COLONIALISM AND CHANGE IN SCOTTISH BAGPIPING BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT

Background and Context

The concept of ‘Bagpipes’ is suggested to have existed as far back as 1300 BC as evidenced from early sculptures, and later references by the Greek writer Aristophanes in the 5th to 4th century BC. Further evidence appears in terracotta figurines from Alexandria in Egypt in the first century BC, which have instruments with what appears to be drone accompaniment to a chanter or chanters. The first mention we have of what is believed to be mouth-blown bagpipes in Latin, is with a reference to tibia utricularis ie. bag-blown double-pipes [1] with a bag of skin, dating to the period of Nero, the emperor of Rome in the first century AD. [2] [3] That the pipes were an important and popular component of the musical cultures of ancient Greece and Rome is without doubt. [4] Players were often publicly funded, and there were both male and female players – the numbers of whom who played the pipes being about equal. According to the music scholar Francis Collinson (1898-1984), to establish a link between the Roman double pipes with those in the Scotland is impossible. [5] However, the early existence of pipes of some kind, which has given rise to a large repertoire of pipe music of different genres, as well as different forms of pipes, cannot be ignored by history. The double-pipes were already in England before the Romans arrived in the first century AD but there is seemingly no evidence that the Romans brought them. [6] At the present day, most of the countries of Europe have some form of bagpipe with France alone having about 15 different types of bagpipe played there.

Ireland and Scotland

The bagpipes are likely to have come to Scotland from Europe and were adopted in the Gaelic societies of Ireland and Scotland at least by the early 16th century.

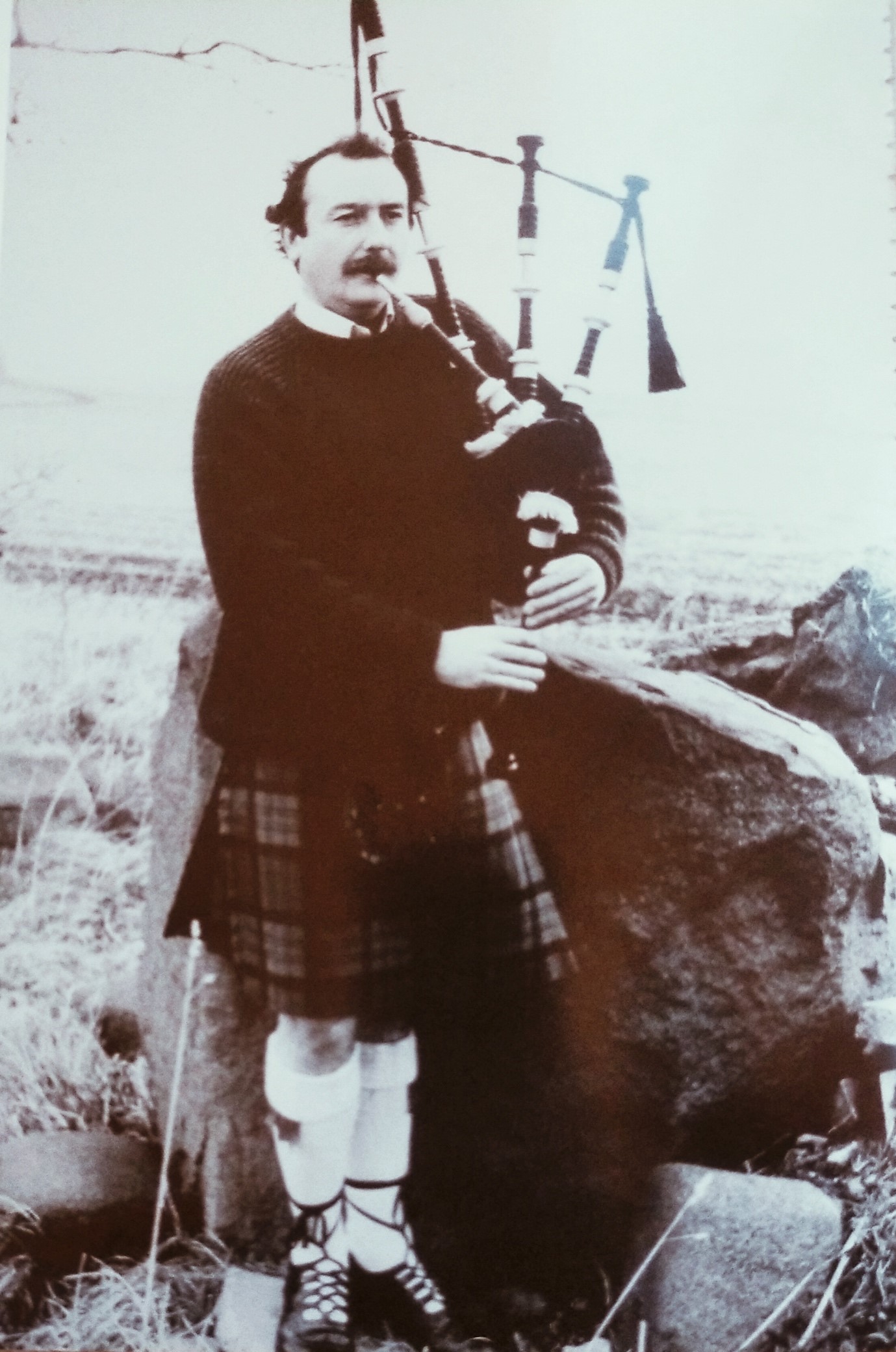

In the photo: the Highland pipes are being played with the bass drone closest to the body and the two tenors on the outside.

The role of the bagpipes several centuries later, in the court of Gaelic society, is historically well recognised both in Gaelic speaking Ireland and Scotland.

Whichever form preceeded it, the Highland bagpipe was eventually standardised as an instrument with a chanter, blow-stick, two tenors and one large bass drone. The military used this three-drone format and that became the standard structure in both Scotland and Ireland.

In Ireland, the bagpipes were called the ‘War Pipes’ and in Scotland, following the failure of the 1745 Jacobite rising they were similarly deemed to be ‘an instrument of war’. In both Ireland and Scotland, with their shared Gaelic tradition they were called pìob mhór. Our earliest references to bagpipes (rather than to mouth-blown pipes without a bag) in Scotland are very sparse and they are rarely mentioned, even in Gaelic sources, before the late 16th century. An mid 16th century one, in a martial context, is from a Frenchman’s observation of the Scottish Highland soldiers at the Battle of Pinkie near Edinburgh in 1547 stating:

“while the French prepared for combat, the wild Scots incited themselves to arms by the sound of the bagpipes” [7]

This may suggest that the bagpipes were forever associated with martial music and with acts of war. [8] The bagpipes were patronised by the clan chiefs throughout the 17th century especially and reached their zenith within the Gaelic court in ceòl mór - literally ‘big music’, with its themes and variations. Today this is misguidedly called ‘classical music’ - Pìobaireachd (borrowed into English as pibroch), for a Gaelic speaker, simply means ‘the art of piping’.

In the earliest publication of bagpipe music scores in 1820 the title identifies the contents as ‘The Ancient Martial Music of Caledonia called Piobaireachd’. [9] However, an earlier analysis of this music in 1760 in manuscript form and later published in 1803, does not mention the word Pìobaireachd nor Ceòl Mór but rather Martial Music. [10] Gaelic speakers, though, use a simple term of convenience, Ceòl Mór. This term incorporates a whole range of different rhythms and tempos of tunes with variations. For example, there are Laments (bardic and keening), Gathering and Warning tunes, Marches, Salutes and a wide range of different rhythms implied by the titles and internal evidence of the repertoire. Ceòl Beag - literally ‘small music’, in contrast, encompasses a repertoire with much wider differences between them: Marches, Strathspeys, Reels, Jigs, Hornpipes and Airs. Ceòl Beag is also played in very measured time for dancing - apart from the rubato Slow Airs.

The point I am making is that the blanket use of the terms piobaireachd or pibroch to describe a range of different characteristics of melodies in this ‘classical’ genre has, I believe, had a subtle influence on the performance style of this martial and court music. This blanket use of one word to include all the genres and differences between them has led to a levelling out, as it were, of the rich repertoire into a single homogenous performance style that ignores the music’s functions in the Gaelic society from which it arose. This signifies the beginning of a departure from the cultural context of Gaelic society to an English colonised one. Although the editor and compiler of the first published collection of Ceòl Mór (1820) was a native of Skye and a Gaelic speaker, called Donald MacDonald [11], the English texts were written by a chosen individual who was not a Gaelic speaker and would probably have formulated the title. The music was published for the upper echelons of society, being relatively expensive, and had elements of post-Jacobite romance enshrined within its pages and piano accompaniment.

If we go back to the early 17th century, we find that the Statues of Iona, passed in 1609, required the heirs of the Gaelic Highland clan chiefs to be educated in English-speaking Protestant Lowland schools. This was a major step in the process of colonisation and imperialism. At the beginning of the century, chiefs of clans were being awarded with honours by the English and Scots governments in the form of titles such as that bestowed to Sir Rory Mór MacLeod of Dunvegan in 1613. By the end of the century, patronage by chiefs for their musicians, poets and entertainers was being abandoned. In 1693 the hospitable chief of the MacLeods of Dunvegan Castle in Skye, who had patronised the blind harper and poet Ruairidh Morison, died, and his son, having been educated in a Lowland school, abandoned the tradition. [12] A powerful song was written by Ruairidh, Òran Mór MhicLeòid [The big song of MacLeod] which berated the abandonment of patronage in the castles of the Gaelic chiefs. As the harp lost its patronage, the martial music of the pipes became increasingly dominant.

The 18th century witnessed the decline and destruction of Gaelic society through the Jacobite battles of 1715 and the final massacre at Culloden in 1746. Gaelic society was never to recover from this nadir.

The Battle of Culloden resulted in the banning of the highland dress, including the kilt, by the English Hanoverian government. [13] Bagpipes were not banned [14] as many presume, but the whole culture was subject to severe repression through burning houses, killing livestock, crops and evicting people. However, in the intervening period men were being press-ganged and captured all over the country up until 1756 when the big push started to recruit Highland soldiers for the British imperialist expansions in Europe and the East Indies. In the seventy years following Culloden military recruitment emerged as the single most successful British government policy implemented in the Highlands.[15]

Throughout the 18th and the early 19th Centuries the bagpipes came to be recognised as a ‘martial instrument’ or an instrument of war inciting people to battle, after it had been part of the retinue of the clan chiefs in the Gaelic court with the older harp, for centuries. It did so to such an extent that in Donald MacDonald’s 1820 publication, it is declared that the “The Bag-Pipe is, perhaps the only national instrument in Europe. Every other is peculiar to many countries, but the Bag-Pipe to Scotland alone.” - such was the image perceived within Scotland but probably not from without; because it is not correct. However, the tenor of these comments is one of a particular romanticism of martial heroism and national pride as part of a much bigger imperialist picture. Many people have claimed that the Highlanders were banned from playing the pipes, post-Culloden, but this was not the case. They were certainly not encouraged and “almost completely laid aside.” However, it did not take the English government long to realise that the most efficient way of getting Highlanders to fight in Imperialist battles of the British around the world was to raise and recruit Highland regiments that by tradition would have pipers accompanying them on the battlefield. The pipers, clad in tartan [16], formed the indelible image of the brave Highland warrior-soldier being led into the field of battle by the unarmed piper playing a rousing tune to incite them to inexorable bravery. These realities continued up to and including the second world war.

Initially, the music used for daily standing orders in the regiments, from reveille to lights off in the evening, were tunes from the ceòl mór or pibroch tradition – tunes that were well entrenched in Gaelic culture. In an early regiment, between 1778 and 1783 [17], a gathering tune was Cogadh neo Sìth [War or Peace]; A' Ghlas Mheur [The Finger lock] was used as a reveille; Bodaich nam Briogais [The Old Men with the Trousers] was used for ‘trooping’ - more like what became the ‘marches’ more commonly identified in the ceòl beag or light-music genre, rather than the ceòl mór. Some of those ‘classical’ pieces were taken from common-or-garden melodies already well known in Gaelic oral tradition. The name ‘marches’ used in the ceòl mór genre was a translation of the Gaelic word spaidsearachd - the meaning in Gaelic is closer to strutting around than to marching in regular measured time.

Here are some audio examples of some well-known orally transmitted melodies from Gaelic tradition, initially used for different orders of the day in the regiment. First are audio examples of the themes or urlars of these tunes as they would have been played at the time of their use. I will follow this with audio examples of the same pieces as they have become standardised in competitions and rigidly adhered to at the present day:

Cogadh neo Sìth (War or Peace)

A’ Ghlas Mheur (Fingerlock)

Bodaich nam Briogais (The Old Men with the Trousers)

However, these tunes are now played inordinately slowly and clearly not in the style of an incitement to gather or for a wake-up call. Over time, the whole repertoire changed in tempo from a more animated style to a much slower one throughout the 19th century. The reason was that the music was placed into a competitive environment, divorced from natural context, standardised and judged over the period of 200 years to give us a completely different style of performance:

Cogadh neo Sìth (War or Peace) Modern style

A’Ghlas Mheur (The Fingerlock) Modern style

Bodaich nam Briogais (The Old Men with the Trousers) Modern style

The slower versions above have now become accepted as the traditional way of playing these tunes, and incorrectly imagined to be how the great piping dynasties of the 17th and 18th centuries would have played them up until the time of the Battle of Culloden in 1746.

In the ceòl beag repertoire, there was an explosion in the compositions of martial pieces of music e. g. especially Quicksteps and Marches, but also Strathspeys, Reels and Jigs. Many of these had military titles, referring to the regiment they belonged to and/or the particular historic events of the day e. g. 74th's Farewell to Edinburgh; The 72nd Punjabis, The 1st Royal Scots in Macedonia etc – at least 150 of those kinds of titles exist. In the Strathspey genre, many titles were changed from Gaelic into English and named after important people from the landed or military gentry. Thoir an Gille dh’fhear-eigin [Give the boy to someone] was renamed Miss Louisa Campbell’s Delight (after a Campbell landowner’s daughter), later becoming what it is known today as Lady Loudon.

This was a common feature of Highland music throughout the 19th century – not just in bagpiping alone. It would appear to have become more frequent when, in the 19th century, the new landlords who had by now become, for the most part, anglicised, had resorted to the old tradition of supporting a piper to play in their large manor or castle and do the duties expected of them – playing at certain times of day and for guests. How these name changes happened is hard to ascertain, but the pipers have to take some responsibility. Many of the tunes have numerous titles in Gaelic as well as in English or Scots. Not being able to speak the language and being in the service of the patron, it would not be difficult to imagine that a piper might dedicate a tune from their own tradition to their patron. In the present day, Gaelic-speaking pipers have forgotten the Gaelic titles for the most part and that connection is also lost.

Returning to the Ceòl Mór tradition - this was the repertoire that it was considered necessary to acquire before becoming a ‘master’ of the pipes. It had the term ‘classical’ bestowed on it by way of patronage from ‘professional people’ in such a way that every embellishment, over and above the notated score, has been edited and ‘improved’ by an overseeing Piobaireachd Society, and had to be played exactly as notated. In the last forty years or so though, scholarship has been more thorough and less romantic regarding the history of this instrument and its role in Scottish society.

This ‘classical’ music, as it is now commonly labelled, resulted in it being performed for the public through competitions that were started in 1781 by an organisation, The Highland Society of London, that set out to standardise the music and to “accommodate its Music to all other instruments – such as the Organ, Piano-Forte, Violin and German Flute.” [18]

It is now an ‘Art Music’ rather than the functional music of communities and a people. It was patronised and slowly changed by those people whom the French writer Stendhal called:

“men of letters who consider the privilege of criticising arts and music as a legitimate appendage for their professional titles.”

The performance style has changed so much from the free expression and appropriateness that emanates from function. As the new style has been ingrained into the piping culture for some time now and the competitions have been the main platform, with limited communication with the public, there is a reluctance to change; conformity being the accepted norm. The inferiority complex that has been engendered into the population from years of colonisation means that one can only hope that the next generation will tire of this rigid standardisation.

[1] Double-pipes meaning two chanters. Roman pipers had, like the Greeks, the tibiae impares (double pipes of unequal length with Greek equivalent of auloi Elymoi); and the equal-length tibiae sarranae (Greek equivalent diaulos).

[2] Collinson, Francis. 1966. The Traditional and National Music of Scotland. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul p. 95.

[3] Ibid., 30, 42–43, stating that Nero was a performer of the bagpipes.

[4] Ibid., 37-38

[5] Ibid., 57

[6] Ibid.

[7] Cannon, Roderick D. 1988. The Highland Bagpipe and Its Music. Edinburgh: John Donald. p. 8. The original source here is De Beaugué, Ian [Jean]. 1556. Histoire de la Guerre d'Ecosse. Paris: Ian De Beaugué, p. 54.

[8] Interestingly, extracts from Ancient Greek texts referring to use of the aulos (pipes) in battle by the Spartans used the music of pipes rather than horns or trumpets in battle. The use of pipes is in contrast with the ‘War Pipes’ of Ireland and Scotland in that they were not used for the purpose of making the warriors more aggressive but that they created an image of fearlessness and order that was more effective than the breaking of ranks and disorder often created by incitement to battle in a fierce impetuous manner.

[9] MacDonald, Donald. 1822. A Collection of the Ancient Martial Music of Caledonia, Called Piobaireachd. 3rd ed., improved. Edinburgh: Alex. Robertson.

[10] MacDonald, Joseph. 1803. A Complete Theory of the Scots Highland Bagpipe. Edinburgh: Patrick MacDonald.

[11] He also had, for the first time ever, a number of fully notated tunes from the Ceòl Beag repertoire as a sample of what he was to publish later in 1828.

[12] The last chief to have a harper and fiddler in his retinue was a MacLean, until 1828.

[13] Kilt - A Scottish men's knee-length skirt, made from pleated tartan (a patterned woolen cloth), now mostly only worn for formal occasions. This was developed in the early 18th century from the fèileadh beag or belted plaid.

[14] As Donald MacDonald states in the preface to A Collection of the Ancient Martial Music of Caledonia, Called Piobaireachd (Edinburgh: Alex. Robertson, 1820), “the Bag-Pipe was, for a long time, almost completely laid aside.”

[15] MacKillop, Andrew. 2000. ‘More Fruitful than the Soil’: Army, Empire, and the Scottish Highlands, 1715 –1815. East Linton: Tuckwell Press.

[16] Tartan - The fabric pattern (distinct checkered design) used to make kilts and other clothing. Many specific patterns used are linked to particular Scottish clans.

[17] The Argyle or Western Fencible Regiment, which lasted only five years.

[18] Introduction to MacDonald, Donald. 1820. A Collection of the Ancient Martial Music of Caledonia, called Piobaireachd. Edinburgh: Donald MacDonald.