Georgian Dance Speaks to Us in the Language of Myth

When researching traditional Georgian culture, one gets the impression that people lived together with gods. The traces of artistic thinking—which at the earliest stage of human development manifested as myth and incorporated magical elements and rituals as a means of achieving harmonious existence—can to this day be found in the art of Georgian traditional dance. Georgian dance preserves the plasticity of the ritual language, which people used to speak to their archaic environment.

Georgians, like many ancient peoples, used dance to connect with powerful cosmic energy, which was necessary to overcome difficult stages in their lives. They danced not to spend energy, but rather to gain it, to win the heart of the Creator, to attract fertility, and to win the battle against evil.

It is generally known that collective dance can generate a surprising feeling of completeness, communion with the greater whole, and a surge of energy can be felt that can make each performer even stronger. It is worth noting that people used to dance in difficult times: during war, famine, or other calamities. It seems that the Mossynoeci, an ancient tribe commonly seen as proto-Georgian, used to dance like this before battle, which surprised the Greek commander Xenophon.

According to ancient historians of the Hellenic period, the Chalybes sang and danced before their enemies. Likewise, the sea-faring Mossynoeci who became Xenophon’s allies—they helped the Greeks get across a river with three hundred boats and warriors—would line up before meeting an enemy, one after another, and then march into battle with their feet moving to the rhythm of song, like a chorus of singers and dancers. The author also noted the unique form of the Mossynoeci’s singing and dancing.

For ancient humans, fighting and defeating the enemy, in a kind of divine hunt, was a symbol of an all-encompassing idea of cosmogony. Before stepping into chaos, i.e., into a battle, it was necessary that the person perform a ritual, a symbolic repetition of the act of creating the universe. Performing the ritual, which involved song and dance, would ensure the needed and desired victory over the enemy.

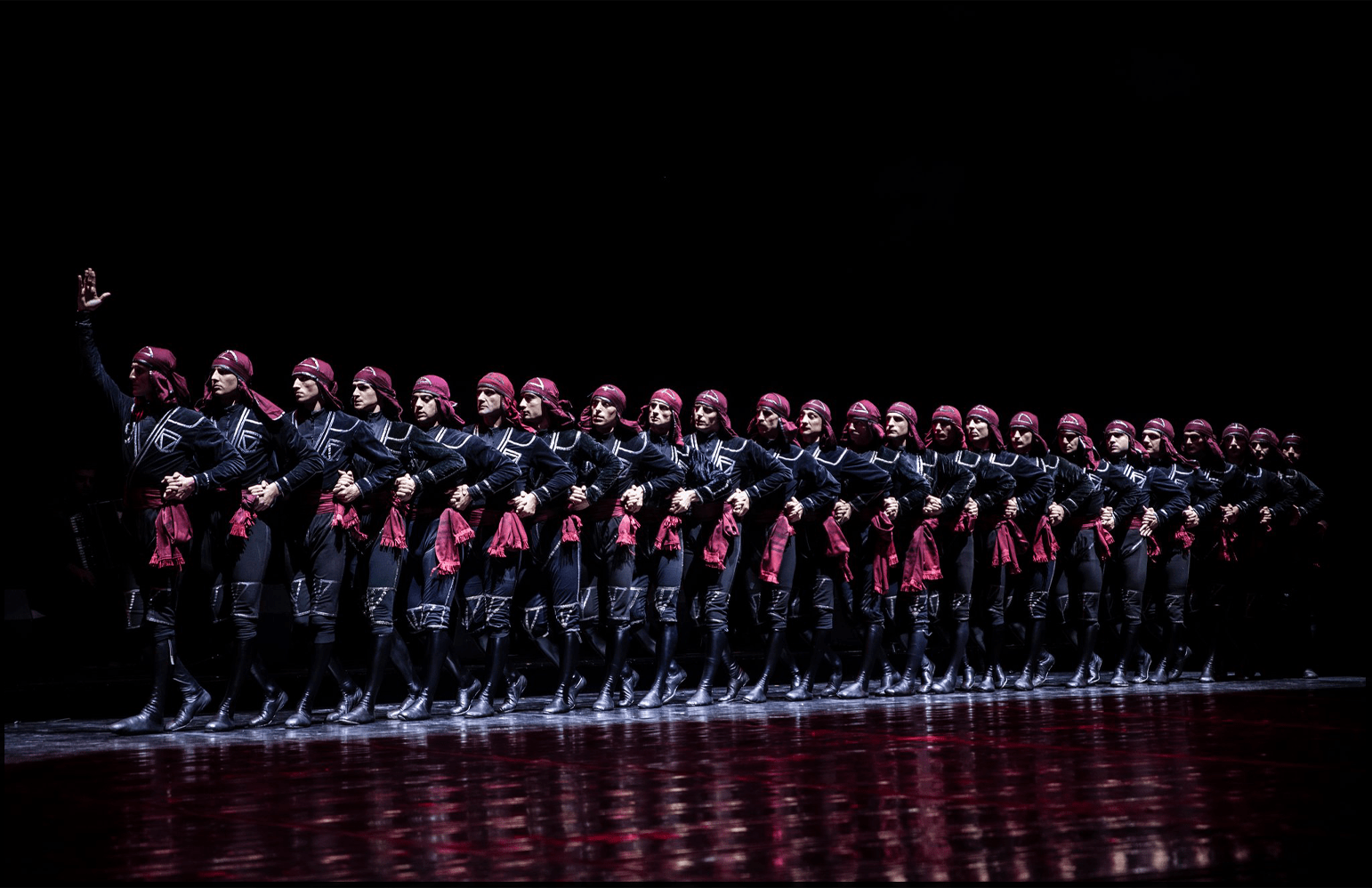

The ancient ritual mentioned by Xenophon reminds us of the modern Georgian dance khorumi. The fierce character of the khorumi also reflects a confrontation with the unknown, with chaos, which implies the inevitable victory of goodness and light.

Danced hunting—the dance of hunters—manifested differently in different world traditions, has a place in folk choreography of many nations of the world. Georgian folk choreography has preserved fragments of such dances to this day.

Historically, it is known that the ancient Georgians paid a lot of attention to events related to the movement of the sun. The cult of the radiant sun was based on the regenerative power of nature. Agricultural practices followed the sun and the solar year. Barbaroba, i.e., the “birthday of the sun,” as well as the calendar year, corresponded with the solstice, and predictions for the coming year were also made according to this day.

The Georgians’ worship of the sun is also mentioned in ancient Greek accounts:

“The ship Argo approached Circe’s home on the island of Aeaea, where stood the dwelling-place of early Dawn (Eos) and her dancing-lawns, and where Helios (the sun) rises.” (1).

It can be seen that for the Greeks, Aeaea—that is, the ancient region known as Kolkheti, today in western Georgia—was the land of the rising sun, because it was located in the east, and they worshiped the cult of the sun, which was especially celebrated with singing and dancing.

Ensemble from Kvemo Svaneti, directed by Ioseb Mukbaniani. Archive of the State Folklore Centre

Evidence of sun worship has reached the present day in Georgian mythology and folklore. Presumably, the origins of the folk song and round-dance (perkhuli) “Lile” can be traced to this cult. According to some theories, this is reflected both in its choreographic form—the circle, a solar symbol—and the direction of movement—facing east and moving counter-clockwise—as well as in the lyrics. Despite the fact that, after the Christianization of Georgia, song texts were also partially Christianized, in “Lile,” at least, the ancient religious-mythological symbolism is preserved, as confirmed by the words and phrases that have survived there. These include: the surrounding fence (ancient people believed that a fence surrounded the world), the golden column (a symbol of the sun), cups (sacred ritual vessels), a fortress (a cosmogonic symbol of the center of the universe), hawks, ibexes, bulls, rams, horns (sacred game, avatars of deities). “Lile,” a Svan ceremonial hymn, is thus one of the oldest samples of Georgian choreographic, musical, and verbal folklore.

The connection to astral symbols and their movement is reflected in the one-, two-, and three-circle formation of the Gurian perkhuli “Partsa.” A one-circle dance signifies the design of the sky and the sun. The movement of the sun and the moon is reflected in the two-circle arrangement of the perkhuli. And in the case of three concentric circles moving in opposite directions, it symbolizes the whole world, with the moving sky, planets, and stars.

Trialeti silver cup

Georgian folk dance, which still amazes the world with its stage performances, must have been first conceived in the second or third millennium BCE. To confirm this, researchers have been analyzing archaeological artifacts found in Georgia on which dance scenes are depicted. Examples include the silver chalice and bronze belt of Trialeti (second millennium BCE); ithyphallic statues found in Rioni, Kavkavi (Vladikavkaz), Dagestan and Khevsureti (first millennium BCE), the bronze belt of Nabaghrebi, and the pitcher of Samadlo.

The mytho-ritualistic interpretations that arose among ancient civilizations regarding the central questions of humanity had a distinct influence on the art of Georgian dance. The ancient myths concerning the creation of the world were the foundation for the rituals of ancient people. Choreography is not a separate entity, but a fundamental and necessary element of these rituals.

Thus, Georgian dance speaks to us in the language of myth. Its form and content include not only the history, character, nature, and customs of this ancient people, but also mythology, cosmogony and those magical-religious aspects that make an indelible impression, captivate, and unconsciously influence the viewer to this day.

References:

- 1.Urushadze, Akaki. 1993. Kutaisi in Greek and Roman Sources. (1. Review. Georgian translations of Greek-Latin texts with notes), Tbilisi: Tbilisi State University Press. p. 17-20).

Cover image: Ensemble Sukhishvili, "Khorumi". Photo by Zuka Pirtkhalashvili.