Mravalzhamieri

A Song Wishing for a Long Life and a Sea of Happiness

It is not surprising that Georgians, with their rich tradition of winemaking, also love their feasts, known as supras. The supra, with its gastronomy, wine drinking, tamadas (toastmasters) and toasts, is part of Georgian national culture, attracting the attention of Georgian and foreign researchers and sometimes even becoming the cause of scholarly debates.

In general, folk music sung at the dinner table is characteristic of many cultures. The genre and style of this music is determined by the specifics of the respective culture. In the old days, the repertoire accompanying the Georgian traditional supra consisted mainly of polyphonic table songs and festive hymns, among which mravalzhamieri had a special place.

The word mravalzhamieri refers to both a kind of table song and at the same time a church hymn. The combination of two words—mravali (many) and zhami (time)—is interpreted as: many times, very long. At the end of the divine liturgy, the singes often sing in a church a version of mravalzhamieri from some part of Georgia (audio example).

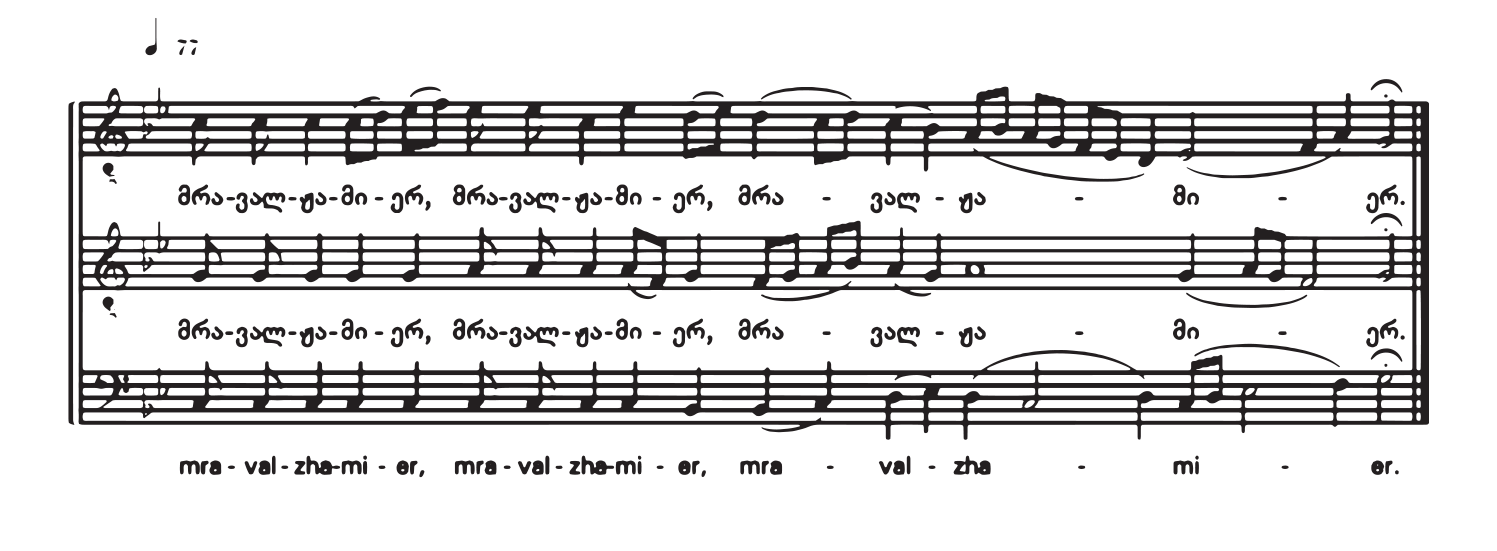

Mravalzhamieri (Gelati school)

The mravalzhamieri is especially characteristic for regions rich in grape varieties and winemaking traditions, such as Kakheti, Kartli, and Meskheti in Eastern Georgia, and Rach’a, Imereti, Samegrelo, Guria, and Ach’ara in Western Georgia. In some places, there are dialect variants of the name: “Brevalo” in Guria; “Zhamiel,” “Zhamielurmi” in Ach’ara.

Some mravalzhamieri names also transmit some history. For example, the “Aslanuri Mravalzhamieri” is named after Aslan Eristavi, who lived in Rach’a in the nineteenth century. It is said that he taught the song to the local choir. “Ekvtime’s Mravalzhamieri” bears the name of the Rach’an singer, Ekvtime Gogoladze, while “Benia’s Mravalzhamieri” is named after the Imeretian choir master Benia Mikadze. The short mravalzhamieri common in Kartli and Kakheti is sometimes referred to as “Erekle’s Mravalzhamieri.” According to oral accounts, this song was especially loved by King Erekle II (1720-1798). Quite frequently, the name indicates the place of origin of the song. Many are named after villages and towns: Telavuri (from Telavi), Shilda (from Shilda), Kutaisuri (from Kutaisi), and others.

Iliaoba, 1895

Most of the mravalzhamieris from western Georgia recall those from the chanting tradition. However, unlike sacred hymns, they are characterized by starting with one voice, and have a freer, sometimes contrasting development of voices. These songs feature a special regional performance manner and variations of the main text: the word “mravalzhamier” can appear as mrevalozhaimero, mralzhaimiero, mravalozhamier, mraivalzhamier, etc. The 1907 recording of the “Guruli Mravalzhamieri” is the first gramophone recording of this genre in West Georgia. The song is performed by Gigo Erkomaishvili (damts’q’ebi, beginning voice), Giorgi Iobishvili (modzakhili, joining voice) and Artem Erkomaishvili (bani, bass).

In eastern Georgia, mravalzhamieris are common in the Kakheti, Kartli and Meskheti regions. Kakheti could be considered the birthplace of table songs, due to the sheer number and variety of examples. In this region, both long and short mravalzhamieris are common. They are characterized by a sustained bass drone as a background for the higher voices, which sometimes alternate and sometimes sing simultaneously. The manner of performance is melismatic, with winding ornaments. In this region, long and short mravalzhamiers are performed. These songs have a particularly emotional quality, both due to changes in tonality—a tendency to gradually rise in pitch—as well as the variety of content in the text. The lyrics address the topics of life and death, enmity and love, homeland and honor.

This 1912 recording of “Mravalzhamieri” from the village of Shilda features famous masters of Kakhetian song: Levan Asabashvili and Batho Rostomashvili, singing the high voices.

Back in the 1820s, the German scholar Eduard Eichwald, who traveled to Georgia, after listening to Georgian singing, wrote in his diary:

“the songs rise from the depths of their souls... they exert all their strength and seem to take the soul out of their bodies in order to have us hear deeply soulful sounds.” (1).

Though Eichwald never met the singers from Shilda, his words are amazingly fitting to their singing.

In its function, the mravalzhamieri is a kind of blessing: a desire to stay for a long time, a plea for well-being. However, over the centuries, the table songs of a people who find themselves often fighting for freedom, have also developed a motif of victory over the enemy: “I will die with the sword at my side, ready to cut off the enemy's head”; “Those who come for us will meet their own swords”; “Let not the enemy rejoice over us, nor make us sad”—these are just some of the texts of various versions of the Kakhetian mravalzhamieri.

Niko Pirosmani, Feast in Kakheti

The mravalzhamieri is so important to Georgians that it has also earned its place in urban folklore. Urban folklore is conventionally divided into two branches, eastern and western. The first, in the cities of eastern Georgia, developed as a result of the influence of Eastern musical cultures from the seventeenth century, while the second appeared in western Georgia in the nineteenth century, as a result of the popularity of European classical music. Urban mravalzhamieris come from cities in Western Georgia. Their harmonies are based on the principles of European classical music, whose influence is also felt in the performance style.

One of the most popular examples among urban mravalzhamieris is the “C-dur Mravalzhamieri,” also known as the “Kutaisuri Mravalzhamieri”. “C- dur” is the German equivalent of C major, from which the name was derived. This song must have been created in the western Georgian city of Kutaisi. According to historical records, it was first performed on stage by Pipinia Mikeladze, famous for her humor and wit, along with his friends, Bondo Mikeladze, Sandro Paghava, Kokinia Dgebuadze, and Daniel Janashvili. The performers of the first recording of the “Kutaisuri Mravalzhamier” in 1909, unfortunately, are unknown. Who knows, maybe the voices on the recording belong to the Mikeladze and his friends!

“In Kutaisi, I saw a feast with Kakhetian wine, in Imeretian style, ”reads a diary entry by the French archaeologist and ethnographer Joseph Berthelot, baron de Baye, who traveled to Georgia at the end of the nineteenth century. He notes,

“every toast is followed by a chorus of those present wishing for long life and great happiness.” (2).

These songs of longing are still sung in different parts of Georgia.

References:

- 1.Eichwald, Eduard. 2005. Sakartvelos shesakheb (On Georgia). Tbilisi: Artanuji. p. 133.

- 2. De Baye, Baron. 2011. Sakartveloshi [In Georgia]. Tbilisi: Artanuji. 41-43.

Cover image: Feast in the Shervashidzes’ garden. "Iveriel" Digital Library of the National Parliamentary Library of Georgia

.jpg)

%20%E1%83%97%E1%83%94%E1%83%9D%E1%83%9C%E1%83%90%20%E1%83%A0%E1%83%A3%E1%83%AE%E1%83%90%E1%83%AB%E1%83%94%20-%20%E1%83%A1%E1%83%90%E1%83%A0%E1%83%94%E1%83%93%E1%83%90%E1%83%A5%E1%83%AA%E1%83%98%E1%83%9D%20%E1%83%A1%E1%83%90%E1%83%91%E1%83%AD%E1%83%9D%E1%83%A1%20%E1%83%AC%E1%83%94%E1%83%95%E1%83%A0%E1%83%98-min.jpg)