Georgian Folk Instrument Orchestra

Instrumental music is a significant element of Georgian musical folklore, with diverse instruments and tunings present across almost every region of Georgia. Traditionally, Georgian instruments primarily accompanied singing and dancing, and at times served as signalling tools. Instruments sometimes accompanied work-related activities and also occasionally acquired sacred significance, being used in various cultic-religious rituals, such as healing the sick, incantations, and ceremonies associated with the cult of the dead.

The history of the Georgian folk instrument orchestra is connected to some unpublished facts, which I will discuss below. However, it should be noted that the ensemble of folk instruments is not foreign to traditional Georgian music life. Manana Shilakadze discusses the practice of instrumental ensembles - mtsqobri [1], noting that: “1) the traditional Georgian instrumental ensemble combines two different instruments; 2) its repertoire consists of dance melodies.” [2] According to Otar Chijavadze, among stringed instruments, the chonguri is used in with more than one played together, while the chiboni is used among wind instruments, and the doli and daira are used among percussion instruments. [3] The ensemble of the chonguri and doli is confirmed in Achara, the panduri and daira in Kakheti and Tusheti, and the doli and chiboni in Achara. The pair of stringed instruments changi and chuniri are found in Svaneti.

The formation, performance, and development of musical instruments are significantly influenced by social and cultural processes. It is interesting to consider when the folk instrument orchestra was created and how the ongoing processes impacted it. The USSR's economic policy of collectivisation, which unified private households into large collective farms, significantly influenced Georgian folklore. This collective mentality and social structure also influenced folklore. Large, mass choirs were formed during this time, and it was in the 1930s that the idea of creating a folk instrument orchestra was born, aimed at larger audiences. It should also be noted that the existence of large choirs and orchestras somewhat impacted the traditional forms of performance, and, as a result, the instrumental ensemble could be said to have been replaced by the orchestra.

For example, the simultaneous use of several chonguris, which is a phenomenon of the 1920s-30s, is linked to the names of the Sichinava brothers in Samegrelo and Avksenti Megrelidze in Guria. In 1927, Avksenti Megrelidze formed a women's chonguri group, and later, other instruments were added to this ensemble. The first example of chonguri and panduri being united into one ensemble occurred in his choir. The performance of both eastern and western Georgian stringed instruments together represented a new development in folk music performance. In one of his articles, the choirmaster wrote: “Currently, our ensemble includes the four-stringed chonguri from western Georgia and the three-stringed panduri from eastern Georgia... The union, combination, and harmonious blending of all Georgian folk musical instruments is the main goal of my work. My goal is to achieve the blending of the chonguri, panduri, chianuri, stviri, Svan changi, doli, and salamuri as soon as possible.” [4]

He successfully realised his goal realised in the 1930s. We can consider Avksenti Megrelidze’s experiments as attempts to create a folk instrument orchestra. It is noteworthy that creating the orchestra was not Avksenti Megrelidze’s primary goal, since such an event was foreign to Georgian rural life. It should be noted that Megrelidze was satisfied with the potential of traditional instruments and did not attempt their reconstruction. [5]

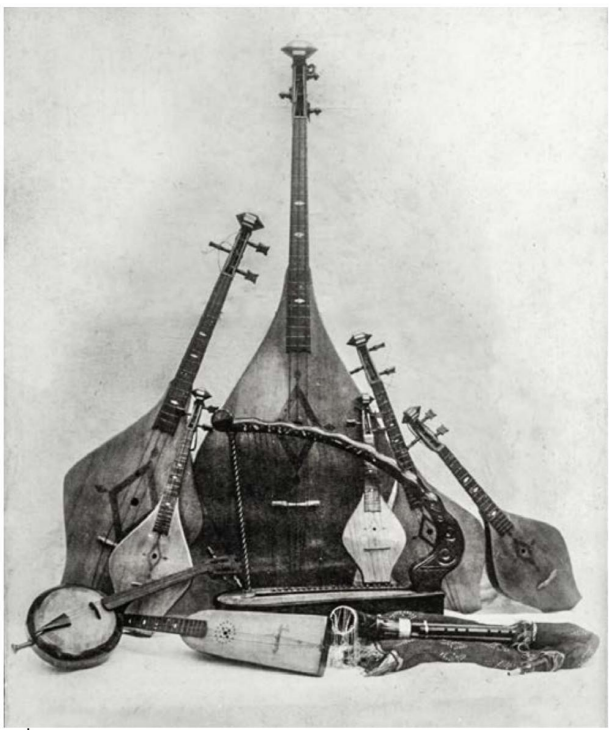

Have you heard of Kirile Vashakidze? Vasil Tamarashvili? It is precisely their names that are linked to the establishment of the Georgian folk instrument orchestra. In 1937, the esteemed artist Kirile Vashakidze collected instruments from various regions, renewed some of them, and founded the Georgian Folk Instrument Orchestra. Alongside the orchestra Vashakidze established at the Tbilisi Architectural Technical School, musician Vasil Tamarashvili created another folk instrument orchestra using his own reconstructed instruments. [6]

What distinguished the two orchestras? The one founded by Kirile Vashakidze somewhat justified its name (Georgian Folk Orchestra), as the folk instruments in his orchestra largely retained the timbre, shape, and character of the instruments. On the other hand, Tamarashvili's orchestra was entirely composed of instruments he had reconstructed. However, there were also similarities between them, as both orchestras consisted of chromatic instruments instead of diatonic ones, as they believed that folk instruments were primitive and needed development. Furthermore, the need to harmonise instruments from different regions created the necessity for some changes. Therefore, both altered the arrangement and temperament of the instruments.

It is interesting to note what Kirile Vashakidze wrote in the newspaper Musha: “Work on Georgian folk musical instruments is lagging behind. We still haven’t mastered these instruments for conveying modern melodies: their use still hasn’t gone beyond simple ensemble forms, where melodies are not played by the instruments themselves, but by the singers, with the instruments only providing simple accompaniment.” [7]

In Vasil Tamarashvili’s orchestra, reconstructed instruments were presented. He modified the tuning and range of five Georgian folk instruments—chonguri, gudastviri, panduri, chuniri, and changi, though he preserved their external appearance, except for the chuniri, which was given a classical form. Vasil Tamarashvili described the arrangements of his reconstructed instruments: “Georgian three-part singing is its natural feature, and I transferred this to instrumental music. In an ensemble of chonguris arranged in six voices, we primarily took three voices and then doubled them in octaves: the pure voice chonguri is krini, then chonguri tkma, chonguri zili, chonguri modzakhili, chonguri bani, and chonguri dvrini [these are all names of voices in Georgian singing - Ed.]. All these are tuned with an interval of a fifth between instruments, and their strings tuned in fourths. The range of each extends up to two and a half octaves and has three gut strings.” [8] Gudastviri [Georgian type of bagpipe] was also retuned/rearranged in three ways. The eight-holed gudastviri was intended for melody playing, while the other two produced only drones. Therefore, unlike Vashakidze's orchestra, Tamarashvili's orchestra consisted of fully modified instruments. His aim was to perform not only folk songs but also pieces of Georgian and Western classical composers, whose arrangements he created for his orchestra, and the scores for these arrangements are preserved in the State Folklore Center of Georgia.

We are drawn to Avksenti Megrelidze’s opinion about Tamarashvili's reconstructed chonguri. “This instrument, what is referred to as the chonguri, is not truly a chonguri. Externally, it still doesn’t satisfy me. It reminds me of a man wearing a chokha [traditional Georgian male attire] but with a Russian hat on. The temperament of the reconstructed chonguri is entirely different. It does not resemble the folk chonguri at all.” [9] I believe that, like the chonguri, other transformed and reconstructed instruments would have lost their original form. Therefore, an orchestra made up of altered instruments required careful observation and testing over time.

On January 3, 1940, a meeting of the commission for the review of the two orchestras was held at the Department of Arts Affairs. A jury was formed to evaluate their functioning and significance. It was widely agreed that Kirile Vashakidze's orchestra, created with traditional Georgian folk instruments, adhered more closely to folk principles, retaining the folk timbre and form, which Tamarashvili’s reconstructed orchestra was seen to lack. This view was shared by: Grigol Chkhikvadze, Avksenti Megrelidze, Andria Balanchivadze, Giorgi Khakhanashvili, Vladimer Chumburidze, Pavle Khuchua, Pavle Kandelaki, Akaki Paghava, Grigol Nutsubidze, and Grigol Kokeladze. Their view stemmed from the concern that the reconstructed instruments might have had an impact on pure Georgian folk instruments, and even replaced them. Furthermore, according to Grigol Chkhikvadze, Vashakidze's orchestra should have included other Georgian folk instruments, such as the saqviri, tsintsila, ebani, buki [10], and others. [11]

Ultimately, the jury decided to dissolve Vasili Tamarashvili’s orchestra, as only Kirile Vashakidze's orchestra had preserved the principles of folk instruments, their distinctive Georgian timbre, form, and content. [12]

In an interview with Omar Kelaptrishvili’s wife, Tsimi Kelaptrishvili, we learn that, as a result of this victory, Kirile’s orchestra continued to exist for several more years. [13] However, as Tsimi sadly notes, “The people in charge weren’t the type to pay attention to this matter, and this orchestra, which had surpassed Tamarashvili’s orchestra, was eventually dissolved a few years later. Yet, in 1953, a letter was published in the newspaper Komunisti, requesting the restoration of Kirile Vashakidze’s folk instrument orchestra. Fortunately, this letter received positive responses, and indeed, Vashakidze’s orchestra was re-established and revived, eventually becoming part of the state ensemble now known as Rustavi. It was in this second version of the orchestra that Omar Kelaptrishvili also played.” From Tsimi's story, it appears that Kirile’s second orchestra faced the threat of dissolution once again. “It probably needed patronage, and Kirile could not manage it alone. Kirile approached many for help, but still, the folk instrument orchestra was disbanded.”

Although Kirile’s and Tamarashvili’s orchestras were eventually dissolved, history was written from which we understand that, on one hand, folk instruments have great potential to perform independent melodies. On the other hand, there is also the possibility that they could exist in an orchestra. Nevertheless, I believe, the creation of modified and developed instruments does not diminish the importance or archaic essence of traditional folk diatonic instruments. These orchestras, one could say, played the role of experimental innovative projects in their time. From a traditional performance perspective, the simultaneous sound of several instruments from different groups limited each instrument’s individuality, which, of course, hindered the important characteristic of live music — improvisation.

The history developed around the folk instruments in the last century raises many questions: To what extent is it valid to unify instruments from different regions into a single orchestra? How compatible are the timbres of different instruments? What is the repertoire of a folk instrument orchestra? And, in general, what has the modification or change of the instruments added to, or taken away from, Georgian traditional music? And to what extent has the new performance aesthetic of these instruments enriched the Georgian traditional repertoire? These questions are addressed to the readers of the article and require in-depth future research.

[1] Otar Chijavadze, in his encyclopedic definition of the term ‘mts'q'obri', refers to it as an orchestra or an instrumental ensemble: “The traditional Georgian instrumental mts'q'obri is composed of two instruments: one stringed or wind instrument, and the other—percussive.” (Chijavadze, Otar. 2009. Sak'ravebi dzvel Sakartveloshi [Instruments in Ancient Georgia]. Tbilisi: Georgian Folk Song and Instrument State Museum, 44-45).

[2] Shilak'adze, Manana. 1970. Kartuli khalkhuri sak'ravebi da sak'ravieri musika [Georgian Folk Instruments and Instrumental Music]. Tbilisi: Metsniereba.

[3] Chijavadze, Otar. 2009. Sak'ravebi dzvel Sakartveloshi [Instruments in Ancient Georgia]. Tbilisi: Georgian Folk Song and Instrument State Museum.

[4] Moists'rapishvili, Nat'o. 2008. Avksent'i Megrelidze. Tbilisi: Sakartvelos Matsne, 168–172.

[5] K'otrik'adze, Sopik'o. 2015. “Mts'q'obidan khalkur sak'ravta ork'est'ramde." [From an Ensemble to a Folk Orchestra] In Khelovnebatmtsodnobiti Et'udebi [Studies in Art Criticism], Vol. VI, 398. Batumi: Khelovnebis Universit'et'i.

[6] K'elap't'rishvili, Natela, and Omar K'elap't'rishvili. 2023. Kartuli salamurit dap'q'robili msoplio [The World Conquered by the Georgian Salamuri]. Tbilisi: Universali.

[7] Vashak'idze, K'irile 1937. “Kartuli khalkhuri musik'aluli inst'rument'ebis ansambli” [The Georgian Folk Instrumental Ensemble]. Musha, 3.

[8] Republican House of Folk Art, Department of Art Affairs. 1937. “Protocol #5, Meeting on the Creation of the Georgian Folk Reconstructed Musical Instrument Orchestra.” Materials held in the National Archive and the Folklore Centre Archive, Fund N 130, File 1, Case 5. 2.

[9] Republican House of Folk Art, Department of Art Affairs. 1937. “Protocol #5, Meeting on the Creation of the Georgian Folk Reconstructed Musical Instrument Orchestra.” Materials held in the National Archive and the Folklore Centre Archive, Fund N 130, File 1, Case 5. 4.

[10] Saq'viri (Horn) – a high-register wind instrument.

Ts'ints'ila (Cymbal) – an ancient Georgian percussion instrument.

Ebani – a synonym for changi and k'nari (Harp); sometimes it also refers to a daf (Tambourine); an ancient string instrument.

Buk'i (Trumpet) – a military signalling instrument.

[11] Republican House of Folk Art, Department of Art Affairs. 1940. “Protocol #32, Meeting for the Review of the Georgian Folk Orchestra.” 1.

[12] Ibid., 5.

[13] Omar K'elap't'rishvili — People's Artist of Georgia, a virtuoso performer on the salamuri, and a soloist of the Rustavi ensemble. He founded the ensemble Iavnana, which was later renamed K'elap't'ari in his honor.

.jpg)