The Institution of the Divinely Chosen Preacher in Georgian Folk Tradition

In widespread folk beliefs, a preacher is someone believed to be in direct contact with a deity — a person who communicates the deity’s will to the people, speaks on its behalf, and thus serves as an intermediary between the divine and humanity. Tinatin Ochiauri, in her work From the History of Ancient Georgian Beliefs, notes that in ancient Georgian literary works, the term “preacher” appears with a somewhat different meaning: here, the preacher is not only a messenger of the deity’s will and desires but also, more generally, a messenger on behalf of another — a transmitter or herald of any news.[1] Thus, in literary sources, the term carries a broader, more secular sense, referring to someone who conveys a story or speaks for another, whereas in folk tradition, the preacher’s role is specifically to transmit divine truth. In both cases, the common thread is that the preacher speaks on behalf of someone else. In the case of a shrine preacher, the term refers to a figure who, in folk conceptions, proclaims to the people the demands and desires of a saint or deity.

The folklore concept of a preacher is first mentioned by Vakhushti Bagrationi.[2] He refers to the preacher from Pshavi and emphasises the significance of the preacher’s word among the people. After this mention, references to preaching in literature are practically nonexistent until the 19th century and the second half of the 20th century. Discussions of preaching in sources from this later period (from the second half of the 20th century onward) mainly focus on the mountainous regions of Eastern Georgia – Tusheti, Pshavi, Khevsureti, Khevi, and Mtiuleti.

According to popular belief, becoming a preacher was never dependent on a person’s own will. A special folk concept, damizezeba (“being marked by a deity”), referred to the process by which the deity chose the individual; this calling manifested in the form of a nervous disorder. Outside the mountainous regions of Eastern Georgia, relatively little is known about such “marked” preachers in the lowland regions of Kartli and Kakheti, and as for Western Georgia, according to Ochiauri, nearly nothing is recorded.[3] It cannot be asserted with certainty that the institution of preaching was characteristic solely of Eastern Georgia, but one can certainly conclude that in this part of the country the tradition was relatively more developed and preserved for a certain period.

Two Types of Marked Preaching — Selection and Punishment

In the mountainous regions of Eastern Georgia, specifically in Khevsureti, Ochiauri presents two scenarios for marked preaching:

- Selection Based on Various Qualities (for example, piety, fear of the deity, or having a preacher among one’s ancestors). A person chosen in this way would manifest their calling through physical and emotional symptoms: headaches, heart pains, crying, fainting, lack of appetite, or apathy. Since the individual had committed no wrongdoing, the illness was explained as caused by the shrine, and it was said that the shrine “lays its hand upon her.”[4]

- Punishment — the deity could also afflict a person for punishment in cases where “an individual offended the Son of the deity through some action, such as failing to provide sufficient offerings or service to the deity, trespassing in a sacred place, or using the shrine’s land or forest, among other things.”[5] In such cases, the illness manifested as a temporary, non-nervous disorder (for example, pain in the head, eyes, or sides, lung disease, and other ailments).

According to Ochiauri, a similar pattern is observed in Pshavi as well as in Khevsureti and Mtiuleti — the shrine selects the future preacher and marks them. In the lowland regions of Eastern Georgia (Kartli and Kakheti), however, becoming a preacher takes on a different character: while in the mountains the marking occurs due to the deity’s favour, in the lowlands it is caused by wrongdoing committed by the individual. In both Kartli and Kakheti, a person is marked because of a specific offence against a shrine, and the marking serves as a form of punishment.[6] In such cases, the marking is always preceded by the shrine taking a person as its mona (literally “slave” of the shrine, understood in the lowlands as a ritual devotee). Importantly, a person marked as a punishment in the lowlands exhibits the same symptoms as one marked by divine favour in the mountains.[7]

The Shrine’s Slave in Kakheti

Nino Abakelia describes a general picture of the shrine’s slave in her article “The Institution of the Shrine’s Slave in Kakheti” as follows:

According to field ethnographic materials, a slave of a shrine is a person marked by the shrine for some offence (mostly women, although men could also be chosen). The shrine itself selects its slave to serve it and endows them with intellect, wisdom, and divine talent so that they may convince others of God.[8]

As already noted, neither preaching for the shrine nor being the shrine’s slave are matters of personal choice. According to Abakelia, the chosen individual initially resists the shrine, suffering pains, heart palpitations, fainting, and other symptoms. When they fall into the state of preaching, they learn — through dreams or hallucinations — whose sanctuary they serve as a slave of, and become a mediator between people and the deity. The connection with God is established as follows: a person in distress approaches the slave and tells their story. The slave then “reports” it to Saint George (or another saint, depending on which sanctuary the slave serves); Saint George (in corporeal form) reports it to the chief angel (the force of the incorporeal), and the chief angel communicates it to God. Through the slave, people learn the appropriate reasons for how they should act to gain the favour of the shrine.[9]

In addition to serving as mediators, the shrine’s slaves were also required to fulfil other obligations before the shrine. For example, some of those marked would “pledge to spend nights in vigil at the shrine, dedicate a sacrificial animal, light candles, abstain from foods forbidden by a fortune-teller,[10] wear special clothing, and so on. If the shrine’s heart softened, it would lift the punishment, and the marked person would recover.”[11]

Comparison of the Terms Damizezebuli (Marked) and Dach’erili (Possessed)

It is important to distinguish between the terms damizezebuli (“marked”) and dach’erili (“possessed”). According to Ochiauri, in Khevsureti it is difficult to determine the precise difference in meaning between marked and possessed — and the same applies to the lowland region. However, a conventional distinction can be made as follows: “A person may be considered ‘marked’ if the shrine releases them after fulfilling certain obligations, while one who is ‘possessed’ is someone who cannot escape becoming the shrine’s servant.”[12] Thus, if a person is possessed, regardless of fulfilling everything the shrine demands of them, they cannot free themselves from slavery. As I have already mentioned, the stages of possessed and marked come before the state of becoming a shrine’s slave — a topic to which I will return, with examples, when discussing Vera Bardavelidze’s work Among the Ivris Pshavelebi [Pshavs of the Iori Valley].

It is interesting to consider the roots that, in popular beliefs, link marked and possessed to supernatural forces. Nunu Mindadze addresses this issue in her book Kartveli Khalkhis Sameditsino Kultura [Traditional Medical Culture of the Georgian People], noting that when the real cause of an illness is not apparent, people explain it through a supernatural cause.[13] This gives rise to magical-religious medicine — a healing practice based on supernatural understanding and encompassing a system of beliefs and notions regarding the causes of diseases.[14] Mindadze defines the term marked as follows:

Folk etiology also associated certain illnesses with benevolent forces. The people of Georgia believed that the world’s benevolent powers — God, angels, deities, saints — while caring for human well-being, also fulfilled the role of judge over humans. The judgment they imposed most often took the form of illness. Benevolent forces could also afflict a person to bring them into their service. In both cases, the act of punishing a person through illness was referred to in some regions of Georgia as damizezeba.[15]

Such divine punishment or choosing could manifest as a mental illness. Mindadze also offers an interesting explanation of the shrine’s slavery: in some regions of Georgia, the term damonebuli (“enslaved”) is used to describe a person who has lost their abilities — becoming inactive, sometimes even losing the ability to speak. Accordingly, being enslaved by a shrine meant that the shrine punished a person for an offence, depriving them of the ability to live normally. Thus, a person destined to become a shrine’s slave was struck by a serious illness. In exchange for healing, they were dedicated as a slave of the shrine, either for a limited period[16] or for life.[17]

Mindadze compares falling into the state of preaching with a person being possessed by the devil. Although the processes are similar in form — both involve visions, delusions, and inner resistance — the symptoms of the disorder allowed for different interpretations. In folk understanding, when a person entered a trance, prophesied, and “spoke forth” (ენას გამოიტანდა), this was seen as a divine phenomenon and indicated falling into the state of preaching.[18] In contrast, if the person behaved aggressively, they could be restrained, and this was considered a diabolical affliction. Thus, different symptoms of the same mental process formed the basis for distinct religious-mythological interpretations: trance signified divine selection, while aggression served as evidence of possession by the devil.[19]

Marking and Heredity

The role of heredity in marking and possession is also noteworthy, as it is observed both in the mountains and in the lowlands. This factor, in turn, is associated with nervous disorders, which in some cases are hereditary. On this topic, Ochiauri draws a parallel with shamanism, which was likewise considered a hereditary ability, and generally describes the phenomenon (we also encounter this analogue in Khevsureti and Kakheti):

To become a shaman, a person must have a particular morbid constitution, extreme excitability, a tendency toward ecstatic convulsions, various kinds of hallucinations, and other traits. In short, they must be possessed by a certain intensity of hysteria. Hysteria, as is well known, is easily transmitted hereditarily.[20]

Khevsur preachers who were marked or possessed were often from the same family line, since they already had a preacher among their maternal or paternal ancestors. It was not strictly necessary for a preacher to have another preacher among their forebears; however, because preaching involves communicating the deity’s will to the people and this “ability” manifests through symptoms of nervous disorder, the hereditary transmission of neurotic or psychological tendencies provides a plausible explanation for why preachers were often connected by lineage.

In the case of shamanism, the reason is somewhat clearer: it is certain that among the ancestors on either the maternal or paternal line there was a shaman. Moreover, performing the role of a shaman requires neurotic or psychological tendencies, which are naturally hereditary.

Returning to marked preachers, the process of becoming a preacher — whether through divine selection or by being taken as a slave of the deity for punishment — is accompanied by a particular psychophysiological state, which in many cases can be explained by hereditary neurological or psychological predispositions.

Thus, heredity did not constitute a necessary condition for being chosen as a preacher; it was only one of several factors, which could be combined with others. Nor can it be said that every descendant of a preacher inevitably became a preacher. Rather, the hereditary background created psychophysiological and social conditions conducive to the choice of a preacher: on the one hand, the transmission of neuropsychological traits from ancestors created a predisposition, and on the other hand, social expectations and tradition transformed this predisposition into an actual religious status — perceived as a sign from the deity and a proof of being chosen.

The Ritual of Preaching in the Lowlands of Eastern Georgia

Since in the lowlands of Eastern Georgia divine favour is excluded and marking occurs as a form of punishment for wrongdoing, the ritual of preaching also takes on a different form. Comparing the marked individuals of Khevsureti and the lowlands, Ochiauri notes that in the lowlands, ritual dance and chanting take place before the shrine — something not characteristic of the Khevsurs. It is possible that the Khevsurs also entered the state of preaching during feast days, yet their preaching followed a traditional pattern: it was not preceded by dance-induced ecstasy, falling to the ground, and then preaching. A Khevsur who fell into the state of possession would either stand or sit while preaching (“speaking forth”). In the lowlands, by contrast, we find the opposite picture.[21]

The Feast of Lashari Cross

Unique material concerning the participation of marked or possessed individuals from the lowlands, as well as female shrine slaves, in the ritual of the feast day (dgheoba), is presented by Vera Bardavelidze in her work Among the Pshavs of the Iori Valley. Bardavelidze personally witnessed the celebration of the Feast of Lashari Cross in the Alley of Khathkhvevi, a place that takes Kakhetian pilgrims four days and nights to reach. During the feast, they spend the nights beside the Lashari Cross and camp in the valley. The general scene is described as follows:

We passed through the alley and headed toward the Lashari Cross. It is situated on a wide mountain plateau, encircled by a thin belt of forest. The western side of the plateau is occupied by the Kakhetians’ carts, covered with awnings. The wheels of the carts, unyoked from the oxen, rest on the ground, and beneath the overturned carts, in the shade, the women bustle about. Nearby they have arranged hearths and are preparing food. The carts belong to believers from Kvareli, Matani, Eniseli, and Shilda. Among the gathered crowd are also many non-believers. It is Saturday. Almost no Pshavs are to be seen in Lashari…

Most of the Kakhetian pilgrims in Khatkhvevi are barefoot and have their heads covered with white scarves made of calico or gauze. Some of the men, instead of white scarves, wear red ones. In addition, almost every man has strips of white calico tied around his waist, either in place of a belt or together with it. Young women and children have red or pink ribbons thrown over their shoulders, crossing diagonally over the chest and back and tied at the hip. Some middle-aged and elderly women have a triangular piece of red cloth sewn onto the front of their dresses, while others have a square-shaped red or white patch, or an ornament made of strips of the same colours braided into a lattice pattern, adorning their chests. The fortune-teller is dressed entirely in white garments made of calico. The “possessed of the shrine” wear only white upper garments of calico. Among them, one stands out — Dariko A-shvili — who, in addition to a white upper garment, wears a red skirt painted with leaf-shaped yellow patterns, dedicated to the shrine.[22]

According to Bardavelidze’s diary, the feast of the Lashari Cross is celebrated in this kind of environment, accompanied by dance and singing, often with the accompaniment of the panduri.[23]

b) The Marked Individuals at the Feast of Lashari

Based on Bardavelidze’s notes, an intriguing spectacle begins once the possessed Dariko breaks through the circle of dancers, throws herself to the ground, and adds shouting to her movements, starting to roll over. Through this rolling, she approaches the northern edge of the shrine’s enclosure, while the gathered crowd lays shawls on their knees. Dariko begins to rock her head from side to side and to shout: “Hey, hey, tormented, tormented child, child,” and so on. She preaches. It seems as if the shrines (Georgian khati, ხატი)[24] themselves speak of her sins and threaten her through her own mouth. “What did you think, that I would spare you for destroying the pillar of the truth, for bringing bones into my domain, for closing Nekresi?[25]… hey, hey, tormented one!” she shouts, trembling as she speaks.[26]

In parallel with this scene, playing on the panduri begins, which, according to local belief, is meant to delight the angels and, as a result, help the fallen stand up and continue dancing. Dariko’s shouting reveals another important factor that distinguishes the marked individuals of the mountains from those of the lowlands. In the mountains, preaching usually addresses communal topics — such as expected harvests and weather, the likelihood of enemy invasion, or the anticipated mortality or illness in the village — and elements of ritual or ecstatic behaviour are less pronounced. In the lowlands, by contrast, the content of preaching is primarily concerned with the redemption of personal wrongdoing, confession of sins, and the reinforcement of belief in the icons.

In her description of this scene, Bardavelidze provides the text of a hymn that was traditionally sung during the act of falling into the state of preaching:[27]

Nana da Nana, Nana da Nana![28]

O victorious Lashari of ours,

Iav Naninao!

May the violet and the rose bloom and flourish,

May the blossomed violet and the rose protect Lashari.

I tell you, Iav Nana,

Hail to your power,

May you guide us at the forefront.

May your power prevail; look down upon us —

Your suffering little ones are here.

We beseech you, we implore you, Iav Naninao,

Look down upon us; your little flock is sorrowful,

They are hungry, Iav Naninao.

Nana da Nana, I tell Nana,

Our Mother, God-bearer,

Iav Naninao.

Mother, Mother God-bearer,

You are the protector of the suffering,

May the rose bloom over the little ones.

Nana da Nana, hail Queen Tamar!

Let us remember her with Iav Nana,

Iav Naninao.

Hail our Queen Tamar, who leads at the forefront,

Sweetly and delightfully, may she be blessed by the blossomed violet and rose,

Iav Naninao.

Look down upon the suffering; protect them,

They are little and sorrowful,

Iav Naninao.

Nana da Nana, Nana da Nana!

O victorious Nekresi, master of Gavazi,

Nana da Nana, Iav Nana!

Hail the source,

Who rules over the Pshavs, Iav Naninao.

Nana da Nana, Nana da Nana!

O Alaverdi, fighter and victorious,

Iav Naninao.

Nana da Nana, our Mother Barbara,

Protector of the land, guardian of all,

Protector of all the sorrowful, Iav Naninao.

Hail, hail Mother Barbara,

Look down upon the very sorrowful,

They are little ones, Iav Naninao.

It is enough to invoke you with Iav Nana,

It is enough for the little ones to rejoice

Among their peers, Iav Naninao.

Nana da Nana, Nana da Nana!

O our fallen and shattered pillar of the true God,

We approach you with Iav Nana, Iav Naninao.

Nana da Nana, Nana da Nana!

Look down upon the suffering; they are suffering,

Little youths, Iav Naninao.

Nana da Nana, Nana da Nana!

Hail to the three hundred and sixty-three holy Georges,

Iav Naninao.

Hail those who send the violet and rose for the journey of the suffering,

May the suffering be freed from the yoke,

Iav Naninao.

Hail, may they be freed,

May the yoke from the suffering be removed,

Iav Nana, Iav Naninao.[29]

Despite the singing (chanting), Dariko remains motionless on the ground, until another marked individual — Eliko from Shilda — also falls. Eliko is given a panduri, and while playing it, both women join the people in dancing.

Bardavelidze spoke with Dariko personally, who explained the story of her being marked as follows:

A few years earlier, she, along with other young people, was assigned to collect the waste and debris in the village. They decided to dispose of it in the abandoned and partially ruined church dedicated to the “Pillar of Truth,” which stood in Shilda. “We brought the gathered debris to the churchyard, but none of us dared to place it inside the church first,” Dariko recounts. “At that moment, I decided to set an example for the others. I entered the church, aimed the bones at the icon, and threw them.”

A week later, Dariko had a troubling dream, soon lost her appetite, became thin, and eventually experienced what has often happened to her since — what occurred today in front of our eyes. “I never believed that anything would happen to the shrine,” Dariko continues, “until I started throwing the bones into the ‘Pillar of Truth’ church, participating with great zeal in the destruction of the building and the closing of Nekresi Church.” She then added hesitantly: “Even now, I don’t believe in the shrine; it’s not my fault that this is happening to me.”[30]

Dariko was marked for precisely this reason. After she recounted her story, Eliko again fell to the ground, began preaching, hit her head against the stones, and crawled toward the water. Eventually, the crowd helped Eliko to stand. They then played the panduri; Eliko resumed dancing, and the feast continued. As we can see, the state of ecstasy is neutralised once again through dance and music, in which the marked individual also participates.[31]

c) The Female Slave — Mediator between the Shrine and People

Another significant episode from Bardavelidze’s diary of the Feast of the Lashari shrine concerns the female slave of the shrine. According to the diary, another girl, named Margo, fell to the ground. A panduri was immediately placed on her chest. She grabbed the instrument and tried to tune it, though she disliked its sound, grimacing as she did so. Eventually, Margo threw the panduri aside and placed her hands on the ground. At that moment, a woman, who was the shrine’s slave, shouted “Bring me the panduri; I will make her jump out of the land immediately.”

Bardavelidze describes the appearance of the shrine’s slave as follows: “The woman wears a black dress with white dots, with a white calico ‘lattice ornament’ hanging on her chest, and covers her head with a black scarf; she is about 65 years old, stocky, dark-haired, and of medium height.” At one moment, her headscarf slipped, revealing that her hair had been shaved. The gathered crowd explained this as follows: the shrine has such powerful angels that they do not allow the hair to grow; if it did, it would be set on fire and burned.[32]

The shrine’s female slave began playing the panduri, yet Margo remained motionless. Finally, the slave said, “She has fallen into preaching.” Once Margo opened her eyes and was helped to stand, the shrine’s slave, who had initially taken it upon herself to bring Margo to consciousness, began preaching. Her preaching was an improvised, verse-like performance, accompanied by the panduri. After finishing, the slave threw down the panduri, began spinning and shouting, and then rolled toward the shrine’s enclosure. The crowd stopped her, after which panduri playing resumed, and as usual, the accompanying dance of the feast continued.[33]

The episode concluded with the female slave approaching the shrine’s enclosure together with Dariko. She led the sacrificial calf herself and, after murmuring and guiding it around the temple, directed the feast participants to the spot where the calf should be slaughtered. This marked the beginning of the process of sacrificing the calves: each participant led their calf to be killed at the place indicated by the female slave.

Bardavelidze’s description of the Feast of the Lashari shrine shows, on the one hand, the ecstatic state of the possessed and marked individuals, and on the other, the role of dance, singing, panduri playing, and preaching. It seems that the female slave of the shrine holds a particularly important role, exerting decisive influence both during the episodes of possession and in the moments of calf sacrifice.

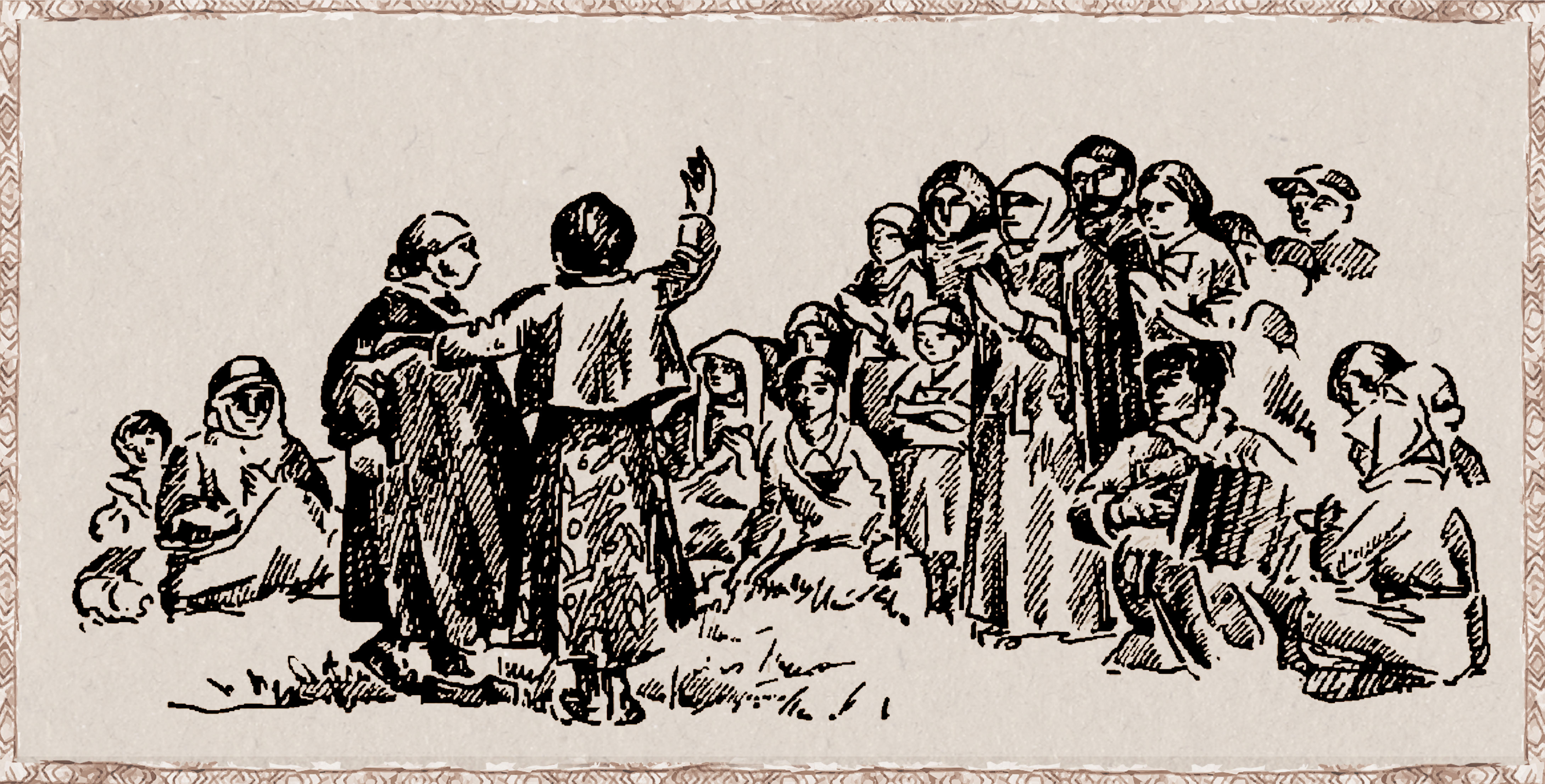

.-%E1%83%93%E1%83%A6%E1%83%94%E1%83%9D%E1%83%91%E1%83%90%E1%83%96%E1%83%94-%E1%83%AE%E1%83%90%E1%83%A2%E1%83%A8%E1%83%98-%E1%83%90%E1%83%A1%E1%83%A3%E1%83%9A%E1%83%98-%E1%83%91%E1%83%90%E1%83%A0%E1%83%A8%E1%83%98-%E1%83%9B%E1%83%AA%E1%83%AE%E1%83%9D%E1%83%95%E1%83%A0%E1%83%94%E1%83%91%E1%83%98-%E1%83%A5%E1%83%90%E1%83%93%E1%83%90%E1%83%92%E1%83%98-%E1%83%A5%E1%83%90%E1%83%9A%E1%83%94%E1%83%91%E1%83%98.jpg)

Lowland Lay Women Preachers (kadagis) at the Shrine of Kmodisgori (Pshavi) during the Feast Day

Conclusion

Based on the sources and information discussed, we can conclude that, while preaching at the shrine in the mountains of Eastern Georgia and serving as a shrine’s female slave in the lowlands share certain similarities, they also had different functions and social expressions. In the mountains — specifically in Khevsureti — the preacher of the shrine is chosen by the deity and is therefore marked, whereas the female slave of the shrine suffers punishment for wrongdoing and is possessed by the shrine. In each case, the shrine’s choosing manifests in nervous disorders, which are interpreted in light of the individual’s psychological state and its folk interpretations.

In the lowlands, a marked individual may become a preacher of the shrine (the shrine’s slave). If she is only marked, she may still escape slavery; if possessed, she cannot free herself, and once she ceases resistance, she becomes the shrine’s slave.

The preacher in the lowlands confesses her sins and seeks liberation, and the favour of the shrine, which is reflected in the forms of expression: in the mountains, ritual elements are minimal or entirely absent during preaching. In the lowlands, however, preachers often “fall,” entering a state of ecstasy while preaching, accompanied by elements characteristic of the feast — playing the panduri, dancing, singing, chanting, and so on.

Nino Brailashvili — illustrations for Vera Bardavelidze’s Diary

[1] Ochiauri, Tinatin. 1954. Kartvelta Udzvelesi Sarumsoebis Istoriidan [From the History of Ancient Georgian Beliefs]. Tbilisi: Academy of Sciences, p. 4.

[2] Bagrationi, Vakhushti. 1941. Ats’q’era Samefosa Sakartvelosa [Description of the Kingdom of Georgia]. Tbilisi: Tbilisi State University Press, pp. 86–92.

[3] Ibid., p. 24.

[4] Ibid., p.16.

[5] Ibid., p.16. “Son of deity” is used here in its pagan, pre-Christian sense and does not refer to Christ; after the coming of Christianity, the concept developed into a syncretic form.

[6] Ibid., p. 29.

[7] Ibid., p. 30.

[8] Abakelia, Nino. 1982. “Khatis Monobis Instituti Kakhetshi” [The Institution of the Shrine’s Slave in Kakheti]. Issues of the History of Georgia, pp. 121–128. Tbilisi: Metsniereba, p. 126

[9] Ibid., p. 126.

[10] In Khevsureti, a preacher could perform their service both at the shrine and at home. Preaching at the jvari (literally “cross,” referring to the local shrine) usually took place in connection with matters of communal importance — such as appointing the shrine’s servants, consolidating the shrine’s property status, or consulting the preacher in resolving issues of social significance, and so on.

Preaching at home, on the other hand, was connected to personal and family matters. For instance, a preacher set up at home would be approached in cases of illness, loss of livestock, poor harvest, or other misfortunes. It was this domestic form of preaching that came to assume the function of divination — the preacher would foretell for the person who came to them, addressing matters of personal concern.

A similar situation is observed with the preachers-diviners (kadag-mkitkhavi) in the lowlands, since people also come to their homes for divination. However, the process itself differs: during preaching, the person enters a state of ecstasy (shouting, crying, and so on), while during divination they gaze at a specific object (a bowl of water with candles, charcoal, a knife, etc.) and speak.

[11] Ochiauri, Tinatin. 1954. Kartvelta Udzvelesi Sarumsoebis Istoriidan [From the History of Ancient Georgian Beliefs]. Tbilisi: Academy of Sciences, p. 32.

[12] Ibid., p. 33

[13] Mindadze, Nino. 2013. Kartveli Khalkhis Traditsiuli Samedicino Kultura [Traditional Medical Culture of the Georgian People]. Tbilisi: [s.n.], p. 117. Available at: https://www.iverieli.nplg.gov.ge/bitstream/1234/297892/5/QartveliXalxisTradiciuliSamedicinoKultura_2013_Gateqstebuli.pdf

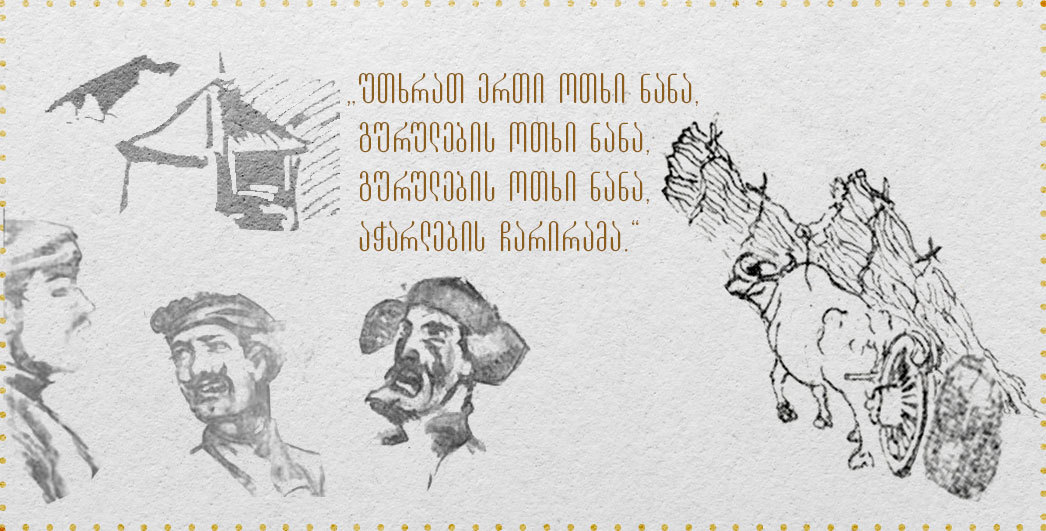

[14]A good example of this is the illness caused by the so-called batonebi [lords] according to folk beliefs. The batonebi are evil spirits that cause diseases such as measles batonebi, smallpox batonebi, whooping cough, and others. In folk understanding, these spirits take up residence in a person’s (often a child’s) body and make them ill. The batonebi have their own rules, which they impose on people. If the patient’s family disregards these rules, the batonebi become angry and “take” the patient with them — that is, they kill them. The nana of the batonebi (a healing song) is part of these rules, and this song is sung precisely to appease the batonebi. [For articles dedicated to the batonebi, see other issues of our magazine: https://geofolk.ge/en/article/qartvelta-codna-infeqciur-daavadeba-batonebze-da-mati-gamovlineba-folklorshi/304/ and https://geofolk.ge/en/article/batonebis-nanina--tsyalobismieri-epoqis-kvali-qartul-simgherashi/79/.]

[15] Mindadze, 2013, p. 146.

[16] A reader might associate this with the Christian institution of the salos (holy fool), but the two phenomena are fundamentally different. A salos chooses the path of the “fool for God” for the perfection of the soul, while remaining mentally healthy. In contrast, a shrine’s slave usually experiences a genuine nervous disorder, yet in folk understanding this condition is perceived as a “consecration” by the shrine and constitutes the prerequisite for assuming the role of mediator between deity and the people.

[17] Ibid., p. 152.

[18] Ibid., p. 24.

[19] Ibid., p. 154.

[20] Ibid., p. 26.

[21] Ibid., p. 35.

[22] Bardavelidze, Vera. 2003. Ivris Pshavlebshi [Among the Pshavs of the Iori Valley]. Tbilisi: Kvirioni, 41.

[23] A traditional Georgian three-stringed plucked or strummed instrument, common in all regions of Eastern Georgia.

[24] Khati (ხატი, literally “image,” “icon,” or “picture”): in the mountainous regions of Georgia, a traditional sacred object or site associated with a local deity; not an “icon” in the Christian sense, but a pre-Christian cult image or the dwelling place of a pagan divinity.

[25] A historic and archaeological site in eastern Georgian region of Kakheti.

[26] Ibid., p. 42.

[27] Ibid., pp. 43-45.

[28] Vocables that serve as ritual exclamations or invocations.

[29] Another variant of this song can be seen here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xCInypNpnbo. This version, “Ghvtis Karze Satkmeli Iavnana” [Iavnana to be spoken at God’s door], calls into question the view that singing at God’s door in the lowlands is solely associated with the atonement of personal wrongdoings and sins.

[30] Ibid., p. 46.

[31] The text does not indicate when Eliko was marked, but she arrives at the feast already in this state and, accordingly, falls into it. In other words, both Dariko and Eliko “reveal” their marked state at the feast and begin preaching.

[32] Ibid., p. 48.

[33] Ibid., pp. 48-51.