover, for a long time, the majority of ecological projects implemented by the public school system have been carried out under the mottos of "Don't cut down the forests!" or "Save the forest for your children!" The poem is often attributed to Vazha-Pshavela. Vazha-Pshavela is likewise named as the author of the lyrics to the song by Revaz Laghidze set to this text.

However, few people know that the author of the poem was a forester named Vaso Aptsiauri from the village of Khopisi, in the Tetritskaro district. We know that during his childhood he spent some time as a shepherd in the village of Namtvriani; then Vazha-Pshavela (1861-1915) took him to the school in Toneti, taught him to read and write and made him fall in love with poetry. For the second time, this poem was printed with the author's surname again in 1927 in the collection "Forest Day" published by the People's Agricultural Commission of Georgia. Then it seems to have spread orally among the people, and in this oral transmission the poem lost its author and became anonymous. V. Aptsiauri has written a number of poems on forest themes, but unlike his other pieces, "Do not cut down the forests" soon gained popularity, inspiring many folk versions, written by folklorists in different parts of Georgia at different times.

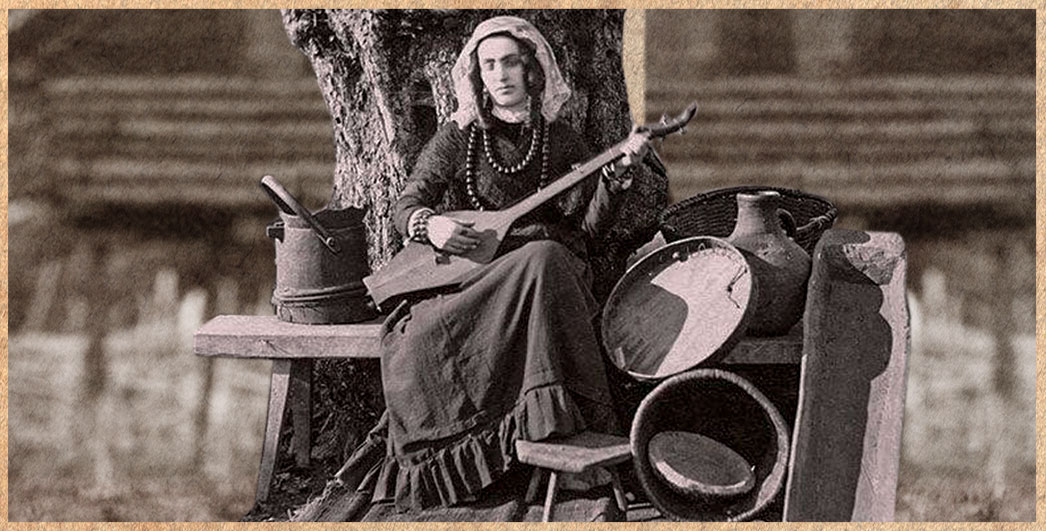

Soviet anti-religious propaganda poster, 1930, author unknown. Source: State Historical Museum of Russia.

This poem gives us a rare opportunity to follow the process of popularization of a text, which, in folklores studies, is not often possible. In particular: a) we know the author of the poem with certainty; b) over time, the poem became popular and acquired variants; c) in the process of folklorization, the identity of the individual author was lost, and the text became anonymous; d) the poem was completely adapted to the Soviet propaganda and the political context that prevailed in Georgia since 1921.

The 1920s were a period when the newly created multinational and multicultural Soviet Union started to create a new world order. This new reality did not include coexistence with the traditional social structures, lifestyle, and culture of the newly incorporated nations; it resisted everything that was connected to the past. Since religion was an integral part of traditional existence, some of the main targets of the Bolsheviks were religious holidays, worship artifacts, and clergy.

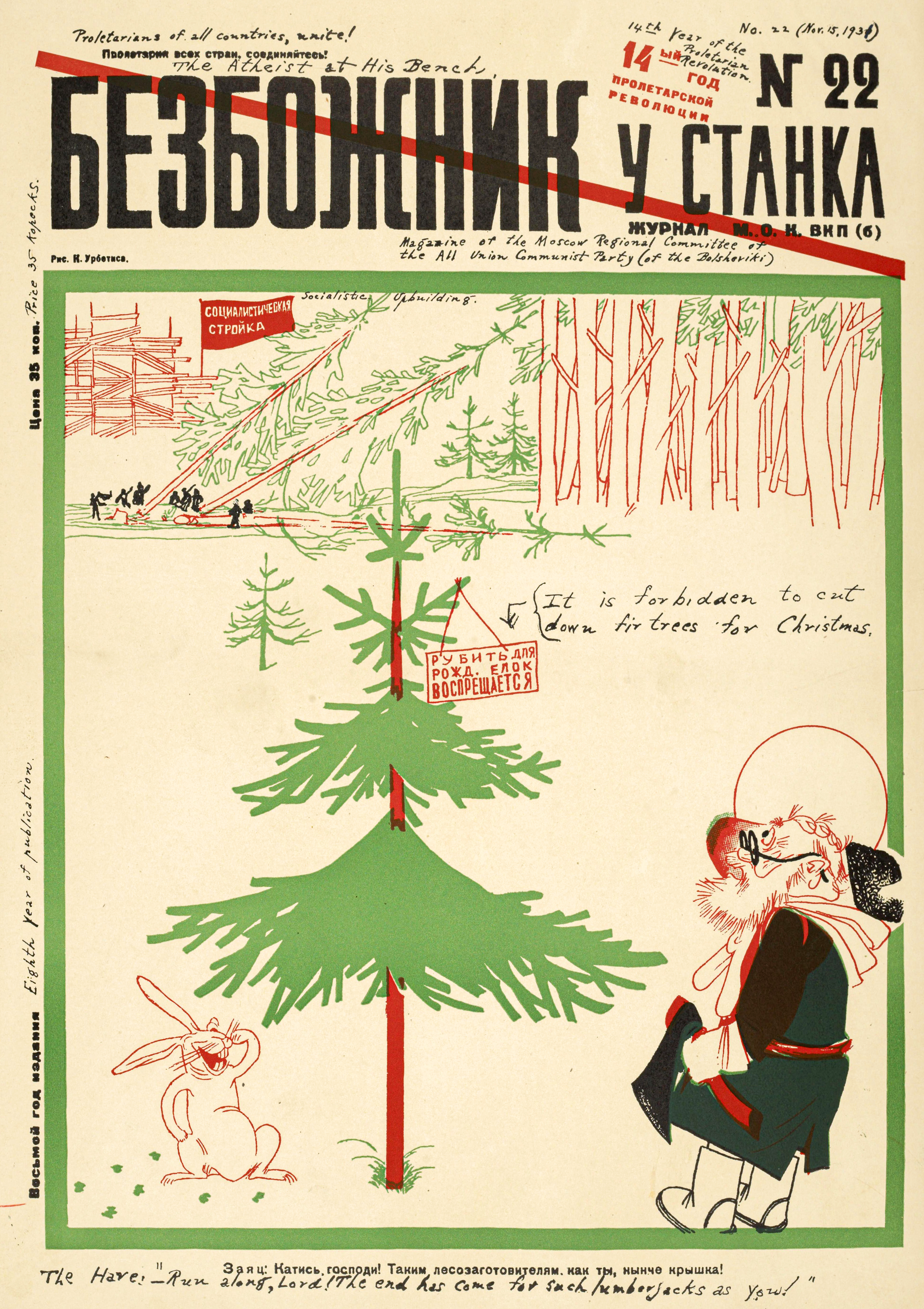

Since November 1922, the state organized anti-clergy youth marches. During these noisy anti-religious rallies, the communists were not satisfied with just insulting the clergy and called on people to replace the “church Christmas” with a "communist Christmas," and to declare January 7 as "the day of the overthrow of the gods." The people, who had once supported the overthrow of the monarchy and the oppression of the nobility, were disillusioned with the decline of traditional faith and religion and offered some resistance to radical atheism. Since 1923, the periodical edition of the Russian propaganda magazine "Ungodly Machine" (Безбожник у станка) further intensified the conflict. The editors of the magazine aimed to declare any religious affiliation as a sign of psychological problems and mental retardation, ridicule and put down not only the clergy and religious holidays, but also Christ, Muhammad, Yahweh, as well as the folk deities and mythological creatures. The Central Committee of the Soviet Union soon realized that the struggle against folk beliefs and traditions could was by no means perfunctory and was to be carried out systematically and with all seriousness, so that Bolshevism could penetrate into every nook and cranny of the country. In November 1924, the publishing of a bi-weekly humor supplement of the "Mushi" newspaper in the form of "Tartarozi" magazine, which was actually a translation of the anti-religious propaganda going on in Russia, began to be published in Georgia. This was soon followed by the establishment of the "Union of Fighters Against Divinity" in Moscow in 1925, with a Tbilisi branch opening in 1928.

From 1924, the Christmas tree, as a "religious relic" associated with the bourgeoisie, was blacklisted, along with the “Santa Claus”-like character of Grandpa Frost (Дед Мороз), the latter on the grounds of him being an avatar of the Russian folk demonological character, Morozko. Volunteer workers were assigned to go door to door to check if anyone had a Christmas tree. Putting up was Christmas trees in schools and kindergartens was forbidden. From the memoirs of the Russian communists, we learn that teachers were instructed to visit and inspect children’s homes at Christmas, and then to fine their parents.

From 1924, in the November-December editions of the children's magazines of the time, propaganda how harmful Christmas trees were for children was presented in the context of the cruelty of the act of cutting down Christmas trees. The connection with the old traditions of the Christmas tree was also periodically brought up, as in Ioseb Grishashvili's New Year's poem:

True, in this room

The green Christmas tree does not shine -

That's because we don't follow

Old rules and old customs.[3]

The Soviet government made ecology the main argument for the Christmas tree bans. Deprived of any sacred meaning, wood was designated for consumer building and industrial purposes. The issue of forest sacralization was overshadowed by its ecological significance, and a deliberate struggle against cutting down trees and forest destruction began. That is why the above-mentioned poem "Don't cut down the forests" resonated so well with the Soviet propaganda.

Front page of the magazine Godless at the Lathe, 1931.

When the ban on the Christmas tree in the anti-religious propaganda of the Soviet Union reached its climax (1928-1929), the People's Commissariat of Agriculture presented this verse to the government and the Anti-Divinity Union — the ritual object of the tree now devoid of any sacred meaning in people's consciousness, allowing only a narrow, utilitarian significance. At the same time, again and again, for propaganda purposes, it was very convenient for the poem by a poet who came from “the people” to be cut off from its creator and to be presented not as one author’s work, but as a piece of folklore of collective origin, which expressed the opinion not just of one individual, but the "voice of the people."

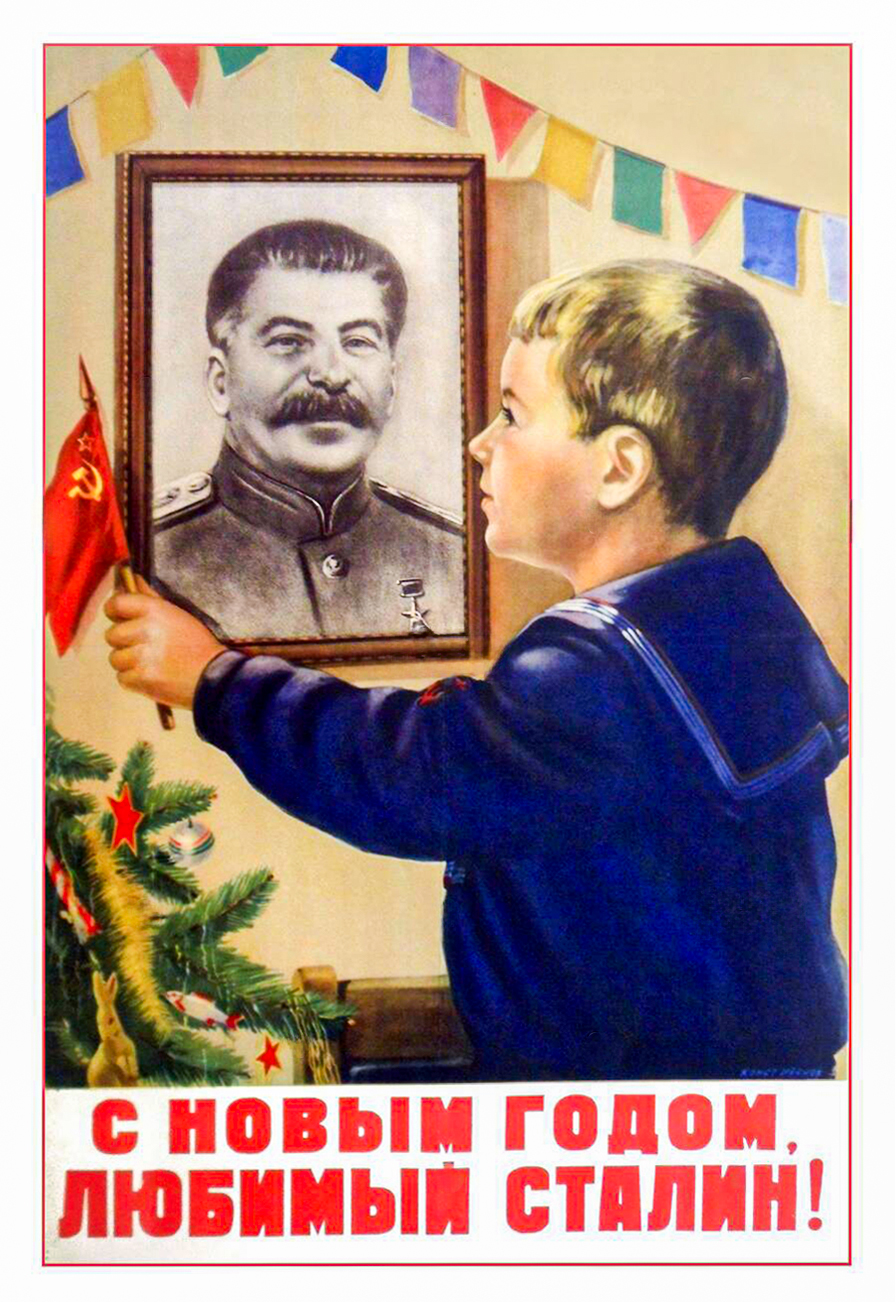

Later, at the end of 1935 [4], the Soviet authorities apparently realized the need for public holidays for the people, especially children, and decided to rehabilitate the repressed Christmas tree, but this time not for Christmas, but as the main attribute of the New Year’s holiday. To cut a long story short, the entire Soviet Union entered January 1, 1936 with decorated Christmas trees. This event was preceded by a letter of Pavel Postyshev (First Secretary of the Ukrainian Bolsheviks), in the December 28, 1935 issue of the Pravda newspaper. The author of the letter urged his fellow citizens to put up and decorate trees for the children for the New Year’s celebration. The discourse of the letter is based on highlighting the difference between the Christmas tree of the imperial period (when only the children of the bourgeoisie had the opportunity to enjoy it, and the children of the workers and peasants looked at them from afar) and the collective tree of the proletariat, when all children could experience Christmas trees. The author called on the leaders of the pioneers and members of the Komsomol to put up "Soviet New Year’s trees" in all schools and gardens, pioneer palaces, and children's cinemas on New Year's Eve.

In the process of cutting down New Year’s trees on the Union scale, everyone forgot about ecology. The trees were placed not only in children's and youth centers, but even in places where just a few years prior such things were heavily ridiculed and shunned and considered signs of "underdevelopment" and "weakness". In a word, the New Year’s tree was accepted into the party, and with it, the main character associated with the holiday — “Grandpa Frost”.[5] The Russian Morozko had as many façades as there were republics that were part of the Soviet Union at that time. So, for example, the Georgian tovlis babua was dressed in a white chokha-akhalukhi, with a white nabadi cloak and a saddle-bag.[6] Armenian or Uzbek Grandpa Frosts, who were also dressed in their national clothes, were completely different from him. All nations had to subscribe to the shared idea of the secular Grandpa Frost based on Russian folklore, with the legal “permission” to make ethnic/cultural adjustments in order to make him more relatable for the local people.

Thus, Stalin first took away and then returned to the Soviet children the Christmas (or rather, New Year’s) tree and a “Santa Claus” full of kindness, beloved and eagerly awaited by everyone. In of the Communist newspaper from January 3, 1936, V. Matsaberidze reported that in Tbilisi students’ celebrations with the New Year's tree were already underway on the evening of December 31, 1935. A local school principal thanked Comrade Stalin "for a happy and joyful life", alongside "children's best friend" Pavel Postyshev, and the leader of the Caucasian Bolsheviks - Lavrenti Beria. In his opening remarks he repeated Pavel Postyshev’s words juxtaposing the bourgeois and Soviet Christmas tree.

Over the course of the last two years, I interviewed about two hundred students born in different parts of Georgia between 2003 and 2005. For absolutely everyone, the tree is associated with New Year’s, not Christmas. Perhaps, in the history of the Soviet Union, it is difficult to find such a "successful" and still-existing public project as the New Year's tree. The Christmas tree became the object of manipulation by the Soviet authorities twice: it was first deemed necessary to ban due to anti-religious considerations, and but when it proved otherwise useful, it was brought back for the sake of public celebration and spectacle.

Soviet New Year poster 1952, by K. Ivanov. Source: National Library of Georgia

Magazines and newspapers from January 1936 were covered with photos of New Year’s trees and Joseph Stalin's powerful motto: "Comrades, life has become better, life has become happier!" Whether they were in the mood or not, everyone was forced to repeat the Soviet metanarrative, to follow the voice of the era. Few things so clearly illustrate the Bolsheviks’ attitude to people and things, their play on human emotions, than this double manipulation of the Christmas tree. Perhaps due to this duality or the irony of fate, Pavel Postyshev, who, in 1936 was hailed as the "best friend of children", became one of the victims of the Stalinist repressions of 1937. In 1939, Stalin's loyal associate Postyshev was shot on charges of Japanese espionage and Trotskyism.

Vaso Aptsiauri, a folk poet inspired by the love of the forest, could not have predicted, when he wrote this lovely poem, that his work, whether with or without his knowledge, would become a tool of Soviet propaganda. At that time and space, the ecology of personal space was a much more difficult task than taking care of the ecology of the forest.

Likewise, Vaso Aptsiauri could not have imagined that over time his poem would lose its author, and 100 years later it would appear in the folklore section of school textbooks as a brilliant example of anonymous folk creativity.

[1] For the extensive, academic version of this article, see:

Intskirveli, Eter. “Khis k’ult’is sek’ularizatsiis sak’itkhi sabch’oetis gamotsdilebashi”[“The Issue of Secularization of Tree-cults in the Soviet experience.” Pilologiuri dziebani [Philological research], VIII/2024. Gori. p. 268-283. http://www.sciencejournals.ge/index.php/NJ/article/view/552/495

[2] Aptsiauri, Vaso. “T’q’eebs nu schekhav” [“Do not cut down forests.”] Akhali Sopeli [New Village] Monthly Agricultural Journal, No. 4/March 1926, p. 16. Tbilisi.

[3] Grishashvili, Ioseb. “Unadzvod” [“Without a Christmas Tree”] Nak’aduli Journal No. 11-12/1925, p. 2.

[4] The Santa Claus-like character is called tovlis babua in Georgian (literally “snow grandpa,” which can refer to a snowman and a Santa Claus/Father Christmas type character) and Ded Moroz (Grandfather Frost) in Russian (coming from the folk character “Morozko”, “moroz” meaning “frost” in Russian). Because the character was most frequently referred to as “Grandpa Frost” throughout the Soviet Union, I have chosen to use that translation when mentioning him here.

[5] The Santa Claus-like character is called tovlis babua in Georgian (literally “snow grandpa,” which can refer to a snowman and a Santa Claus/Father Christmas type character) and Ded Moroz (Grandfather Frost) in Russian (coming from the folk character “Morozko”, “moroz” meaning “frost” in Russian). Because the character was most frequently referred to as “Grandpa Frost” throughout the Soviet Union, I have chosen to use that translation when mentioning him here.

[6] Chokha-akhalukhi refers to the traditional men’s coat and tunic. Nabadi is a big felt cloak worn as an overcoat.