Georgian Chant: From the Depths of History to the Present Day

“Chant is the voice of an angel before the throne of God: Holy, holy, holy, Lord of hosts. If you don’t chant to God, it doesn’t count as chanting.” (1).

As suggested by this quote from Ioane Batonishvili, the word “chant” in the Georgian language, galoba, implies the sound, the melody of addressing God, and is thus separate from “song,” which implies secular music.

|

Grigol Khandztseli, 18th century miniature |

The author of the tenth-century Life of Grigol Khandzteli, Giorgi Merchule, noted that

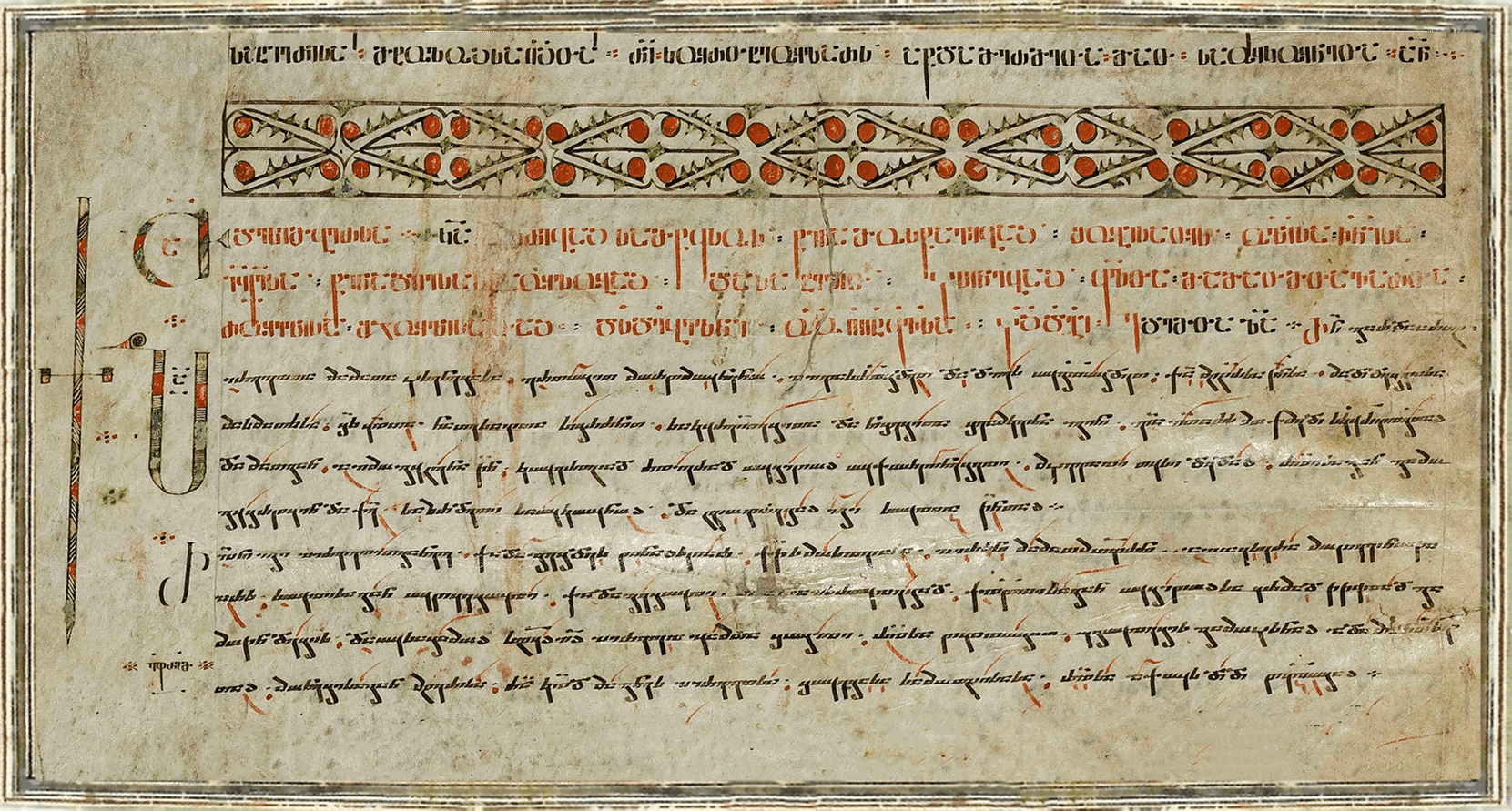

As we see, for Merchule, the borders of Georgia—“mighty Kartli”—are defined by the Georgian language of worship. In support of his point, he discusses Georgian chanting, which further suggests its truly ancient origins. The rise of Georgian chanting begins from the period of the establishment of monastic life in Georgia in the sixth century, by the monks known as the Thirteen Assyrian Fathers. The longevity of Georgian chant is documented in many ancient Georgian manuscripts, such as the seventh-century Khanmet Lectionary, the eighth-century Jerusalem Lectionary, and the Ch’il-Et’ratis Iadgari (“compilation” or “treasury”), dated from the seventh to ninth century, all of which contain texts of various types of liturgical hymns. Along with these written treasures, of particular value are the manuscript collections containing neumes, a type of musical notation used for transcribing Georgian chants. These include the tenth century Iadgari of Mikael Modrekili, the Alaverdi Irmoi, and others. |

As with Georgian folk songs, the musical structure of Georgian chants is polyphonic—more specifically, three-part. The oldest written information about the three-voice structure of Georgian chant can be found in the comments of the eleventh-century Georgian philosopher Ioane Petritsi, which accompany his translation of Proclus’s Elements of Theology. In order to explain the dogma of the oneness of the Trinity, Ioane Petritsi, along with various analogies, includes the voices in chanting:

“I will tell you of the union of the three, united into one: mzakhr, zhir, and bam.” (3).

These terms have been interpreted to refer to the three voices in a Georgian chant or folk song.

|

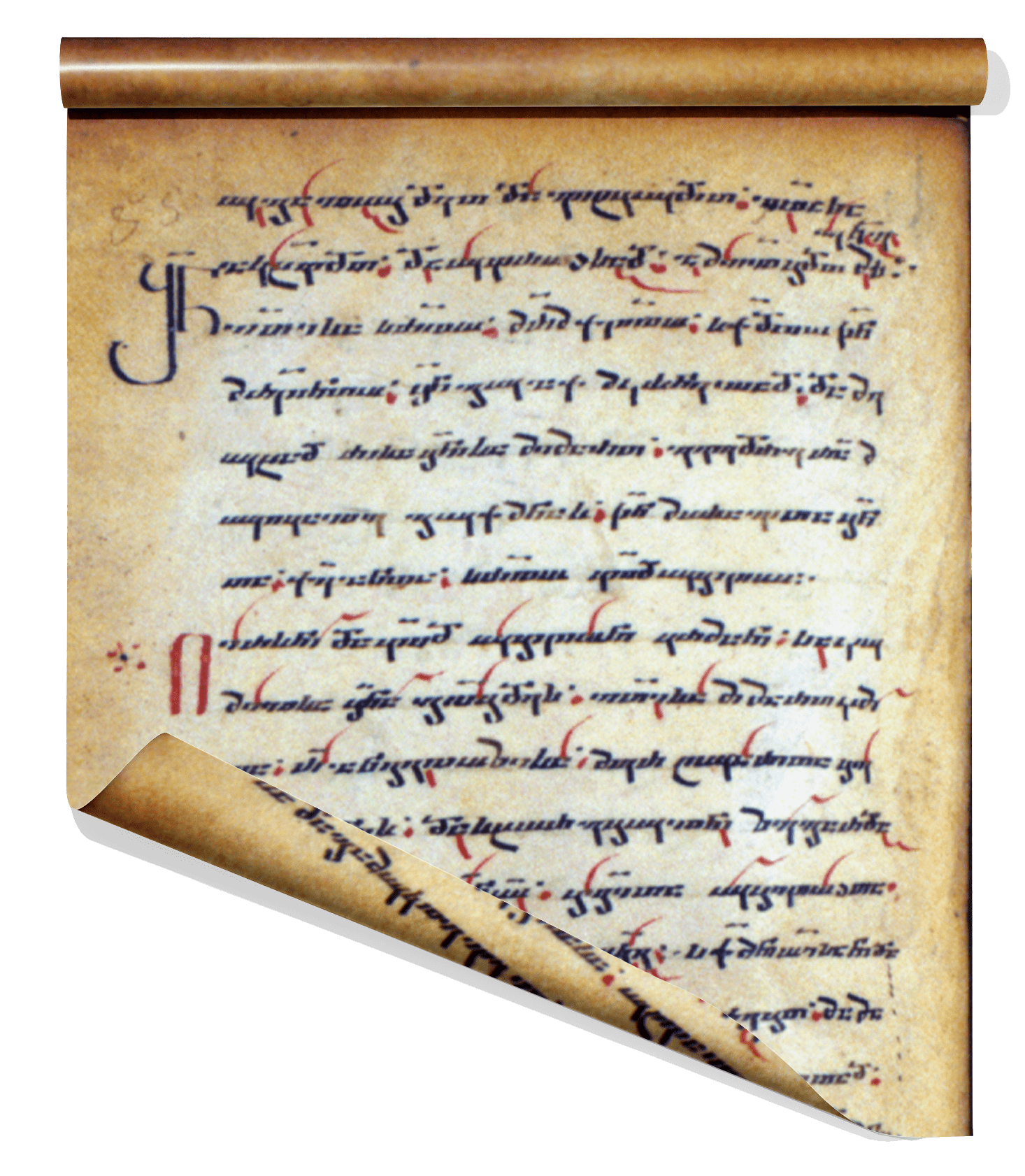

Alaverdi Irmos |

In his book on the history of ancient Georgian literature, Korneli Kekelidze emphasizes the importance of centers of learning attached to churches and monasteries, as well as independent schools. This view on church literature perfectly fits with the history of the development of Georgian church music—that is, chanting—and the formation of chanting school traditions. Some of the oldest centers of Georgian chanting, both in Georgia and abroad—for instance, monasteries at Mar-Saba, Mount Sinai, Tao-Klarjeti, Mount Athos—created a foundation for Georgian chanting, which was preserved in the rich traditions of the Gelati, Svetitskhoveli, and Shemokmedi monasteries. When discussing Georgian chants, along with the original Georgian or translated texts, the three-part musical language of the chants is implied. In the old collections with neume notation, only the top voice was notated, since the canonical stability of the chant melody is manifested in this voice part. As a rule, the modzakhil (second voice) and bani (bass) would then tune to the top voice, because again, in the words of Ioane Batonishvili:

Each monastic center or chanting school had its own set of rules and regulations. It was in this way that the common canonical tunes acquired musical diversity and intricate and complex harmonies.

|

The “Golden Age” of Georgian history is also distinguished by a rise in Georgian chanting. In David Aghmashenebeli's Galoban sinanulisani (Hymns of repentance), the mention of melodies indicated that the hymns were chanted and confirms the special attention paid to the art of chanting at that time, both in the church and at the royal court. The hymn “Shen khar venakhi” (You are the vine), which has become a symbol of Georgian chanting, is also a creation of the Golden Age.

Unfortunately, the difficult period in Georgian history that followed, was marked by continuous invasions, conquests, and the persecution and destruction of Georgian Christianity, had a severe impact on the life of the country, its culture and, consequently, Georgian chanting. Many treasures were destroyed, likely including more than a few precious manuscripts of Georgian chants.

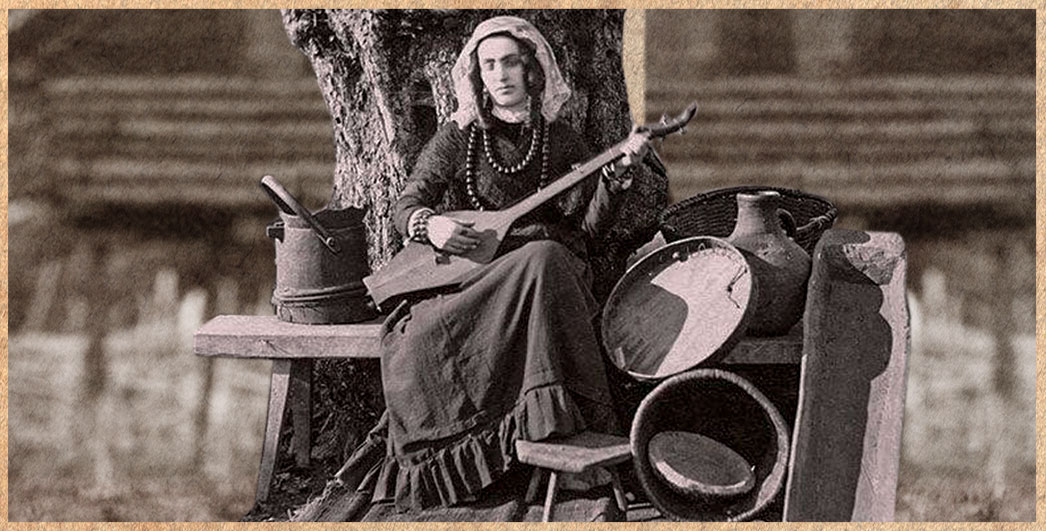

Nevertheless, in the eighteenth century, an active concern arose for the preservation of Georgian identity and culture, including Georgian chanting. Many hymns to Georgian saints were created during this period. Learning to sing was considered an honorable practice, even in the royal family. Unfortunately, subsequent historical events put not only the chanting tradition but the entire country in existential danger.

|

King David the Psalmist |

In 1801 Russia abolished first the state of Georgia and then, ten years later, the autocephaly of the Georgian Church. Georgian spiritual and material treasures were destroyed, looted, and disappeared in the hands of exarchs with aspirations towards Russification. Worship in Georgian and Georgian chanting were also banned. This situation gave rise to the national liberation movement in Georgia, whose main task was to save Georgian language, history, and culture, including Georgian chants. A chanting restoration committee was formed in the 1860s. Through their efforts it became possible to transcribe thousands of hymns. The hymns performed by the still-surviving masters of Georgian chant were notated by Pilimon Koridze, Vasil and Polievkto Karbelashvili, Razhden Khundadze, and Ekvtime Kereselidze. This was the most common and most straightforward way to save Georgian chant. Georgia’s independence, once it broke free from the clutches of the Russian Empire, lasted for only three years. The Soviet regime that took over in 1921, officially atheist, further hindered Georgian church life and, consequently, the state of Georgian chanting. |

Until the 1960s, traditional Georgian chants were almost forgotten. Soviet censorship was still active in the post-Stalinist period. Thus, the concert of Georgian chants held by the ensemble Gordela in the late sixties at the Tbilisi State Conservatory was a bold step. They were followed by the ensemble Rustavi, who included chants alongside folk songs on gramophone records. For protection against censorship, however, the chant names were omitted on the records’ track list, replaced instead with the word “chorale.”

Despite the growing interest in chanting during this period, the great treasures preserved in notated manuscripts were not unearthed until the late 1980s. The study of this invaluable material of traditional chanting and its introduction into the practice of worship was the special contribution of the choir of the Anchiskhati Cathedral in Tbilisi, which formed in 1988 and later came to be known as the Anchiskhati Choir. The work of this group set an example and garnered many followers in Tbilisi and other regions. By the decision of the Holy Synod, the old, traditional ecclesiastical chanting became obligatory during the church services (2003, 2010).

Despite this decision of the Synod and the revival of numerous gems of Georgian Christian music tradition, there are still many obstacles that must be overcome in order to fully develop this discipline.

References:

- 1.Batonishvili, Ioane. 1991. Khumarsts’ Tbilisi: Kalmasoba. p 519.

- 2.Kekelidze, Korneli. 1980. Dzveli kartuli lit’erat’uris ist’ [History of Ancient Georgian Literature] Volume I, Tbilisi. p 32.

- 3.Petritsi, Ioane. 1937. Works.Vol. II. “Explanation of Proclus. Diadochus and the Platonic Philosophy”. Tbilisi: University Press Publisher. P. 217.

- 4.Batonishvili, Ioane. 1991. Khumarsts’ Tbilisi: Kalmasoba. p 524.

Cover image: The Iadgari of Mikael Modrekili