What was the first polyphonic singing like?

Preface

Everything started in 2016, when Rusudan Tsurtsumia, the director of the International Center for Traditional Polyphony at Tbilisi State Conservatoire, presented me with a book by Joseph (Soso) Jordania, Why Do People Sing? Music in Human Evolution, newly translated into Georgian. Jordania’s writings and original ideas have garnered a lot of interest both in Georgia and abroad. Immediately after receiving the gift, I started reading this work.

The book discusses the possible causes of the origin of folk polyphony and paths for its further refinement and development, as well as the conditions and processes that led to the disappearance of many places where polyphony once thrived.

The third chapter was the most interesting for me, as it discussed the characteristic features of ancient polyphonic patterns. Naturally, it is extremely interesting to know how ancient polyphonic songs could have sounded. In this chapter, Jordania proposes seventeen criteria that were characteristic of primordial polyphonic songs. As soon as I read the first item in Jordania’s list, I immediately related it to my personal background and began to apply these criteria to naduri, or work songs, from the Guria-Kobuleti-Imereti region. You could say my subjectivity got the better of me.

Why subjective?

As a practicing performer of folk songs, I have a special interest in qanuri, a certain genre of work songs from the western Georgian regions of Guria, Kobuleti, and Imereti. q’anuri songs from Guria-Kobuleti-Imereti, for a number of reasons. (Naduri is the word for the general genre of collective work songs, while qanuri specifically refers to songs sung during the threshing of corn.) The work songs from these regions are usually sung in four parts (sometimes three, though rarely) and are performed in two choirs.As I continued to read the Jordania’s seventeen criteria for ancient polyphony, each subsequent criterion was even more applicable to the qanuri genre. Later, I wrote to the author himself and asked him whether he thought there were any songs that meet all of these seventeen criteria and which ones, in his opinion, might bring us closest to ancient polyphony. Professor Jordania didn’t hesitate to reply, writing to me that many of the criteria, if not all seventeen, were met by Svan round dances and Pygmy musical folklore. In response, I copied out the list of criteria and added my own commentary on how I thought they applied to the work songs I was interested in. Jordania agreed with my ideas and suggested that I do doctoral research on this topic—which, for some reasons, I declined.

The format of this journal, however, allows me to tell this story and share my thoughts on why I consider the naduri to be an example of ancient polyphony. In what follows, I will share the seventeen characteristics proposed by Jordania, followed by my comments about qanuri songs.

These criteria appear on pages 125–127 of the English-language edition of Why Do People Sing? (2011). In his account, Jordania compiled these characteristic features from different, geographically isolated sites of polyphonic practice, where the probability of preserving ancient patterns andcharacteristics is presumed to be the highest.

Characteristic Features of Primordial Polyphony:

1. The choral singing of our distant ancestors was most likely based on the antiphonal and responsorial alternation of two groups, or of a soloist and a responding group. This is a truly universal feature for both polyphonic and even monophonic cultures, and there is hardly a human musical culture on our planet without any elements of the deep-rooted tradition of responsorial singing.

A folk song like the qanuri, which is antiphonal and performed by two groups or choirs, unambiguously fits this criterion.

2. Choral singing must have included everyone, every layer of a hominid group. This feature is very characteristic for traditional polyphonic cultures, where everyone is expected to participate at some level and there are no formal listeners at all. Strict gender division in singing, or the division of society on performers and listeners seems to be a relatively late phenomenon (unless the situation itself requires the presence of only one gender, like for example, males confronting lions in order to drive them away from a kill).

During the singing of a naduri, every single member of the nadi would be involved in the song. The reason for this is simple: during the nadi, people would sing songs to work with twice as much gusto. The collectivity of the song in this case was due to very practical reasons. In a 1959 interview with the ethnomusicologist Vladimer Akhobadze, Hasan Roqva, one of the oldest naduri performers studied by Akhobadze, said: “If there was no song [i.e., a naduri], a man would not work the land. It was the whip of the field—like a horse needs a whip, that’s what the song was.” Accordingly, to achieve this result, all participants of the nadi had to sing. The luxury of doubling up on the voices was only available for the basses and drones (shemkhmobari).

Kobuleti. Leader - Kamil Takidze. Yvette Grimaud's expedition – 1967

3. The rhythm of choral singing must have been very precise and vigorous. Precise rhythm absolutely dominates in sub-Saharan singing traditions, and in many European and Polynesian polyphonic traditions.

One of the main characteristics of the naduri is a clearly-articulated rhythm, which changes at certain moments. The second or middle voice, known as mtkmeli literally, “speaker”—is responsible for establishing and keeping these precise rhythms.

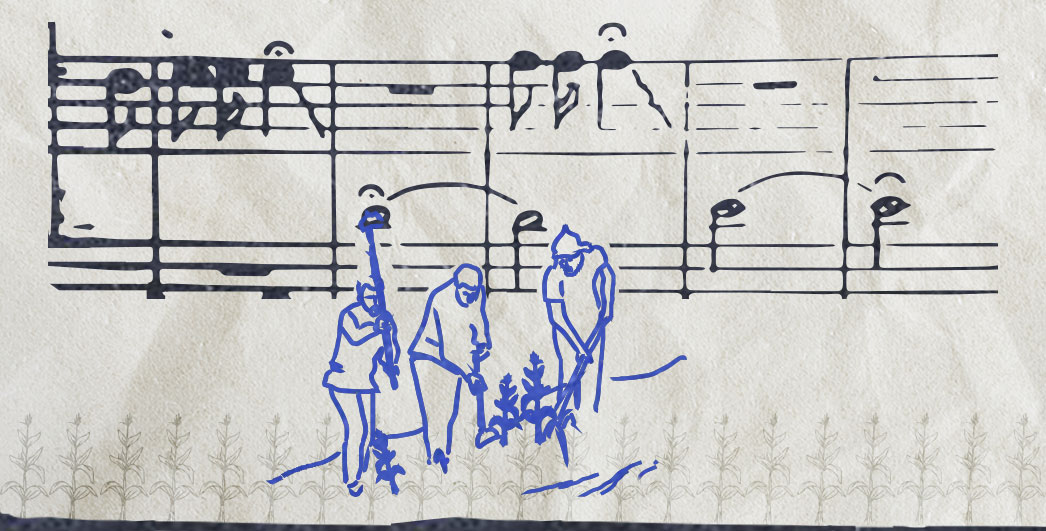

4. The choral singing of our ancestors most certainly was accompanied by a dance, clapping and by bodily rhythmic movements involving all participants. This kind of syncretic unity of singing and dancing is conspicuous in all more or less archaic musical traditions. Even today when we hear rhythmic music, we instinctively want to follow it with tapping, stomping or bodily movements.

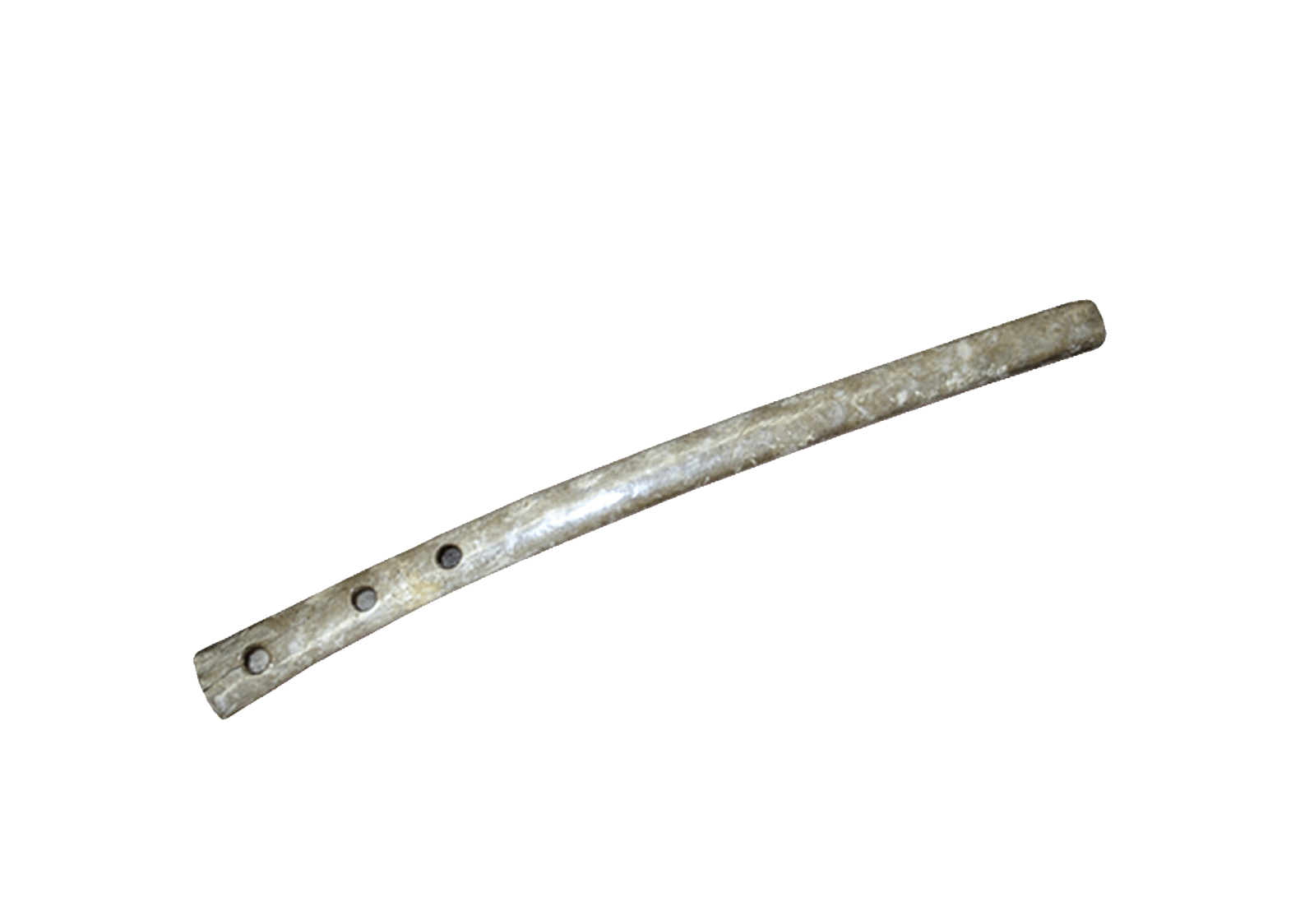

A naduri was not performed standing still: the natural environment for its performance was in the field, working with the soil, which in itself requires body movement. Through the hoe, the body’s movements follow the rhythm of the song. Although it is not dance, it involves rhythmic movement of the body, to which is assigned a specific, practical purpose or function.

5. The use of body percussion is also highly probable for the ancient communal singing of our ancestors. Clapping hands and stomping feet on the ground were probably widespread practices. It is also likely that, for greater effect, stones normally prepared for throwing would be hit against each other. This may be considered the first element of percussion in music.

Avksenti Megrelidze (1877–1953), a renowned performer and researcher of Georgian music, witnessed the performance of naduri in the fields during his lifetime. As he described it, “The pounding of the hoes of 60–70 men was so perfectly, rhythmically aligned with the song that you would think a drum was playing and the song was going along with the drum.” Thus we can recognize this characteristic as fitting the naduri as well.

6. The singing style of our ancestors was most likely loud and straight. Most archaic polyphonic singing traditions are still extremely loud. With every member of the society participating in singing that involves dance and clapping you will hardly ever hear any quiet and gentle choral music.

The naduri is a loud song by its nature; the tradition-bearers who witnessed the naduri songs in situ noted that a naduri would usually be performed very loudly and reach its peak in the final verses.

7. The meter of music was most likely based on duple rhythms (2/4, 4/4). This simplest and most common meter is arguably the most widespread in different cultures of the world (both polyphonic and monophonic), and even in classical music notation it is known as “Common Meter” (expressed by the letter “C” in notation). The related meter 12/8, where each beat is divided into three sub-beats is another good nominee for the earliest human meter. 12/8 is widespread among Central African Pygmies, and is known to many as “swing.”

The beginning of a naduri is usually sung in free rhythm, without meter, though the main part is in 2/4 or 4/4. (Rarely one will encounter a 3/4 meter). But the crucial thing is that the main part of Nadur is built on duple meters like 2/4 and 4/4.

8. The tempo most likely became faster during the performance and the pitch was gradually rising. These features are a usual part of archaic dance-songs. They start at a relatively slow or medium tempo and the tempo gets faster and the pitch rises during the performance in growing excitement. Most music teachers are well aware of the general tendency of music students to play faster and faster as the piece approaches the end.

In general, the increase of tempo (gradually speeding up) and dynamics are universal occurences. Naduri’s pace is likewise variable: it starts slowly and gradually accelerates.

9. In addition to the tempo, it is conceivable that the tonality of the ancient song gradually moved higher and higher. It is well known that raising the pitch increases the emotional power of the music. This is also widely characteristic of traditional performers. I would like to remind the reader of the well-known fact among Georgian ethnomusicologists that Svan and Rach’an singers usually start their slow songs lower, in order to have space to raise the pitch during the song. Even in modern popular songs, raising the tonality has already become a pattern.

The naduri is also variable in terms of tonality: it starts low and tends to rise. The drone part known as shemkhmobari is responsible for not letting the pitch rise too high. We say in Georgian that it tries to “catch” the pitch.

10. Primordial song would have been not only collective, but polyphonic as well. Harmonically, harsh intervals of the second on vowel sounds would also have been prevalent. Dissonant intervals are known to attract the most attention and have the greatest audio effect on the listener. (I already mentioned that car horns often have dissonant intervals; they attract the attention of forgetful or confused passerby more quickly.)

This criterion is clearly visible in naduri songs, where intervals of the second are often present.

11. The drone is the best nominee for the claim of primordial universality. Drone is not popular in sub-Saharan Africa, although there are certain African cultures where drone is strongly present (e.g., among Maasai in East Africa, or Kpelle in West Africa, and even Pygmies). Also, drone polyphony with secondal dissonances (D/D style), is scattered so widely in spectacularly geographically isolated regions of the world that we already discussed the possibility of D/D polyphony being one of the oldest types of group singing among humans. [Note: Jordania’s book proposes a style of polyphony known as Drone/Dissonant or D/D.]

In the naduri, the drone is found in the form of the shemkhmobari, which in the song holds one note in a fixed, motionless manner, although there are naduri songs where the shemkhmobari moves. Note that, unlike other drones, for instance in Kakhetian music, the shemkhmobari drone is considered a “high” voice from the point of view of the tonal distribution of the voices: in pitch it is close to the second and first voices.

"Kumuris Naduri" – Kumur-Dutskhuni’s choir. Leader – Givi Chapodze, Edisher Garakanidze's expedition, director – Dimitri Gugunava. 1988.

12. Ostinato is possibly the most universal type of vocal polyphony. There are hardly any polyphonic traditions that do not employ the ostinato principle (based on multiple repetition of the same short phrase) to some extent. Drone and ostinato principles are not mutually exclusive, on the contrary, they often coexist.

Moments of ostinato polyphony are often found in naduri songs, especially in the concluding verses.

13. I have to suggest that there was no separate function of a bass in the ancient primordial polyphony of our ancestors. Sub-Saharan African polyphonic singing does not seem to be using a bass as a functionally separate part. Even African ostinatos are not necessarily in a lower register, and the drone in traditional music is often in the middle of the polyphonic texture. This is also the case in ancient Bulgarian, Latvian, Tibetan, Vietnamese, Nuristani polyphonic songs. The placing of the bass in the middle of the texture is found in Georgian naduri songs from the Guria-Ach’ara regions, in particular in the initial, three-voice section of the song, where the continuous drone-bass (shemkhmobari) is in the middle of the texture.

Here Jordania himself mentions the function of the bass in the naduri songs from Guria and Ach’ara, although it should not be forgotten that “bassless,”—i.e., three-part naduri songs—can be found in the highlands of Guria, as in the regions of Surebi, Van-Zomleti, and Qumuri. (This last region is technically in Imereti, although the naduri from there is essentially identical to the one from Surebi.)

14. The yodel also has a claim for inclusion among the characteristics of ancient polyphony. It is by no means distributed in a lot of cultures, but nevertheless different forms of yodel are present in isolated pockets of European, sub-African and Pacific polyphonic cultures.

Yodeling, known as k’rimanch’uli or gamqivani in Georgian, is a vocal technique present in all naduri songs, so this criterion is uniquely fitting.

15. Verbal text must have been absent or kept to a bare minimum in this primordial polyphony (as it is in the polyphony of the Pygmies). Interjections and nonsense syllables must have been prevalent at this stage. Besides, we are talking about such an archaic period of time when the presence of articulated speech was very unlikely. Repetitive, mantra-like verbal formulas are the most likely candidates for the earliest “song lyrics.” Repetitive and rhythmic mantra’s ability to put humans into an altered state of mind is well known.

In naduri songs, the significance of the text is kept to a minimum. In fact, text is used only at the beginning, and in most cases only by the mtkmeli, the middle voice. Naduri are generally built on syllables that have lost their semantic meaning.

16. There is a good chance that the scale basis for the most ancient form of primordial polyphony was an anhemitonic pentatonic, without half-tones.

The semitone was not and could not be a characteristic of the naduri. All existing theories related to the tuning system of Georgian folk song say the same thing. According to these theories, there is a great tendency towards whole tone in the tuning of Georgian music.

17. The performance was naturally leading participants to the state of trance. To transform individual members of the group into fanatically dedicated members of a unit—this was actually the core function of the whole action.

The final stanza of the naduri is essentially a trance, as all voices actually make the same sounds when singing, the tonality is at its peak, and it is at this point that the individuality is lost and the group of singers becomes one.

Jordania concludes his discussion of these characteristic features with a summary:

To summarize, we have the following description of the ancient ‘primordial’,

or ‘proto-polyphony’:

This was loud, responsorial singing of a large mixed group, rhythmically very precisely organized (most likely in a duple rhythm), accompanied by rhythmic movements, stomping, body percussions, and stone hitting. The choral sound was polyphonic, based on sharp dissonances, the tempo rose during the singing/dancing, as well as the pitch, together with the general dynamics. Polyphony was based on ostinato and drone principles, there was little or no text (mostly interjections or mantra-like repeated verbal formulas), and the function of a bass part was not yet separated. Participants of this primordial session were going into the state of battle trance, where feelings of fear and pain would disappear. Putting participants into this altered state of consciousness was the central function of the primordial singing and dancing sessions. (127–128)

To illustrate how exactly the image described above suits the form of performance and, partly, the content of “Naduri", here is a naduri from Kobuleti, “Jikura—Tetri Kori,” performed by Ensemble Adilei:

Thus, my comments on the above criteria point to the archaic nature of Naduri's song. At the same time, at first glance, Naduri's song by its monumentality and complex structure makes one think that such a developed musical structure must be the result of time-honoured vocal thinking. However, if you look closely, each voice of Naduri is not characterised by a sophisticated melodic line, and its complex four-part structure is created by combining these 'simple' melodies of the individual voices.

[1] Jordania, Joseph. (2016). Genesis of Vocal Polyphony in the Light of Human Evolution.Logos, 2016 (In Georgian), pp. 236-241.

[2]The word nadi refers to a common form of mutual assistance during periods of harvest work, when groups of men would band together to harvest a particular area. A naduri would have been sung during the nadi to motivate and consolidate the energy of the workers. See more on the topic of nadi here.

[3] Avksenti Megrelidze, Guruli naduri (Gurian naduri), edited by Ilia Tavberidze (Tbilisi: Guriis sulieri da kult’uruli paseulobis shests’avlisa da p’op’ularizatsiis tsent’ri, 2006), 13–14.

%20%E1%83%A1%E1%83%90%E1%83%9C%E1%83%93%E1%83%A0%E1%83%9D%20%E1%83%9C%E1%83%90%E1%83%97%E1%83%90%E1%83%AB%E1%83%94%20-%20%E1%83%9E%E1%83%A0%E1%83%9D%E1%83%94%E1%83%A5%E1%83%A2%E1%83%98%E1%83%A1%20%E1%83%AE%E1%83%94%E1%83%9A%E1%83%9B%E1%83%AB%E1%83%A6%E1%83%95%E1%83%90%E1%83%9C%E1%83%94%E1%83%9A%E1%83%98%2C%20%E1%83%A1%E1%83%90%E1%83%A0%E1%83%94%E1%83%93%E1%83%90%E1%83%A5%E1%83%AA%E1%83%98%E1%83%9D%20%E1%83%A1%E1%83%90%E1%83%91%E1%83%AD%E1%83%9D%E1%83%A1%20%E1%83%AC%E1%83%94%E1%83%95%E1%83%A0%E1%83%98-min.jpg)

.jpg)