Unknown Poem by Mikha Khlashvili

On 20 August 1934, by a resolution of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Georgia (the Bolsheviks), a nationwide celebration marking the 750th anniversary of the birth of Shota Rustaveli was scheduled for October 1937 throughout Georgia. The same resolution announced a number of creative competitions: for the best design of a monument to Shota Rustaveli, for a painting based on his poem, for a musical composition and a film script, as well as for the publication of the poem in an academic edition and its translation and publication in foreign languages. The People’s Commissariat for Education established the Rustaveli Prize to reward the best highly artistic poetic work. In short, Shota Rustaveli and his poem completely captivated the country’s artistic and scholarly circles.

The peasant newspaper of the People’s Commissariat of Agriculture of the Georgian SSR, Kollektivizatsia, responded to this initiative in its own way. Two days later, on 22 August, it announced that it would launch a “Shota Rustaveli Cultural Campaign”[1] and called on literate people from different parts of Georgia to collect poems on new, topical themes by anonymous peasant poets with natural talent, as well as folk-adapted popular excerpts from Shota Rustaveli’s poem, and send them to the editorial office. The best of these were to be printed in the newspaper and later published as a separate book. The newspaper’s editorial board also promised a reward for the most “diligent” participants.

About a week later, the editorial office of the newspaper Kollektivizatsia received a large number of folk poems, collected from peasants and sent from various parts of Georgia, often by the peasant poets themselves. The newspaper’s then-editor, Akakii Chkonia, selected poems for publication at his discretion. As a supporter of communist ideas, he favoured poems on socialist themes, publishing them in a special section on the third page of each issue under the title “Shota’s Cultural Campaign.” A year later, when Akakii Chkonia was transferred to the position of opera director,[2] the newspaper continued for several more months before being closed.

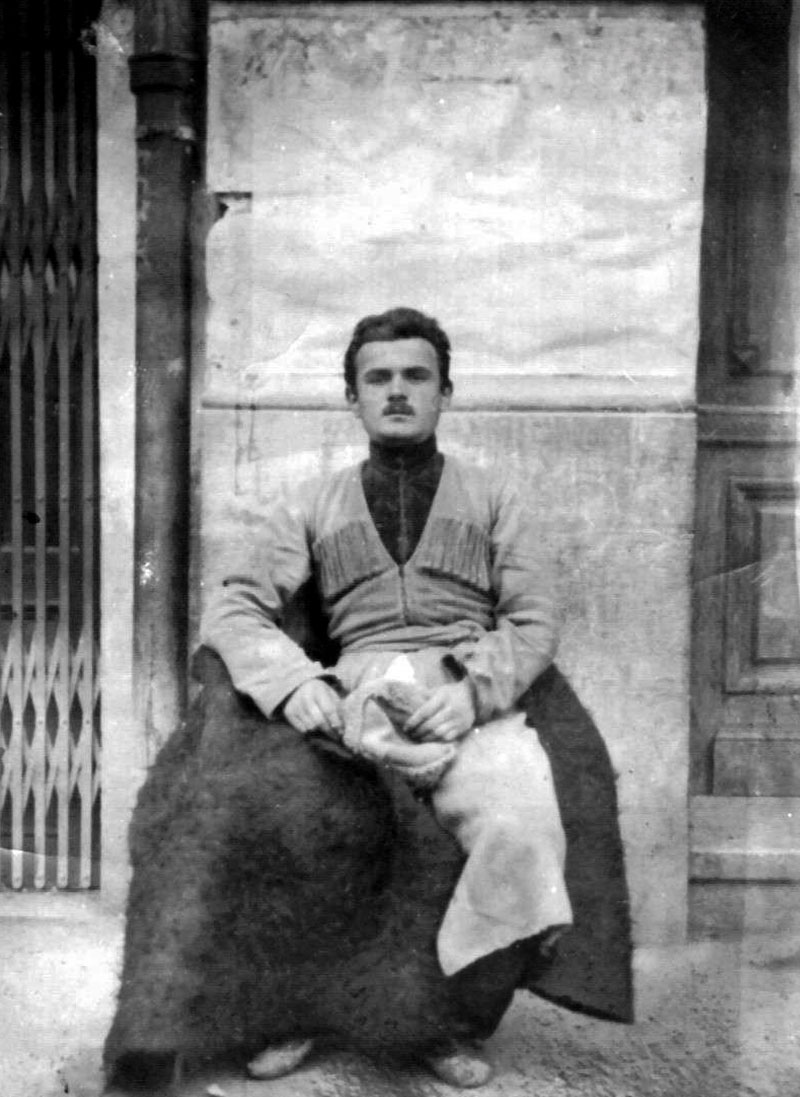

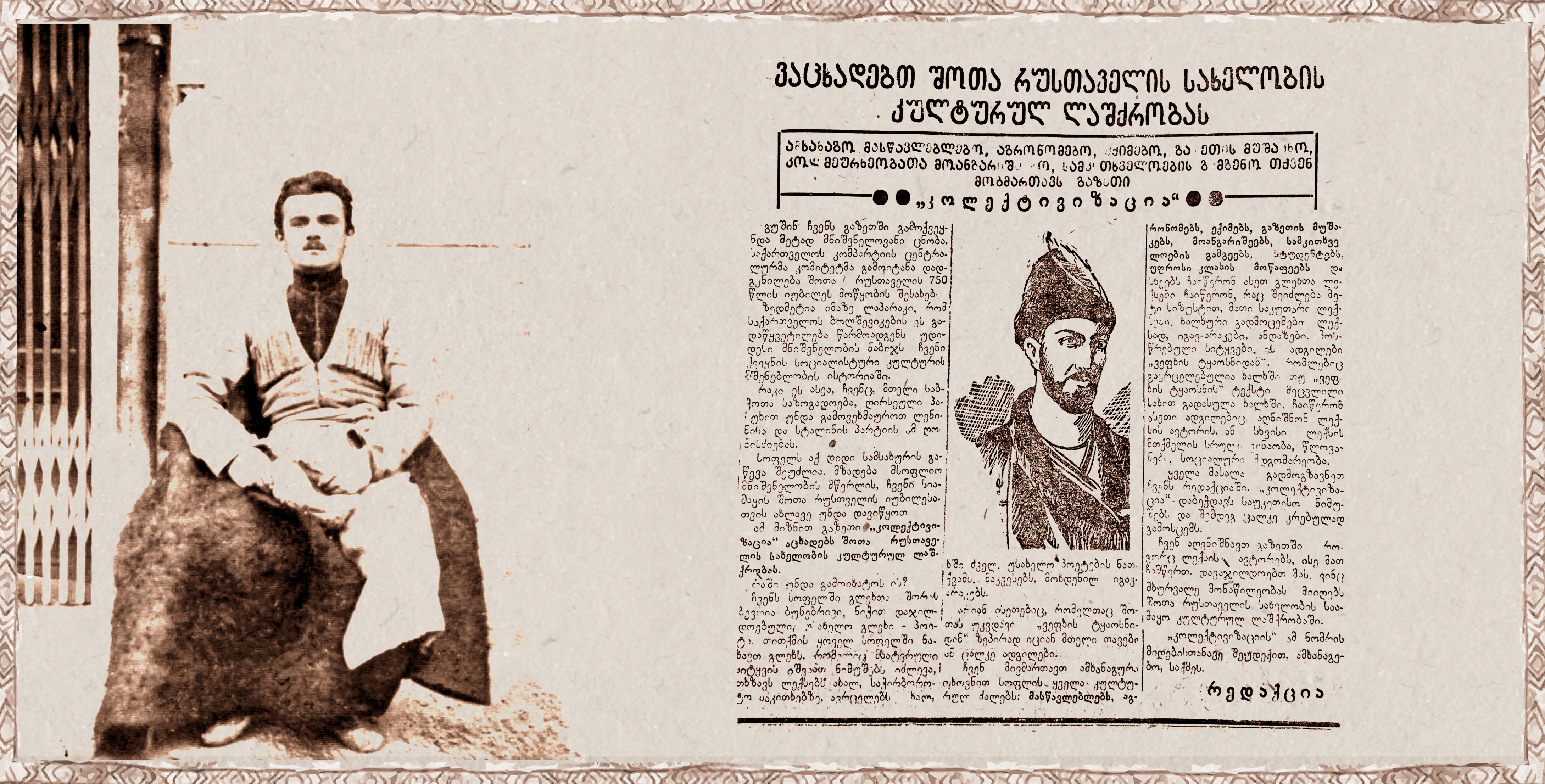

Akaki Chkhonia

In 1935–1936, Akakii Chkonia compiled and published a three-volume collection titled Treasures of Folk Literature, known for containing poems collected during Shota’s Cultural Campaign. These volumes were considered the main source of Soviet folklore until the 1980s and served as the basis for subsequent collections, whose editors selected poems in accordance with political correctness. Finally, Akakii Chkonia transferred the archive he had collected over nearly a year — about 10,000 poems, according to his own account — to the Literary Museum.

Working with the materials of the newspaper Kollektivizatsia at the Literary Museum, it becomes clear that Comrade Chkonia selected the submitted poems according to his own taste and often edited them: he corrected words, rhymes, and sometimes entire phrases. Frequently, entire stanzas in the manuscript were crossed out, parts of stanzas were omitted, and occasionally the title was changed, etc. The editor was especially cautious about publishing ambiguous poems, and for this reason even highly artistic works were often withheld.

Akakii Chkonia was quite an experienced party worker; in his youth, he had been a member of the organisation of young Marxists (Mensheviks), and his caution was also shaped by his own biography. Therefore, the note from Vano Khornaui, sent to the editorial office of the newspaper Kollektivizatsia, in which he stated that this poem had been recorded by him in 1922 from Mikha Khelashvili, would almost certainly never have been allowed to see the light of day.[3]

It is precisely thanks to the “Shota Rustaveli Cultural Campaign” that the poem, sent by Vano Khornaui in 1934 to the archive of the newspaper Kollektivizatsia at the Literary Museum, has survived. Since it was immediately censored, it does not appear in any of Mikha Khelashvili’s published poetry collections. Our readers are encountering this poignant, romantic poem for the first time, in which the lyrical hero longs for the time when he will be able to fully relax with his beloved woman:

May[4] the old times pass, and the new ones begin,

so that I would never feel guilty for being with you always.

With you, I would not move, even if bullets flew at me;

When I saw you, my beautiful, my wounds would heal.

Even if the whole world stood against me on the road ahead,

it could not turn me back, even if many tried.

I wish my grave could be dug in your heart,

and my shoulders and arms would melt upon it.

What harm would it have done if we had lived together?[5]

Mikha Khelashvili

No one will be surprised that neither Akaki Chkonia nor the Georgian folklorists of the later period who worked with this archive dared to publish this poem. Under the conditions of total Soviet censorship, when even mentioning Khelashvili’s name was forbidden, no one could avoid severe repression. Yet it took courage to preserve anti-Soviet poems in the archive without revealing their author. Out of fear or self-preservation, Akaki Chkonia could, with a single sweep of his hand, have destroyed anti-Soviet and counter-revolutionary poems (and it is not excluded that in some cases this may have happened), and we would never have known of their existence; we would not have known of the resistance movement that still persisted among the Georgian people despite being suppressed by the harshest methods, and we would not have understood the popular memory and love for the poet of freedom who was brutally killed.

Georgian folk song “Bindisperia Sopeli,” whose text is based on the poems of Niko Samadashvili (“Bindisperia Sopeli”) and Mikha Khelashvili (“Lekso Amogtkom”).

Performed by the folk ensemble “Bakhtrioni”, based at the Akhmeta Municipal Cultural Center, led by Beka Bidzinashvili. Soloists: Beka Bidzinashvili and Zura Mamukelashvili.

[1] For a detailed discussion of this campaign, see:

Intskirveli, Eteri. 2024. “Shota Rustavelis Sakhelobis Kulturuli Lashkrobis Guruli Masalebi” [Gurian Materials of the Shota Rustaveli Cultural Campaign]. Tselitsdeuli 16 (2024): 111–126.

[2] For details on Akakii Chkonia’s activities at the Opera Theatre, see:

Intskirveli, Eteri. “The Decade of Georgian Art: Behind the Scenes of the Opera House.” Georgian Folklore 7 (2025): 17–29. https://geofolk.ge/en/article/qartuli-khelovnebis-dekada-operis-kuluarebshi/306/

[3] The poet Mikha Khelashvili became widely known to the public in the post-Soviet era, when speaking about him as a participant in the 1924 uprising was no longer prohibited. His poems were circulated in the Soviet Union under the name of folk creativity.

[4] Translation from Georgian by the translator. This is a sense-for-sense translation conveying the meaning, imagery, and tone of the original poem; it does not attempt to reproduce its poetic form or style.

[5] Literary Museum Archive. Kollektivizatsia Newspaper. Fund No. 20029-ხ, p. 17.

.jpg)