The Ancient History of the Shepherd-Boy’s Salamuri

Many people may not know this, but one of the oldest musical instruments ever found in Georgia is an ancient reedless flute—known in Georgian as a salamuri—made out of swan bone. Discovered in 1938 in the municipality of Georgia’s old capital, Mtskheta, this tiny object, just 199 millimeters in length, has preserved many secrets of Georgian life and music. The great scholar Ivane Javakhishvili called it “a shepherd-boy’s salamuri.” Why? Because the instrument was found in the grave of a teenager, along with other household items and animal skeletons.

Ivane Javakhishvili and Simon Janashia in Armazi, during archaeological excavations, 1940

Made from a swan’s barrel bone, this salamuri dates back to fourteenth or fifteenth century BC. If we consider that the instrument is quite technologically sophisticated, that it was placed in the grave of a shepherd boy as an important and necessary item, and that flutes made of animal bones, including swans, are well-known in the ancient world, we must assume that the history of bone salamuri in Georgia goes back much further than 1300 BC. Bone salamuris were later found during other archeological excavations in Georgia, and the professors Grigol Chkhikvadze and Manana Shilakadze conducted extensive research on them.

Among Georgian folk tales, an especially beloved and popular one is “Ts’ikara,” which tells the story of a friendship between an orphan boy and a red bull. Many may be oblivious to the fact that this fairy tale has preserved precious information about the existence of two kinds of salamuris. Yes, Georgians used to have two types of salamuri: one for joy and one for sorrow! This means that they would play different salamuris depending on different circumstances.

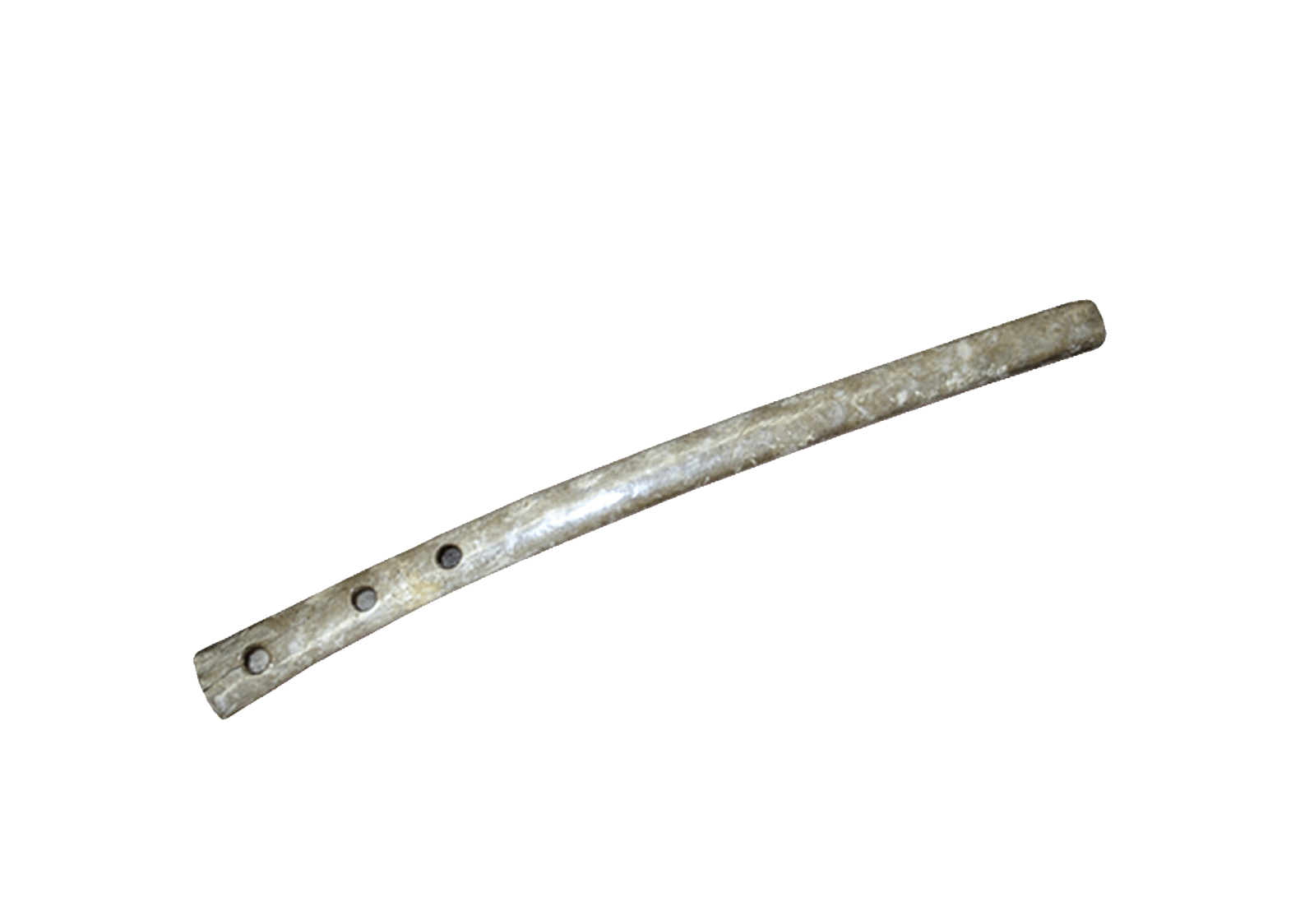

There are still two types of salamuris in Georgia, “tongued” (eniani) and “tongueless” (ueno). The “tongue” is a short reed stopper that is inserted into the salamuri. Tongued and tongueless salamuris differ not only in structure, but also in playing technique and sound. While I was conducting fieldwork, the shepherds living in the mountains of eastern Georgia shared with me some invaluable information: it turns out that in ancient times, tongued salamuris were used for cows, tongueless ones for sheep, and salamuris made out of clay were for pigs.

In fact, shepherds knew very well which animals would better perceive which sound, which meant that, for them, the instrument was not just a means of passing time and enjoying oneself, but actually a working tool. As we can see, Ivane Javakhishvili’s name for this ancient instrument, “a shepherd-boy’s salamuri,” is quite fitting. Its sound evokes amazing emotions. The instrument was played by musician Sandro Nikoladze in 2000. Ethnomusicologists Malkhaz Erkvanidze and Levan Veshapidze participated in this experiment, which was held at the Simon Janashia Georgian National Museum.

The swan-bone, reedless salamuri is kept in the Georgian National Museum, and a copy is in the Museum of Georgian Folk Song and Instruments. In 1987, Shalva Babukhadia made a tongueless salamuri from cattle bones, in accordance with the original measurements.

Cover image: Tongue-less Salamuri

.jpg)