“Daddy's Garmoni -Playing Girl” - Lela Tataraidze

“Daddy's Garmoni[1]-Playing Girl” - Lela Tataraidze[2]

The idea of recording an interview with the inimitable author and performer of Tushetian songs and tunes, Lela Tataraidze, came about in celebration of her 75th birthday. Organizing the interview might have been challenging if it weren't for Eter (Etero) Tataraidze—poet, folklorist, and Lela's sister—who was also present during the recording. We believe readers will find his participation and insights particularly engaging.

Lela Tataraidze's jubilee celebration is scheduled to take place on October 24th on the main stage of the Rustaveli Theatre. Additionally, the Folklore Centre's photo project, titled “Lela and Etero,” was also dedicated to this milestone.

I tried to prepare as thoroughly as possible for this interview, but I couldn’t find any previous interviews with you. So perhaps we can call this an exclusive interview, for which I am very grateful.

Yes, you can say that, because I never really talk about anything.

Tell me, how are you living now? What is your daily life like?

Age, health—everything is fleeting. Age brings its own set of

Your 75th birthday is approaching. How do you reflect on your life so far? When you think back, what comes to mind first? Where have you won, and where have you lost?

What can I say about wins and losses? I don’t remember much; I don’t even try to recall what happened, what I created, or what I did. Sometimes I find myself in a completely different state of mind. I never spoke up or made a fuss about what I accomplished or what I couldn’t achieve; What hurt my heart or brought me joy—those are things I keep to myself. I prefer silence over talking. I love thinking, ,,thinking is the mist of mountains…”[3]

Can you recall when you first felt connected to song?

I've been connected to singing since I was a child, but I never thought I would make it a profession or pursue it seriously. I never had that desire. I wanted to follow a very different profession, but they didn’t allow it, and that’s why…

What profession did you want?

I wanted to be a pilot and fly and Mum went mad about it and said no. Dad didn’t say much—neither yes nor no. Mum just said no. I asked, 'Why not? How will I be able to know if you’ll be here or up there?' (pointing to the sky—R.K.) 'What if anything happens?' I also said, 'Don’t people die on earth too?' 'No,' she said, and then she left me with the papers already prepared, just like that.

When did you first sing?

When I finished secondary school, Giorgi (Bukhuti) Darakhvelidze came to Alvani and formed an ensemble. I was the leading soloist there. By the way, this idea also came from Bukhuti. He told me that I should pursue this work and study it. There were several accordion-playing women with Bukhuti. At that time, the Decade of Georgian Art and Literature (held in Moscow in 1958 - R.K.) was taking place. Bukhuti came to the Akhmeta district to form an ensemble right away. He was a very talented person, a gifted choreographer. He believed that folklore should be at the forefront. He gathered 65 women with accordions, and we danced while playing. The dance was designed in such a way that the 65 women with accordions formed the number 50 on stage. We performed in the hall of the Palace of Congresses in Moscow. The performers wore three colors, and I was the only one in white, as the leading soloist of the ensemble.

Was it your debut on the big stage?

It was my first trip outside the country. Before that, at the district Olympiads, I used to play the accordion and sing all the time at school.

If you go back to your childhood, what do you remember most often?

What other entertainments did we have in Alvani, especially in Tusheti? We children would gather to stage festive plays, dances, and stories. We would portray a wolf, a lamb, and other characters using decorations. We all sang at home, and the sounds of music always filled the air.

Lela's sister, Etero Tataraidze, joins the conversation:

I’ll join in, please. They wouldn’t let me sing. As soon as I started singing with them, my three siblings would immediately freeze. My mother would ask, ‘Why won’t you let her sing?’ And all three of them would shout at the same time, ‘She’s messing up!’

Did the accordion come into your life after you travelled to Russia?

No, it was before that. The accordion was always with me at school. At the Olympiads, school events, and district events – I was always the one with the accordion. At first, I didn’t have an accordion, so in Tusheti, I would make a hole in a thin piece of slate, draw a keyboard with charcoal, tie a string to it, and pretend to play the accordion, ‘playing’ the melody with my voice.

Etero rejoins the conversation:

This slate, of course, would cut the rope; the rope is the traditional Tushetian weaving thread. My mother says that her legs were always bruised and cut. The thread would break suddenly, and the slate would fall on her, but she didn't mind. When we were building the house, since there were no windows, only large holes, Lela would sit there, put her legs through the hole, and hold the slate like a 'garmoni.' She sang from morning till evening, so much so that she forgot to eat, and sang for everyone who passed by. When they asked her who she would like to become, she would answer, ‘My daddy's accordion-playing girl.’

How well did you do in other subjects at school?

Technical subjects were far from me; I was more into the humanities – Georgian, history. The teachers loved me for playing the accordion, and they would give me good marks.

What was your childhood song? Which song did you hum most often?

For example, we would hear from my father and uncles, "One shepherd in Shiraki had a bad dream, he got up and told his uncle..." (Singing).

Etero continues speaking:

She had such a voice. When the village would quiet down at night, the wind would carry Lela's singing; it was an incredible voice.

What was your relationship with your parents like when you were a child?

When we were children, and even later in our youth, we had great respect and reverence for our parents in everything. We wouldn't oppose them much. I want this or I don't want this – we wouldn’t dare or even think about doing that. We grew up with a different mentality, especially as mountain people. My father was more lenient. In our youth, how could you become an artist? A stage artist – that wasn’t possible, especially in the village. I don’t remember my father ever saying I shouldn’t pursue this profession. We had concerts, and I would come home late at night or early in the morning. I don't remember my father ever saying, "Where have you been all this time?" My mother wouldn’t say much, but she would stay up all night, especially when I had my car. My mother never slept until I came home, even if it was early morning. When I would come, she would calm down.

You worked as a teacher at Alvani school and kindergarten, as well as the leader of the choir. As a choirmaster and teacher, what was your approach to children and teaching?

I defended my school diploma at Ozhio School in the Akhmeta district. I worked at that school for a year, teaching classes and leading the choir, among other things.At that time, I was young and didn’t pay much attention to it, but over the years, I would meet my former students or teachers, many of whom I didn’t know, but they would greet me warmly, saying, “Teacher Lela!” I realised that I had left love behind there. When I entered the classroom and the bell rang, no matter where the students were, none of them would be outside; they would be waiting for me inside the classroom. Our teachers were surprised because they couldn’t manage the students, who, in the teachers' words, were often disruptive—breaking into classrooms halfway through lessons or making noise. They would ask me, “How do you manage it?” I don’t know—I probably had a completely different approach. I would talk to them about the songs, the traditions, and spark their interest, not just teach them the songs.

Children are one thing, but it’s another matter when you have to work with adults and lead an ensemble or a choir. In your opinion, what challenges and difficulties are related to leading an ensemble?

Trio, quartets, ensembles... I don’t know, it’s difficult. I just can't accept lateness. If someone is an hour late and comes in as if nothing happened, while so many people are waiting, I don’t know what that is for me. With the accordion, I usually move with ‘mekhi’.[4] I was the first one to introduce this technique. I don’t have anything fixed in a frame; whether it's singing or an instrument, depending on my mood, sometimes I’ll make a 2-beat rhythm into a 8-beat or vice versa.

Since 1992, you have worked at the Merab Kostava National Theatre, where you were both a musical arranger and an actress. This was a new field for you. Tell us about this chapter in your life—how interesting was it for you, both as an actress and as a musical arranger, in this aspect of theatre?

I had the same experience in theatre, in cinema, everywhere - in the films of Goderdzi Chokheli, Yuri Kvachadze. In both films I also acted in episodes. I have done the soundtrack for many films. For ‘The Fortress of Surami’ I recorded Zurab's mother's lament (ზურაბის დედის ტირილი) Parajanov and Dodo Abashidze were in the film at the time.

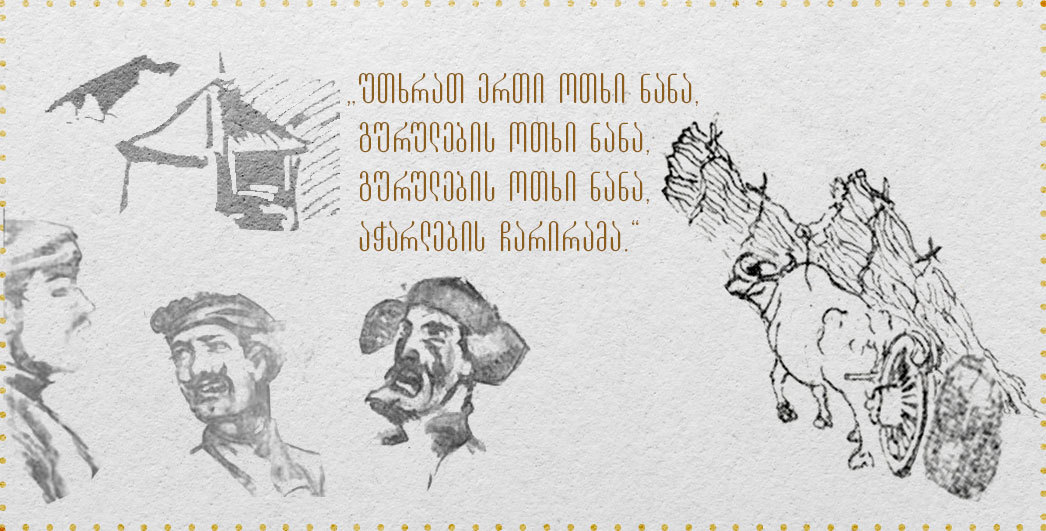

I acted in the play May Your Nest Stay Intact, Eagle, which was about the life of the Tush people, at the Kostava National Theatre. Ninua, the theatre director, would ask me for a year to come and perform with them. There's not much to say about films; what do I have there that’s so special? Nothing. In the films Sorrow of People („ადამიანთა სევდა“), Six Snowy Days („ექვსი თოვლიანი დღე“,), and The Book of the Oath („წიგნი ფიცისა“) — my songs are used. When they made The Book of the Oath, Bidzina (composer Bidzina Kvernadze – K.) wrote the song, and Giga Lortkipanidze was the director. They told me that I should sing the 'Nana' of the Ingiloian woman there. I said I would sing it, but in my style, with melismas and ornamentation, depending on the mood. Then they told me they needed the 'Dalai' – the Tushetian version of the 'zari' (a form of lament). I said that this was a lament sung by men, and it had its own inseparable melody. I performed it there, they liked it very much, and they told me I should perform it too. I refused because women didn’t sing the 'zari.' They brought in Hamlet Gonashvili. Hamlet used to call me 'sister of the song,' never by my name. He was an amazing person, a lover of nature and mountains. He learned it, but his voice didn’t match the song; he himself thought so too. Then they brought in Temur Kevkhishvili and recorded him.

When choosing a text for music, what is your criterion? What do you usually base your choice of poem on?

I don’t choose a poem for music; the poem chooses the tune for me. Even if someone asks me to make a song from their poem, it’s not my world. I’ve never done anything by order in my life. When I read a poem, if even two lines stay in my heart and I like them, the poem itself begins to bother me, and when it comes, it comes… It might even force me to get up at night from my bed. When I read the poem You, Lion, Killed by the Lion, it came to me by itself, just like the others.

Your and your sister’s stars of fame rose together. There is also Etero’s poetry in your work. You share a common history, having experienced the same stories, feeling joy and pain in the same way. When you choose your sister’s poem, do you sometimes see the emotions of your childhood in her words? Do you connect it to shared memories?

What is mine, is hers... The tears are the same, the joy, the pain, everything. It evokes emotions in me that might be hard to perceive and absorb in the same way from others. Sometimes, I get the feeling that neither the author of the poem nor I am the creator of the song, it is all Tusheti, with its own beauty, struggles, emotions, joys, and everything that our ancestors had and were. In the past, when we used to travel in Tusheti in trucks, our whole family would sit on the luggage. The boys had amplifiers, and my songs were playing... Even then, I thought that it wasn't me, that I wasn’t singing. It’s a completely different world there, in Tusheti.

Etero joins in again:

We were at Dano’s (Etero and Lela’s village in Tusheti – K.) hill on the last evening. We were sitting, and sometimes I would read a poem, and sometimes you would sing. The women said, 'Oh no, don’t you pity Tusheti? When you leave tomorrow, no one will hear your poem, and no one will hear your song!' – This phrase affects me deeply, because that time will come when we leave forever (tears welled up in her eyes as she spoke).

What about the childhood resentment? What did Etero do to upset you in childhood?

Etero would often run after our mum whenever she went out for work. Then Mum would turn around and call, ‘Lela!’ — meaning I had to bring Etero back home. Of course, she would obey me and come back right away. Apart from singing and love, we had nothing at home. By the way, both my mother and father sang, but they couldn't express themselves (on the stage) because of the life back then. Being a musician was considered shameful, men's singing was frowned upon, and they would sing secretly.

What advice would you give to young people?

Love your homeland, Georgian culture, and history... Think about the future and be the kind of people who are loved by everyone, by their nation and homeland.

If it weren't for singing, what would you be doing?

If it weren’t for singing, I would be a pilot.

[1] The term 'გარმონი' in Georgian refers to a traditional accordion, often a diatonic button accordion, which plays a significant role in Georgian folk music. While 'accordion' is used as the general translation, it's important to note that the specific type of accordion mentioned may differ from the more commonly recognized piano accordion.(ed.)

[2] The interview was recorded prior to the jubilee celebration of Lela Tataraidze, which took place on October 24 at the Rustaveli Theatre.

[3] Lela Tataraidze's phrase "Thinking is the mist of mountains..." is a rephrasing of Vazha Pshavela's original line, "Mist is the thinking of mountains," employing a rhetorical device known as chiasmus. This inversion enhances the poetic effect and offers a fresh interpretation of the original metaphor. (ed.)

[4] As Lela explains, "The mekhi [known as the bellow in English] is a part of the accordion, through which I developed a playing technique involving small, sharp movements and ornaments. This technique adds a dynamic and expressive layer to performances, enabling quick shifts and surprises in the music, enhancing its overall texture and emotional impact."

.jpg)