Interview with Ted Levin

Ted Levin is a notable figure in the field of ethnomusicology, though he prefers to be considered an "ethnographer of music" over traditional labels. Despite his modest self-description as a perpetual student, Ted’s musical journey is remarkable.

Starting with classical piano and academic pursuits in historical musicology, Ted’s path took a turn when his fascination with folk music ignited during his teenage years. Venturing beyond traditional studies, he embarked on a global exploration of music.

Ted’s curiosity led him through American folk music, Celtic lands, the rhythms of India, the melodies of Siberia, vibrant musical traditions of Central Asia, and the rich musical heritage of Georgia. Along the way, he mastered instruments like the banjo and fiddle, transcending cultural boundaries in his pursuit of musical understanding.

Currently, Ted is immersed in writing a book aimed at a nonspecialist readership that delves into the music of the regions he has researched, including Georgia. His work aims to capture the essence of these diverse musical traditions and their impact on global culture.

His reluctance to claim expertise reflects his dedication to continuous learning, making him a guiding light for those who embrace music’s diverse forms.

In this interview, Ted gives us a peek into his adventurous musical journey, sharing his thoughts and experiences as a musical explorer. Through his words, readers will discover the richness of cultural exchange and the endless possibilities that music offers.

Nana Mzhavanadze: You began your musicological research with American music, focusing primarily on Appalachian music, as you mentioned earlier to me. Did this primarily involve studying American “roots” music?

Ted Levin: Yes, in the broadest sense. A lot of current research focuses on the major contribution of African Americans to Appalachian music, which is very much a mix of different influences. Early blues and music descended from Africa as well as Black banjo, fiddle, and guitar players have been central to the sound of Appalachian music. A throughline in all of my musical interests is the notion of the sacred in music and how music expresses the sacred. This fascination began during my time as a young person in Appalachia, where one of my favorite activities was attending church services. I’m not religious myself but I’ve spent a lot of time in religious ceremonies because I think that this context creates and brings out something very strong in music.

NM: Your expertise in Eastern music spans decades, evident in your authored books which, upon discovery online, immediately piqued my interest, which I hope to explore soon. Did your journey begin with an interest in Sufism, leading you to explore the music of Turkey?

TL: Yes, it was my interest in the Mevlevi “whirling” dervishes and their wonderful music, very deep spiritual music, that led me first to Turkey, and I later became interested more broadly in the music of the East, and particularly of the Muslim East. But not only, because later I got interested in Tuva; there aren't Muslims there, they're basically shamanists, animists.

Ted Levin with Bukharan Jewish musician Tohfakhon Pinkhasova, Bukhara, 1990.

NM: How did you first encounter Georgian music, and what sparked your interest? I believe Georgian readers will find your story intriguing.

TL: Learning about Georgia and its music was challenging during my university years in the early 1970s. However, my study of Russian, which began in high school and continued into university, opened doors for exploration. After graduating at twenty-two, I received a fellowship allowing me to travel abroad for a year. I devised a project to journey overland from Ireland to India to delve into traditional music. Georgia caught my attention due to a friend's recommendation of its unique culture and music. In 1974, I embarked on this trip, driving through the Soviet Union to Tbilisi as a tourist. Despite restrictions, I sought local music and attended a concert in Mtskheta at the Jvari Monastery, recommended by Intourist, the Soviet tourist company. And indeed, there was a concert of Georgian music. They never told me the name of the group, though I think it may well have been the Rustavi Choir. They were men in chokhas and singing very, very beautifully. And even though that was a small exposure, it left a huge impression. And after I heard that, all I wanted was to hear more of it.

NM: Had you heard about Georgian music before you came to Georgia?”

TL: No, I had heard about Georgia—about the culture, but not specifically the music. Little information was available. I’m sure if I'd looked harder, I would have found some, but at the time, I was focused on planning my fellowship and explaining to the sponsors why I wanted to go to Georgia. I emphasized its unique culture, language, music, and cuisine. Interestingly, they never asked me specifically about the music.

NM: You said that you studied Russian in university. How did it help with your pursuits?

TL: The first book I read in Russian was Lermontov’s Geroi nashego vremeni—“A Hero of Our Time—and that also piqued my interest in the Caucasus. Lermontov’s descriptions of the peoples of the Caucasus were of course orientalizing, but nonetheless very interesting to me. The other thing that drew my curiosity to the Caucasus was that in university I had become interested in the work of G.I. Gurdjieff. I read his book Meetings with Remarkable Men, and I also read Pyotr Ouspensky’s In Search of the Miraculous. So, actually, thinking back on it, this was one of the major reasons that I wanted to come here.

NM: Lermontov, on the one hand, and Gurdjieff. So, at least once, Russian was helpful, useful [laughing].

TL: Yes, well, Russian was indeed useful. When I arrived here in 1974, everyone spoke Russian. They spoke Georgian, but they also spoke Russian. So I had no problem. My Russian was not very good, but it was enough to fumble around in the language and feel the power of connecting to people who were living, as we called it then, behind the Iron Curtain. That was the term that was used. And this was a novelty for me. It was very exciting to talk to people my own age who had grown up in this utterly different system, utterly different world, and to find out that we had common interests, that we were very much alike. I felt a deep connection to people here when I first came. Gurdjieff’s books had sparked my interest in the idea that there was some kind of esoteric knowledge that could be discovered and that had survived from the ancient past in monasteries and remote places. Of course, as a charge of the Intourist company, camping out in their campgrounds or staying in their motels, going to monasteries and seeking ancient knowledge was unthinkable. Nonetheless, Gurdjieff’s ideas whet my appetite for this kind of exploration.

NM: Before we return to discussing Georgian music, I recall from your recent presentation that you mentioned not being an expert in Georgian music. However, you have written about and studied other forms of music, such as Central Asian music. Could you please elaborate on your scholarly interests in other musical traditions and the contributions you’ve made in those areas?

TL: It was my interest in music within the world of Islam that drew me towards Central Asia, along with my fascination with Gurdjieff’s experiences in Bukhara, where he encountered Sufis and their spiritual practices, including Sufi dances. While I wasn’t trained as an ethnomusicologist, my background is in musicology. In Uzbekistan, I became immersed in the classical music patronized by the emirs of Bukhara, known as shashmaqam, consisting of six maqams (modally-organized suites). This extensive repertoire comprises art songs and instrumental music organized into six large suites, each containing numerous pieces. The texts were of Sufi origin, although they were replaced during Soviet times. Anyway, no one in the West—from what the Soviets called kapitalisticheskie strany (capitalist countries)—had really studied this music. So, I was the first.

NM: Because of the Iron Curtain?

TL: Yes, the Iron Curtain. In the late 1970s, I spent a year in Tashkent—1977–78. At that time, scholars could only travel between the USA and the USSR through official exchange programs operated by the USSR Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the US State Department. The total number of exchangees per year in the humanities and social sciences was only twenty-three for both countries, across all subjects and cities. So I was lucky to get one of the twenty-three places. Most Americans went to Moscow or Leningrad, and I was only the third or fourth American to have gone to Tashkent to study. The others had studied language or history. I was the first American to go there to study music on this program.

NM: And as I understand, nobody had gone to Georgia either.

TL: I’m not sure. It’s possible that someone came later to study Georgian music on that exchange. But the Soviets didn't want Americans all over the USSR; they preferred to send them to Moscow and Leningrad so that they could keep an eye on them. However, they made an exception for me to go to Tashkent because of a connection through an American professor, Mark Slobin, who knew someone there. So I spent this year in Uzbekistan. I wrote a PhD dissertation on Uzbek shashmaqam, and after that, I actually left academe. I got my degree in 1984, and I dropped out. This was the beginning of glasnost and there was a lot of interest in cultural exchange. The cultural exchange between the USA and the USSR had ended after the Soviet Union went into Afghanistan at the very end of 1979. All the cultural exchange agreements were suspended. But there was a lot of interest, a lot of curiosity in reviving cultural exchange through citizen diplomacy. So I became one of a small army of both Americans and Soviets who were pursuing projects independently of the government to create people-to-people exchange.

NM: So, would you describe those initiatives as grassroots efforts?

TL: Grassroots, absolutely. There were people in various fields: young doctors building relationships, disarmament activists, and those interested in ESP, which the Soviets were researching. I focused on cultural exchange, bringing American performing artists to the USSR and vice versa. After leaving academe, I spent five years living out of a suitcase. When asked where I lived, I’d say, “Chemodansk.” (Chemodan means “suitcase” in Russian, so Chemodansk is like “Suitcaseville.”)

NM: Was that the time when you were pursuing a career as a music producer as well?

TL: I had a small business and we did some really crazy projects. At that time, a lot of pop stars wanted to come to the Soviet Union to realize their fantasies of glasnost, but they didn't know how to do it. And we had these contacts. The first person we brought was a country singer called John Denver. He did a tour in 1985. And then after that, a lot of other people started to come to us and say, can you bring me, and can you bring me?

NM: But was it that simple to bring Western musicians across the Iron Curtain?

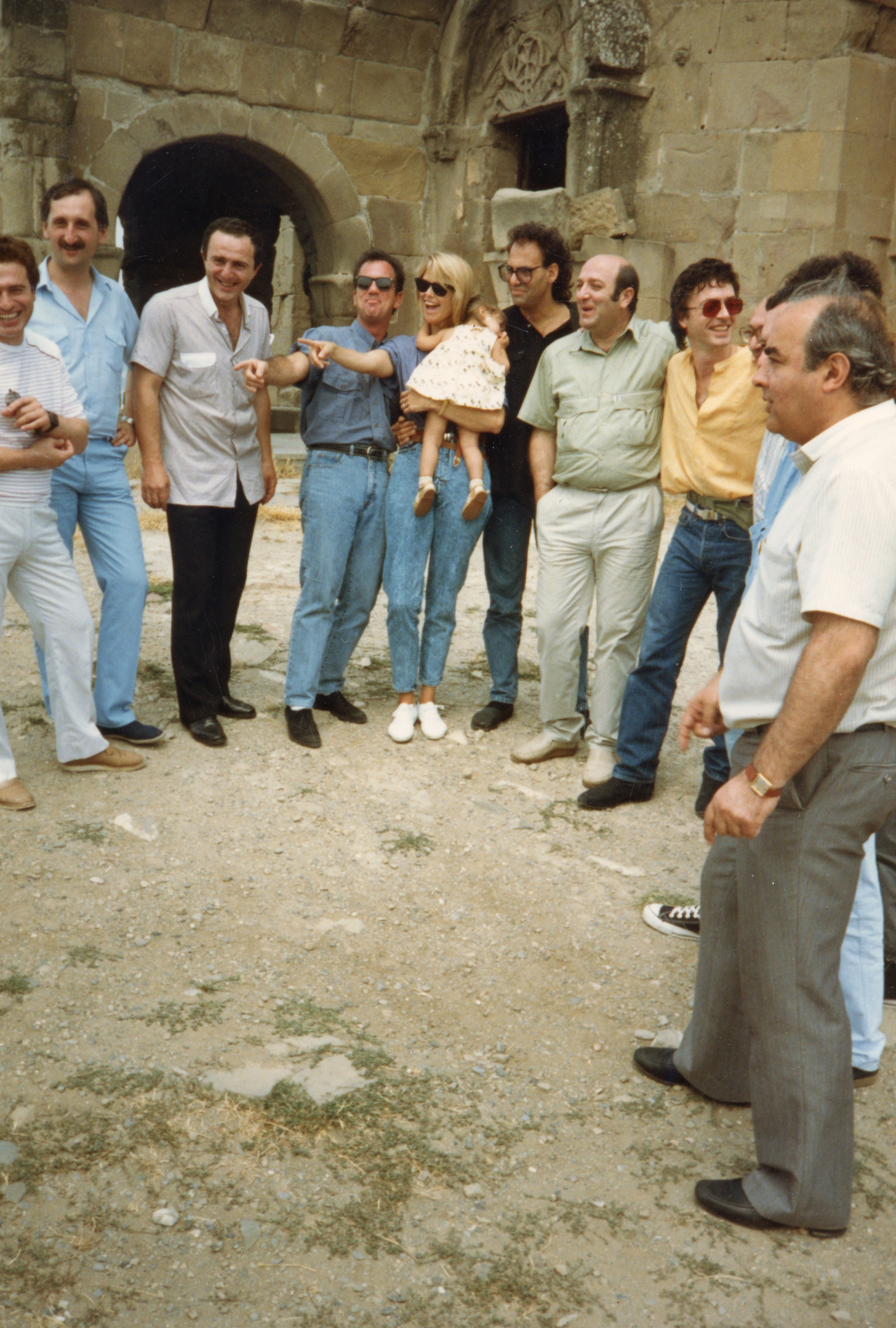

TL: It wasn't simple, but as a producer, we made it work. The first person who agreed to pay for us to go and work out a major tour was Billy Joel. In 1987, my business partner and I produced a tour of Billy Joel in the Soviet Union. We started in Tbilisi, where he did a concert in the Opera and Ballet Theater, and even tried singing Georgian music. Then we moved on to Moscow and Leningrad and did huge stadium concerts. It was the first fully staged American rock and roll tour ever to come to the Soviet Union.

Billy Joel, wife Christie Brinkley and daughter Alexa Ray Joel with Georgian hosts

Billy Joel, Christie Brinkley and band musicians with Georgian hosts

(Billy Joel with the ensemble "Journalist" (later Georgian Voices) on the stage of the Tbilisi Opera and Ballet Theatre).

NM: What was the resonance or impact of your first groundbreaking international producing project?

TL: This successful project of course created even more interest. There were a lot of people who wanted us to do special projects, and we did all kinds of things. I went twice to Lake Baikal in the middle of winter to try to record the sounds of the Baikal seal, dropping hydrophones through holes in the ice. A jazz musician named Paul Winter wanted to play his saxophone together with the sounds of the seals. He’d already played with whales and wolves, and he wanted to play with seals. Then there was another project with a famous actor, Leonard Nimoy, from an American TV show called Star Trek. Nimoy’s father was born in Ukraine, and he wanted to go to the village where his father was born. The Star Trek TV show had been made into a series of movies, and we got the movie company—Paramount—to subtitle one of these films, Star Trek IV, into Russian and we screened it in Moscow. It was a film against whaling, and the idea was to get the Soviet Union to stop whaling, which, surely coincidentally, the USSR halted not long afterward. We did the screening, and then I brought this famous actor to his father’s village in Ukraine.

NM: Did you continue pursuing such unconventional projects after those initial ventures? It seems they were less focused on music, but rather diverse in nature. And if I understand correctly, you eventually returned to exploring music in different regions of the Soviet Union.

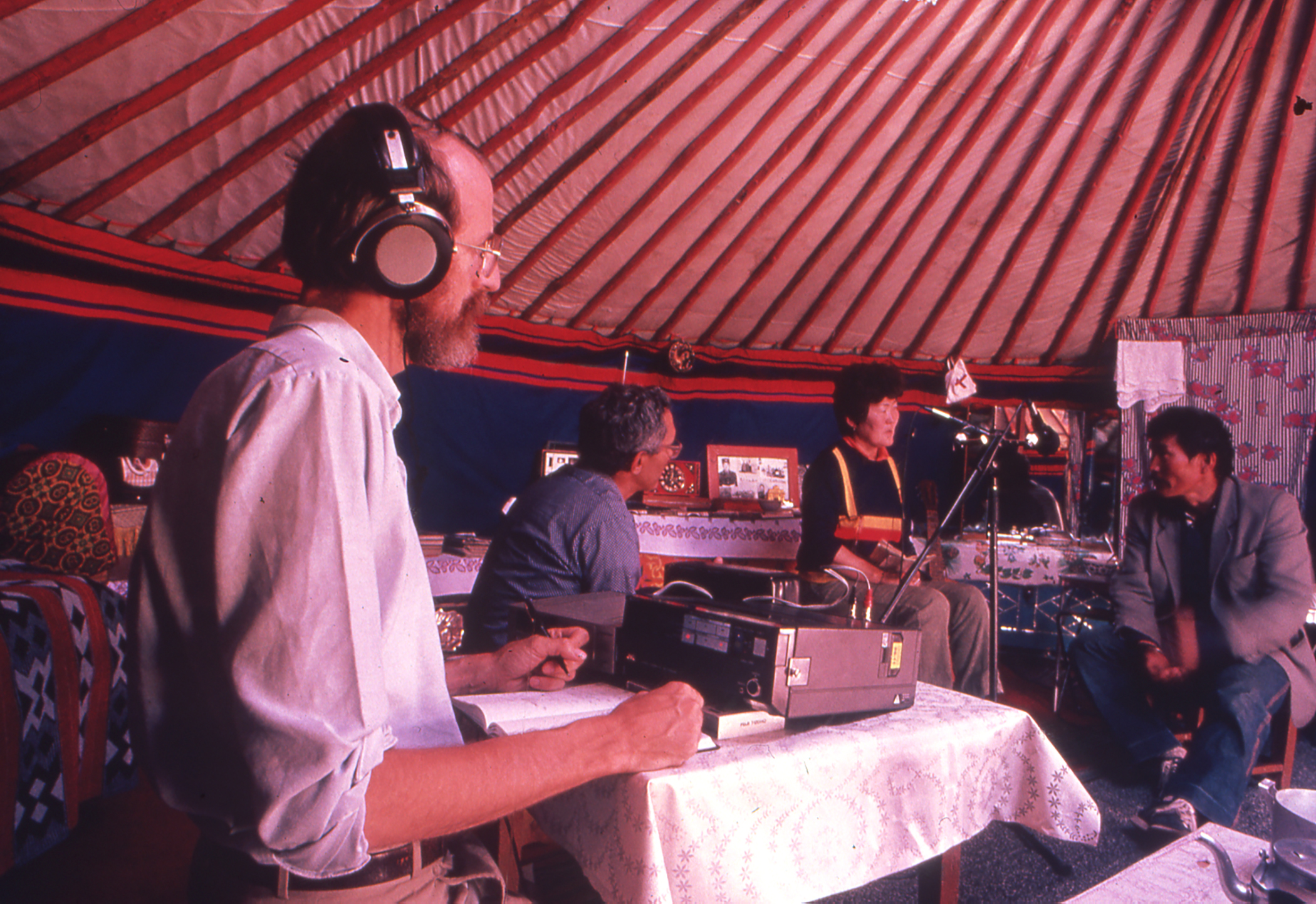

TL: After our successful collaboration with Billy Joel, our contacts at the government agency Goskontsert expressed gratitude. When they asked what they could do for me, I told them that I wanted to travel to Tuva. My request was initially met with skepticism. They couldn't understand why I wanted to visit Tuva. However, I explained my intention to record traditional music there. Despite the region being off-limits to Americans at that time due to security concerns around a nearby radar station in Krasnoyarsk, I was granted permission. Consequently, in 1987, I became the first American to visit Tuva and study its music.

Ted Levin records Tuvan throat-singers in a yurt, Tuva, 1987.

NM: So you were the first American to extensively study music in the ex-Soviet regions. You also facilitated the export of music from behind the Iron Curtain, like Georgian traditional music, which you first heard in Jvari Monastery. Was this when you met Anzor Erkomaishvili for the first time?

TL: No, I didn't meet him, of course. I was a tourist, and they didn't allow us to talk to the musicians. The next time I saw the Rustavi Choir was in 1981. I was in Paris, and Rustavi was there. They gave a concert at La Maison de la Culture, a cultural house and theater. After the concert, I stood outside the theater as the musicians came out to get into their bus. I really wanted to talk to them, to express my love for their country and music, but I was too shy. I missed that opportunity. So I watched them board their bus and drive away without making contact. However, I thoroughly enjoyed the concert and their music. It wasn't until 1988 that I actually met Anzor Erkomaishvili. That was when I was curating a part of what was then called the American Folklife Festival, now known as the Smithsonian Folklife Festival. It’s a large festival held outdoors on the National Mall of the United States in Washington, D.C. It’s been running every year since the late 1960s.

Ted Levin with Anzor Erkomaishvili and Levon Abashidze, around 1994.

NM: How did the involvement of Georgians come about at the festival?

TL: That year, the Smithsonian Institution, our national network of museums, organized a cultural exchange with the Ministry of Culture of the Soviet Union. Given my experience in cultural exchange, they asked me to facilitate this exchange and to curate. So, I insisted on having Georgian music at the festival. The Ministry of Culture reached out to their representatives and to Anzor. Instead of bringing the Rustavi Ensemble, we aimed for an authentic folk choir, not a professional one. Anzor chose Elesa from Guria. He also served as a sort of liaison, not exactly an artistic director, but facilitating the process. Although I knew nothing about Georgian music, the protocol of the festival required that musicians perform in tents with small stages seating about 50 people. Each group would perform four times a day in these tents, and an American presenter associated with the festival would explain something about the music on stage. So, I was that presenter. The only problem was, I didn't know anything about the music. Anzor was there, and before each song, he would quickly explain it to me in Russian. We spoke Russian together. I’d then get up on stage and repeat what Anzor had told me. At night, there were incredible jam sessions with musicians from different groups. Since there weren’t many people who spoke Russian, I became good friends with Anzor during the festival.

Elesa Choir with Anzor Erkomaishvili at the Smithsonian Festival of American Folklife in Washington, D.C., summer 1988.

NM: I know that it was you who assisted him with those archive records, which shed light on the history of early twentieth-century traditional musicians and music. How exactly did you help him?

TL: At the end of the festival, Anzor suggested, “I have this group, Rustavi Choir,” which, of course, I knew because I’d seen them in Paris and I had their record albums. He said, “Why don't you release a compilation of our music in the United States?” And I thought, “Wonderful, I'd love to do that.” So, I arranged for Nonesuch Records, which was then part of a big record conglomerate (Warner-Elektra-Atlantic) to release a compilation. In 1989, I came to Tbilisi, chose the music with Anzor, and wrote liner notes. The record was a big success. The next year, Anzor wanted to go to London to search for early recordings of Georgian music in the archives of EMI. I met him in London, and together we found the recordings, including those of his great-grandfather, Gigo Erkomaishvili. It was very exciting.

NM: So you played a key role in this project?

TL: Well, I was involved, but I wouldn’t say I was the key person. Initially, the plan was for the recordings to be released on the OCORA label in Paris, the label of Radio France. I had connections with OCORA, having worked with them before. However, despite promises, the deal fell through when the director I knew left. Then, several years later, Carl Linich stepped in. He knew about the recordings and took on the project. He eventually arranged to have them released on the Traditional Crossroads label as a CD titled Drinking Horns & Gramophones 1902-1914: The First Recordings in the Georgian Republic (2001).

NM: Considering your return after fifty years and your observations of developments and changes, there’s undoubtedly much to discuss. So, reflecting on your initial experiences here, particularly your involvement with recording groups and choirs, including those from villages, what transformations have you noticed during this time?

TL: When I first came in 1974, it was as a tourist, and my time here was brief, maybe less than a week. I was mainly in Tbilisi, and after leaving Tbilisi, I drove to Sukhumi. Back then, the Rustavi Choir was only about six years old. Official performance spaces were monopolized by the state, with limited opportunities to hear music outside of formal concerts or estrada music performed in restaurants. It's remarkable to think that in 1974, Tbilisi had just a handful of restaurants.

NM: It’s almost like traditional music and restaurants made a pact to grow together! Just like how Tbilisi went from a handful of restaurants to a bustling food scene, we've seen the same explosion in the number of choirs and ensembles [laughing].

TL: A section of the book I’m writing is called “A Polyphony of Polyphony,” meaning that there's just tremendous variety now. I’m so impressed with the variety of music that you can hear in Tbilisi. I haven't been here a long time, but in a couple of weeks, I’ve heard music that extends from more or less authentic representations of older styles, both in liturgical singing and folk singing, to what I’ve called neotraditionalism, that is, people being more free in the way they interpret traditional music. I heard this wonderful group, Iriao.

NM: I’m eager to explore neotraditionalism and your involvement with this music further. In your recent presentation, you touched on some intriguing aspects we could delve into. You mentioned your reservations about ethno-jazz due to certain clichés. Could you elaborate on that?

TL: I do have reservations about ethno-jazz, except when it’s really good. And Iriao are really good. We went to a rehearsal, and I just loved it. Their music has nothing to do with clichés.

NM: Is this because they simply employ the Georgian music vocabulary to create their own unique compositions?

TL: Exactly. After hearing them live, I went and listened to everything I could find on YouTube. They’ve got a new drummer and a new bass player now who are dynamite, they’re just fantastic. The group has never sounded better than it does now. It’s tremendously creative and imaginative. And were Basiani not performing tonight, I’d be going to Rustavi to hear Iriao’s concert at 10 p.m. I just love that group. They set a high bar for ethno-jazz.

NM: So, would you label their compositions as ethno-jazz?

TL: Well, they did. I asked them, and they said that yes, what they perform is ethno-jazz.

NM: Do you agree with this assessment? And do you believe it's necessary to assign a specific label to such bands?

TL: Musicians don't like labels. They always resist. I remember once I was on a panel discussion with Gia Kancheli in New York. He was with some other famous musicians who had been lumped together into a category called “mystical minimalists.” And each one of them said, no, I don't like that.

NM: Because it’s more nuanced than that. You probably can't just categorize it because it transcends traditional boundaries. Although they [Iriao] still refer to themselves as playing ethno-jazz.

TL: They said it's just practical. If you need to explain to a festival director what kind of music you do, you can say “ethno-jazz.” This will also tell you where to look for it in a store. Anyway, Iriao are obviously doing something that’s very original. I also met with Niaz Diasamidze. I love Niaz's music. I wasn’t able to hear a rehearsal, but I’ve listened to a lot of what’s online of his, and we talked nicely for an hour. And he’s very sincere about his wish to touch people. We were speaking in French, and he kept talking about frisson, goosebumps] And he said, “This is my aim, to create this feeling in people.” I’m going to write a chapter about him called Panduri Rock. He uses the panduri like a rock and roll instrument. It’s very imaginative, and I like what he does with it.

NM: Your musical journey seems incredibly diverse…

TL: Yes, I went to hear Rezo Kiknadze. And he's an incredible musician. He’s got these three musical lives that don’t intersect. He plays fantastic jazz saxophone. He’s an accomplished composer who works in cutting-edge electronic and digital music, and he was singing liturgical chant with Anchiskhati Choir. We asked him, do you use folk music influences? And he said, no, I don’t, because that's what you were forced to do in Soviet times and I want to resist that. I want people to know that’s not what I do. His composed music is utterly different from Georgian folk music. So there's this very wide spectrum that I’ve seen.

NM: With that in mind, how does the diversity and intensity of the musical landscape in Georgia today compare to other regions you've explored?

TL: You can see a trend in many countries now, wherein traditional music gains acclaim thanks to its popularity in other cultures. It sounds kind of cynical to say that the way to build popularity for your music is for it to be popular somewhere else. But the fact is, this is a strategy that works. Take Tuva, for instance. Despite its small population (300,000 people), throat singing, which was discouraged as a performance genre under the Soviets, gained global popularity after 1991. This success inspired dozens of ensembles in Tuva, sparking a revival. Similarly, Georgian music has witnessed a surge in interest, with foreigners drawn to polyphonic singing because of its participatory nature, fostering a vibrant international community. Ireland is another place where there's a huge musical revival. A lot of young people are playing it virtuosically. I also went to Ireland fifty years ago, and the music is much more alive now than fifty years ago. Particularly among young people. And of course it’s being played all over the world.

NM: So, based on your observations, do you reckon the surge of neotraditionalism poses a threat to traditional music forms and heritage?

TL: The book I’m writing now is meant to challenge, to push back on discourses that circulate, particularly in the world of UNESCO and among ethnomusicologists, about endangered traditions in urgent need of safeguarding and preserving. Yes, there are such traditions, but there's also a huge amount of musical talent among young people. And they’re doing a lot of interesting and imaginative things with traditional music all over the world. And here in Georgia, that's absolutely true.

NM: Often, traditional music is seen as a single domain, leading to neotraditional forms being judged as mishandled or cheapened versions of the “authentic” music that should be preserved without alteration.

TL: I would say that it’s mainly people in academe who say, “No, we must preserve the authentic form, and you shouldn't be trying to create these neotraditional versions.” My feeling is that there's room for everyone. I believe that it's very important to preserve older forms of music for future generations so that they too can have access to these older singers and receive inspiration from them. So of course, we should document; of course, we should preserve; of course, we should safeguard. But you can't stop people from extemporizing, from innovating. That's what musicians have always done and that's what keeps music alive. Everyone says this, everyone knows this—that to remain alive and vital and relevant, traditions must evolve. And so I think you need a wide spectrum of musical activities, ranging from people who are interested in historically informed performance, people who are documenting, people doing ethnography, recording old singers to try to preserve their styles, and people innovating and developing their own imaginative responses.

NM: This raises a question about understanding the broader context of the concept of “folk music.” In its classical standard definition, one of its features is that it has no single author and is the product of elaboration, sometimes over generations. However, in the West, contemporary musicians who compose songs can also be considered folk musicians or singers.

TL: Every song has an author, and the only reason you don't know the person's name is that it's been lost. And so you can try to recover it. But folk music, at least in the United States, ranges from performers who are reviving old styles in more or less authentic ways, to singer-songwriters who are composing new songs. Joni Mitchell, for example. She’s a folk singer. Joan Baez, she’s a folk singer. One of the things that I’ve found sort of puzzling here in Tbilisi is that in a lot of the meetings we’ve had with choirs, I've asked, are you writing new songs? No. They don't write new songs. They make versions or new variants, arrangements of old songs. Whereas in the West, folk groups are always writing new songs. They play older songs, but they’re writing new songs. There seems to be some division here in which the so-called folk choirs, polyphonic choirs, are not adding to the repertoire. They’re doing their version, but they're not composing. And then there's this whole other world consisting of people like Niaz, who are writing, but that’s something else.

NM: So much to discuss and go into but this can be an endless process. Well, Ted, it’s been a pleasure discussing music with you today. Your insights have been truly enlightening, and I'm sure our audience will find them just as fascinating as I have. Thank you for taking the time to share your knowledge and experiences with us.

%20%E1%83%9C%E1%83%90%E1%83%9C%E1%83%90%20%E1%83%9B%E1%83%9F%E1%83%90%E1%83%95%E1%83%90%E1%83%9C%E1%83%90%E1%83%AB%E1%83%94%20-%20%E1%83%98%E1%83%93%E1%83%94%E1%83%98%E1%83%A1%20%E1%83%90%E1%83%95%E1%83%A2%E1%83%9D%E1%83%A0%E1%83%98%2C%20%E1%83%A1%E1%83%90%E1%83%A0%E1%83%94%E1%83%93%E1%83%90%E1%83%A5%E1%83%AA%E1%83%98%E1%83%9D%20%E1%83%A1%E1%83%90%E1%83%91%E1%83%AD%E1%83%9D%E1%83%A1%20%E1%83%AC%E1%83%94%E1%83%95%E1%83%A0%E1%83%98-min.jpg)