The Father of Georgian Choreography and a Wizard of Sport

David Javrishvili — one of the founders of Georgian artistic gymnastics, a choreographer, People’s Artist of Georgia, and an outstanding researcher of national choreography — made a significant contribution to the development of Georgian folk and classical choreography.

Javrishvili did not grow up in an artistic family, and had never dreamed of becoming a dancer or choreographer. He began his career in artistic gymnastics and later brought about a true revolution in the history of Georgian folk dance.

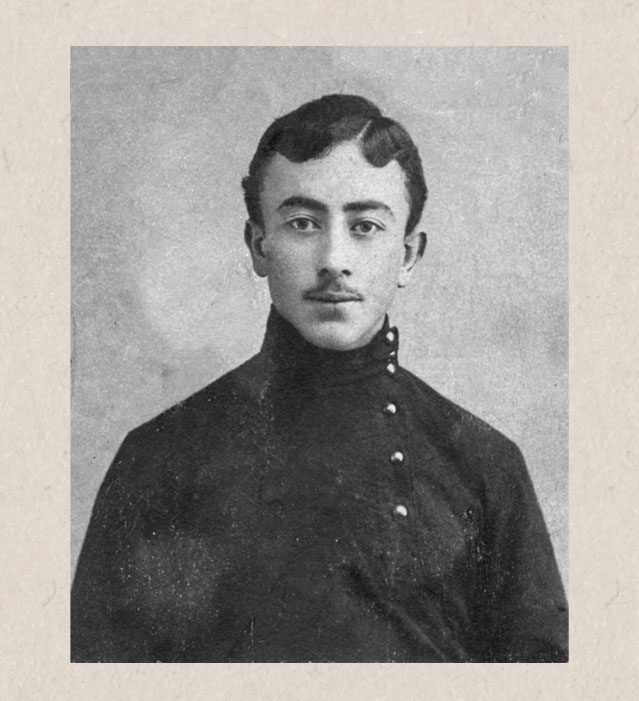

He was born in 1894 in the village of Ertatsminda, in the Gori uyezd (Gori district). He graduated from the Georgian Gymnasium in Tbilisi in 1914, then attended a military academy and, as a young cadet, went to the Turkish front. Three years later, in 1917, he became one of the founders and leaders of the Amirani sports society. His biographer and student, Lili Gvaramadze, notes that “a constant striving for movement, liberation from passivity, and the expression of creative initiative were the distinguishing traits of David Javrishvili.”[1]

David quickly had to choose between a military career and sports. He became one of the founders of the physical education movement in Georgia and an active member of the Shevardeni society, along with Giorgi Egnatashvili,[2] Giorgi Nikoladze,[3] and his classmate Gaioz Berelashvili.[4] Studying at the gymnasium under the Czech teacher Anton Lukesh, participating in traditional gymnastics mornings[5] at school, and competing in international competitions did not go unnoticed. These experiences led David Javrishvili to decide to devote his future to artistic gymnastics.

|

Cadet David Javrishvili |

David Javrishvili, one of the founders of the Amirani Sports Society and Deputy Head of Training, 1917 |

In 1919, David Javrishvili moved to Kutaisi, which, after Tbilisi, became the centre of Georgian gymnastics.

From 1921 onward, David Javrishvili worked in Batumi for ten years. In 1928, he staged a four-part gymnastic performance, In Ancient Ellada, featuring students from the Batumi Pedagogical Institute, with music by Shalva Taktakishvili and his own libretto. Javrishvili drew inspiration from the history of Ancient Greece, deliberately avoiding a combination of gymnastics and Georgian dance movements, instead paying tribute to ancient Greek art. David was well acquainted with the athletic spectacles of Ancient Greece and sought to present them to the audience in his own interpretation.

It was during this period that he decided to incorporate elements of Georgian folk dance into gymnastics and to perform free exercises set to music. Kuji Dzidzhishvili wrote: “Even in David Javrishvili’s early works, one can see his skill in artistically combining the concise movements of gymnastics with the emotional, spirited techniques of Georgian dance. And while Giorgi Egnatashvili revived the ancient tradition of Georgian physical culture, no less credit belongs to David Javrishvili for restoring the old tradition — the art of the mepunduke (gymnast-dancer).”[6]

The revival of the ancient art of dance and exercise revealed David’s remarkable talent, in which Giorgi Nikoladze played a significant role. It was he who advised David to explore the essence of dance more deeply and to view it through the prism of physical culture, taking the principles of exercise as a foundation. Nikoladze was evidently well-versed in both sports and dance, as well as in Émile Jaques-Dalcroze’s system of rhythmic movement.[7]

In the 1920s, Tbilisi experienced a powerful creative boom. The tours of Ekaterina Geltser, Vasily Tikhomirov, and the barefoot Isadora Duncan were met with great success. It appears that David Javrishvili was strongly influenced by the ballet productions of Nikolai Forger and Mikhail Mordkin. “In 1924, David Javrishvili began studying Georgian choreography, and the gymnast became so captivated by it that he devoted the rest of his life to this field.”[8] While (according to Lili Gvaramadze) the combination of gymnastic and classical dance techniques was still rather vague in David Javrishvili’s imagination, the general outline was already taking shape. As he himself later admitted, this was intentional, since he was not yet familiar with Georgian dance folklore, and his knowledge of Eastern Georgian dance patterns alone was insufficient. Therefore, Javrishvili spent two years in Batumi studying under Stanislav Vakarets,[9] former ballet master of the Tbilisi Opera and Ballet Theatre. He recalled that, as a young man of twenty-seven or twenty-eight, training required great effort and was difficult for him, but his willpower and determination paid off: “Vakarets was pleased with me; he especially liked my leaps,”[10] he later said. Although Javrishvili did not become a professional dancer, his mastery of classical exercises and his intuitive understanding of them helped him develop his own system for teaching Georgian dance. Around the same time, David also began collecting and studying Georgian folk dances.[11]

He deepened his knowledge of Georgian folk dance with the historian Ivane Javakhishvili, and in 1926 organised his first expedition to mountainous Adjara. Javrishvili sought out dancers in the most remote and inaccessible areas of the region. He often joined in the dancing himself in order to better remember the characteristic movements, while also recording the melodies, lyrics of the accompanying songs, and the dancers’ comments. He visited Keda, Khulo, Khikhadziri, and Kobuleti. During this expedition, he studied the Khorumi and Gadakhveuli Khorumi, several Perkhulebi (round dances), Tsangala da Gogona, Women’s Dance, and Sakhumaro (humorous dance). In 1934, he traveled to Upper Svaneti for the same purpose, filming nine variations of eleven dances and taking approximately 1,300 photographs.

After becoming thoroughly acquainted with Adjaran dance folklore, in 1928 Javrishvili opened a choreography studio at the Batumi Pedagogical Institute with an experimental approach. By combining elements of Georgian dance, physical education, and exercise, he created his own system of Georgian folk choreography. The studio had 40 students. As he himself recalled: “I invited ballet master Stanislav Vakarets and ballerina Tamar Balanchivadze to the studio as teachers, and I personally taught Georgian dances. From Georgian folk dances, I staged Perkhuli, Khorumi, Gogona, Sakhumaro, and Women’s Dance.”[12] It was on the basis of this studio that the first Adjaran song and dance ensemble was created. At that time, the combination of singing and dancing on stage was a new concept, which was brilliantly realised by David Javrishvili and choir master Meliton Kukhianidze.

David Javrishvili, ballet master of the Tbilisi Opera and Ballet Theatre

In 1932, David Javrishvili moved to Tbilisi. In 1933, he was appointed ballet master of Georgian operas at the Tbilisi Opera and Ballet Theatre, where he worked for twenty years. Prior to that, in 1931, he choreographed dances for the opera Abesalom and Eteri in the Ukrainian capital of Kharkiv, which brought him great success. In 1937, following the Decade of Georgian Culture and Art in Moscow, Georgian operas entered the repertoire of almost all theatres in the Soviet Union. Javrishvili was the first ballet master to stage Georgian dances in theatres in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Kharkiv, and Odessa, as well as at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow and with the State Dance Ensemble of the Soviet Union. He conducted seminars on Georgian folk dances at choreography schools in Moscow and Leningrad. In 1951, at the Berlin International Festival, and in 1955, at the 5th World Festival of Youth and Students in Warsaw, Javrishvili directed Georgian dancers.

The performance of the Georgian dance troupe at the International Dance Festival in London in 1935, led by Javrishvili, was a triumph. Eighteen European countries participated in the festival, which aimed to present and introduce folk dances. In the Garden Hall, the Georgian dance troupe performed three dances: Khorumi, Ossetian, and Mountain with a Sword. The English press responded enthusiastically to the ancient warrior dance Khorumi, highlighting its ethnographic uniqueness, sculptural expressiveness, and dynamic movements. The Georgian artists also gave concerts in Hyde Park, Regent’s Park, Victoria Park, and Greenwich.

There were no prizes or awards at the festival; each group received a commemorative token and a medal. “It was Javrishvili who presented Georgian choreography in London, ‘devoid of false effect, free, and preserving the purity characteristic of the people.’ ”[13]

London International Festival, 1935.

Standing (left to right): Vano Shagulashvili (medole — drummer); brothers Levan and Sergo Zubiashvili (duduk players); Sergo Noniashvili; Mikheil Chochishvili. Seated: Anton Chikhladze; David Javrishvili; representatives of the Soviet Union — Iliko Sukhishvili and Vladimir Khetagurov.

In 1934, Javrishvili also opened a free choreography studio in Tbilisi, which was soon joined by Maria Perini’s private studio. In 1935, this studio was transformed into a state school, and Javrishvili remained its director until 1952.

After fifteen years of fruitful work, David Javrishvili was dismissed from the school and theatre without explanation, allegedly “at his own request.” Vakhtang Chabukiani was appointed director of the school (the choreography school founded by David has long borne Chabukiani’s name). Despite his deep sorrow, Javrishvili did not give up: he established a choreography department at the Tbilisi Cultural and Educational School, which he led until the end of his life.

David Javrishvili began formulating and expressing his ideas in his works relatively late. Most of his publications appeared in the 1950s: Dance with a Georgian Sketch (1951), Khorumi (1954), Mtiuletian Dances (1957), and Georgian Folk Dance (in Russian, 1965). One of his most notable works from his later period is Conventional Signs for Transcribing Georgian Dance (1961). The author himself wrote:

My system can only represent Georgian folk dances graphically, but who knows, perhaps with the help of further search and other ballet masters, it can be applied to choreographic art, dance movements, and also to the language of classical dance of other peoples. Only then could it be called universal.[14]

The symbols are easy to read, easy to remember, and correspond to the principles of musical notation. The book’s editor, Lili Gvaramadze, writes:

I can say with confidence that David Javrishvili, while preserving the distinctive features and characteristics of Georgian dance, has succeeded in creating a concise notation system. But the most important aspect of this book is not only the synchronisation of musical measures and dance symbols, the accessibility of the system, and the ability to read any choreographic combination from the sheet, but also the fact that the creative principles of David Javrishvili — choreographer, teacher, and scholar — are fully revealed in this work.[15]

David Javrishvili’s works remained unpublished for 60 years. For 20 of those years, his most important work, Dances of Georgian Women, was held by the publisher, and it was only rescued from loss in the 1990s by his daughter-in-law, Nata Javrishvili.

|

Expedition to Svaneti, 1934 |

Expedition to Svaneti, 1934 |

Expedition to Svaneti, 1934 |

In 2018, the State Centre for Folklore published David Javrishvili’s book Georgian Folk Dance, which brings together his previously published works along with a wealth of previously unknown material: Dances of Georgian Women (eight women’s dances); materials from the 1934 Svaneti expedition; and Svan folk dances reconstructed from silent films.

The book is supplemented with archival materials obtained from the State Folklore Centre, the Palace of Arts, and family archives, including:

– the names of approximately 100 Georgian dances;

– a classification of dance genres and forms proposed by Javrishvili;

– verbal, graphic, and schematic descriptions of Davluri, Mtsq’emsuri, Guruli Perkhuli, Mkhedruli, Gandagana, and Saokhunjo dances;

– graphic and choreographic drawings of 15 Georgian dances, including Mtsq’emsuri, Otlarchopa, Salkhino, Samaya, Shushpari, Kal-Vazhta Lkhini, Svanuri Suita, Megobroba, Doluri, Sakortsilo, and others.

Most of the graphic drawings of these dances are original.

The publishing team of the book was encouraged not to limit itself to merely mentioning the 1934 Svaneti expedition, but also to incorporate silent film material. As a result, the book includes fourteen Svan dances, choreographically described (verbally) and notated with Svan-Georgian texts — a significant novelty that enhances the value of this publication. These dances are: Lashgari, Biba, Dideba Targzeles, Tamar Dedpal, Lamurgvalyash, Mirmikela, Rostom Chabigv, Q’ansav Q’ipiane, Cheq’arams-Choq’urams, Givergila, Kasletila, Lazhgwash, Dala Kozhas Khelghvazhale, and Reli.

One important aspect is David Javrishvili’s connection with the State Folklore Centre (then the House of Folk Art): he was a permanent member of the choreography section and actively participated in the preparation of competitions, and it was there that his fundamental work, Dance in Georgian Style (Georgian Dance), was first discussed. In 1941, the House of Folk Art commissioned him to compile a terminology of Georgian dance. David Javrishvili introduced numerous gymnastic terms to Georgian choreography.

His archive shows that Javrishvili did not complete his work on the dictionary. While working on Georgian Folk Dance, drawing on Javrishvili’s research and archival materials, and following his example and style, I undertook this extremely challenging task (the publication includes more than 400 lexemes) and, as far as possible, completed the work begun by the researcher, although much remains to be done in this area.

Georgian State Song and Dance Ensemble.

Choreographer Davit Javrishvili in motion while staging Khorumi, 1950s.

David Javrishvili’s personal archive, stored at the Palace of Arts, contains approximately 3,000 items. The complete processing and publication of this archive remain a task for the future; however, the archive catalogue and its electronic version, published by the Palace of Arts, will be of great assistance to researchers interested in the life and work of Javrishvili.[16]

Since this great man, both professional and citizen, wrote almost nothing about himself, let us once again listen to Lili Gvaramadze: “A deep knowledge of dance folklore, refined taste, and the ability to mould dance into a highly artistic, complete form — these qualities of choreographer Javrishvili run like a red thread through all his work, contributing to the creation of Georgian theatrical choreography imbued with a unique folk flavour.”[17]

David Javrishvili died in 1971. He is buried in Tbilisi, in the Didube Pantheon of Writers and Public Figures.

[1] Gvaramadze, Lili. 2023. Kartuli Khalkhuri Tsekva [Georgian Folk Dance; monograph on David Javrishvili]. Tbilisi: Favoriti Publishers, p. 458.

[2] Giorgi Egnatashvili (1885–1962) was an educator and a key organiser of the sports and physical education movement in Georgia, as well as one of the founders and leaders of Shevardeni. In 1909, he graduated from the Higher Gymnastics Courses in Prague. In 1912, he took first place as part of the Tbilisi team at the World Congress of the Sokol Sports Society. He worked at the Physical Culture and Polytechnic Institutes. The Central Children’s and Youth School of the Tbilisi Department of Public Education is named in his honor. He is buried in the Didube Pantheon.

[3] Giorgi Nikoladze (1888–1931), the son of Niko Nikoladze, was himself a mathematician, the founder of athletic gymnastics and mountaineering in Georgia, a founder of the Georgian Geographical Society, and a professor. From childhood, he studied gymnastics under the Czech teacher Anton Lukesh and participated in international competitions. In 1913, he graduated from the St. Petersburg Technical Institute. From 1918 to 1921, he served as Deputy Minister of Industry and Trade of the Georgian Democratic Republic. In 1928, he defended his dissertation at the Sorbonne. He later taught at Tbilisi State University. He is buried in the Didube Pantheon.

[4] Gaioz Berelashvili (1892–1937) was a Georgian gymnast and one of the founders of artistic gymnastics in Georgia. He studied at the Faculty of Chemistry at Moscow University. In 1912, he took first place at the VI Jubilee Rally in Prague. In 1937, he was executed on charges of participating in a counter-revolutionary organisation. He was posthumously rehabilitated in 1956.

[5] During Javrishvili’s studies at the gymnasium, gymnastic matinees were held with his participation.

[6] Gvaramadze, 2023, p. 460.

[7] Émile Jaques-Dalcroze (1865–1950) was a Swiss composer and educator. He developed a rhythmic-plastic system of musical education aimed at expressing music and rhythmic elements through bodily movement. Schools based on this system were established in Stockholm, London, Paris, Vienna, and Barcelona. In 1920, institutes following Jaques-Dalcroze’s method were founded in Moscow and Petrograd.

[8] Dzidzhishvili, Kuji. 1969. “Giorgi Nikoladzis Mosagonari” [In Memory of Giorgi Nikoladze]. Tsiskari 4: 100–109.

[9] Stanislav Felix Vakarets was a ballet master and teacher who worked at the Tbilisi Opera and Ballet Theatre in the 1910s. On 5 February 1919, Dmitry Arakishvili’s opera The Legend of Shota Rustaveli was staged, with choreography by Vakarets and direction by Al. Tsutsunava. Despite Vakarets’s name appearing on the posters, some researchers doubt that a non-native choreographer could have staged the Georgian dances. It is therefore believed that Vakarets was assisted by Alexei Alexidze, who at that time was responsible for staging Georgian dances at the Opera and Ballet Theatre (See: Samsonadze, Anano. 2022. “On the Historical‑Gender Transformations of the Dance ‘Samaia.’” Women and Arts: International Journal of Arts and Media Researches 2 (12): 386‑397.)

[10] Gvaramadze, 2023, p. 460.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Javrishvili, David. 2018. Kartuli Khalkhuri Tsekva [Georgian Folk Dance]. Tbilisi: Samshoblo, pp. 686–688.

[13] Gvaramadze, 2023, p. 465. For detailed materials on the London festival, see Javrishvili, 2018, pp. 673–676.

[14] Javrishvili, 2018, p. 61.

[15] Gvaramadze, Lili. 1964. “Koreograpi, metsnieri, pedagogi” [Choreographer, Scientist, Pedagogue]. Vecherny Tbilisi, 25.

[16] State Museum of Theatre, Music, and Choreography of Georgia. Catalogue of Manuscripts and Archival Documents. Book III. David Javrishvili, pp. 178–344.

[17] Gvaramadze, 2023, p. 466.

.jpg)