Intervew with Malvina Mukbaniani

Malvina Mukbaniani was born in 1946 in Lentekhi, in the village of Chvelieri. I first saw photographs of her work in the archives of the Folklore Center and was immediately fascinated by their ethnographic quality, their outstanding ability to convey Svan traditions, history, and legends.

Later, I met Malvina in Tbilisi, and we organized an exhibition of her work at the Folklore Center. I will never forget the fascinating stories she shared about her native region and her ancestors; her works tell these stories colorfully and with amazing accuracy. In my opinion, all of Georgia should be familiar with Malvina Mukbaniani’s work.

We visited Malvina at her home in Chvelieri and recorded an interview that will give us a glance into this artist’s inner world and the sources of her creative inspiration.

Gocha Balavadze

When and how did you start painting?

My first steps into art started at school. Back then, boys from my class often came and asked me to draw something for them. I usually complied and fulfilled their wishes. When it was time to choose a profession, I wanted to enroll in the Tbilisi State Academy of Arts, but my father didn’t let me. [He would say,] “a girl shouldn’t be messing with colors; you’ll be like Benia Babluani with paints in your hands.” Benia Babluani was a self-taught artist who worked in the publishing house. He had a workshop and a small gallery where he exhibited his own works. It was there that I saw how paintings were made for the first time. He loved to draw people and created wonderful characters. I would like to recall one painting: it was of Dali [a Svan goddess of the hunt] with disheveled hair, standing on a rock. Unfortunately, no one else noticed this painting—Benia’s work was not known to the general public. But back to my story: I graduated from school with a gold medal, was rejected from the Academy of Arts, and finally decided to go in the direction of biology, because I thought that biology was still related to life, so it seemed interesting to me. I successfully completed my studies in biology and returned to Lentekhi, where I started working as a schoolteacher. But life still brought me back to painting. It so happened that the school didn’t have an art teacher. The principal knew that I could draw and paint and offered me the job of art teacher, and I happily agreed. Before I became an art teacher at the school, no one from Kvemo Svaneti had enrolled in the Academy of Arts. Therefore, I am proud that ten of my students got into the Art Academy and chose painting as a profession.

What can you tell us about your first work? Which was it, and how was it created?

When I realized that I wanted to make a full-scale painting, first of all I found out where the canvas was sold and had a frame specially made. I remember how my brother helped me stretch the canvas. I still have my first work at home today. I called it “Woman at the Sea.”

You have a distinctive “signature”: the main themes of your work are ethnographic. What made you choose this direction?

This style was formed later, when I realized that the old customs were being lost. For example, I saw that many people no longer practiced Lipanaali [the Svan ritual of hosting the spirits of the deceased and entertaining them]. Some traditional practices were also lost, such as, for example, the old method of washing wheat. I also knew that the machubi [the residential house in Svaneti] would soon become a thing of the past. Besides, I didn’t want to forget the old stories that my grandfather used to tell me. So, I decided to preserve them in this form and started painting. I think that I kept these traditions alive through my paintings.

What is your workflow? How do you come up with your ideas, impelement them, and then transfer them to the canvas?

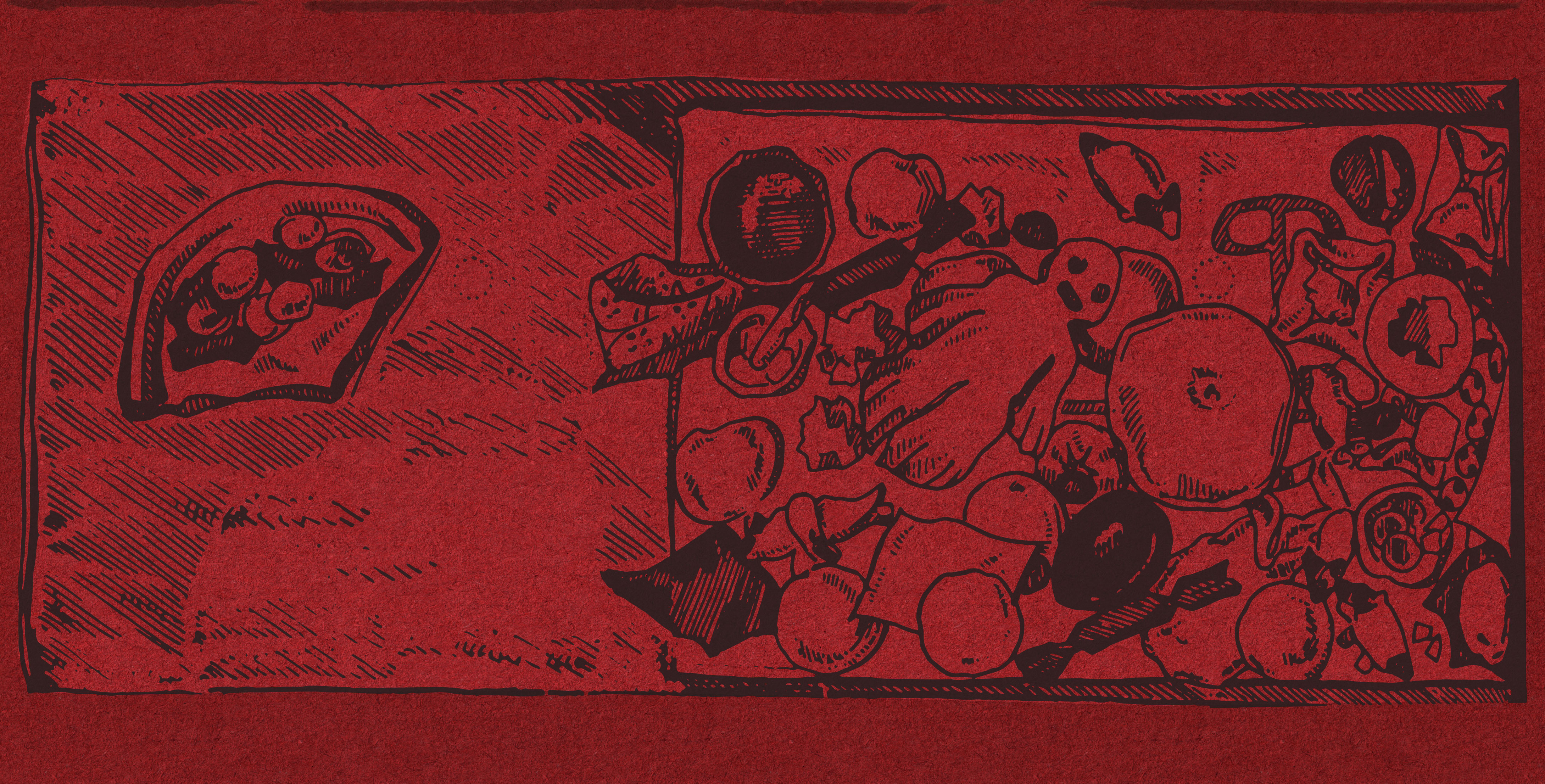

I can tell you that I never make sketches. I would always have in mind what I wanted to paint, and I would prepare the canvas right away and start painting. I never had an easel either. I asked the art school for one several times, but they never gave me one; I really did want it. Unfortunately, I don’t have a lot of time to paint, so as soon as I have a chance and one or two hours free, I paint right away, although it doesn’t happen that often. As for the time, I only paint during the day, because the colors change at night. I regret that I used to give away my paintings easily; thinking about it now, I would have done it differently. One story comes to mind on this topic: I loved poetry very much, I wrote poems, and I had really wanted to publish them, but unfortunately my poems were never printed. So, I took a still life painting, which I really liked, went over to the deputy editor and gave it him. He liked it a lot, and he was grateful and helped me publish a collection of poems. Five thousand copies were issued and sold by the state. In short, the still life printed my poems.

What are your personal aesthetic principles that you realise in your paintings?

In my opinion, this topic is subjective, and it is for each artist to decide which aesthetic suits which topic. This is a skill that cannot be taught. An artist must create the piece in their mind and then transfer it to the canvas. I don’t know about anyone else, but that is what I do. When I see it clearly in my mind, then I start painting. That’s why I never change it. However, I imagine it from the beginning, that is what I paint to the end. I really try to make what I paint look just like what I have in mind, so painting is very challenging. If it doesn’t turn out the way you have in mind, you have to erase it and repaint it until it does. I never had many brushes. Sometimes, when I didn’t like the size of the brush, I would wrap cotton around a stick and paint with it, or even paint with my finger. I have worked with a sponge as well. A sponge covers evenly; it doesn’t leave strokes. In a word, the main thing is the desire to do what you love.

What about colors—which color is the most important to you?

By mixing, we can get millions of colors, all kinds of colors are possible. I personally love the color of the sun, and black is also very important. Without it, you can’t depict anything, because you can’t have a picture without a shadow. I’ve always wanted to paint a rainbow, but I never got it the way I imagined. However, I managed to partially do this in one of my paintings, which is about the Muses. Three months went by, and I had the idea of painting each Muse with one color of the rainbow, as Rustaveli wrote with a goose’s feather. I drew an eye next to this goose feather. It’s a visual perception of reality, and that’s how the muse is born. One muse is unattainable, and that is the idea of God. I also used the moon in the painting, behind which part of the eye is visible. In the end, I’m not very fond of this piece, but maybe I will come back to it again.

How often do you paint? What prevents you from working?

As I told you, I don’t have much time for painting, unfortunately. The pandemic added to all this; it hindered me a lot. We were all very sick in the family. My brother, who was a great person and very educated, too, unfortunately did not survive and died. It affected me a lot, and I can’t think about painting anymore. I have one nephew left, to whom I will leave my paintings.

Tell us about your ancestors.

I want to tell you about my grandfather. My grandfather was a “man of the icon” [responsible for keeping a local shrine]. He was entrusted with the temple money and never spent it on his family. I would say that this is true “aristocratic thinking,”, and if it is to be found anywhere, it is definitely here. I also want to say with a heavy heart that the Svan language is being lost. The Svan traditions, the rituals that were performed in Svan families, are no longer there. Although we are peasants, with God’s blessing, we follow all the family rules, so that there is no anger. I try to capture these rituals in my paintings, so that they remain for the future.

How do you come up with an idea that then turns into a painting?

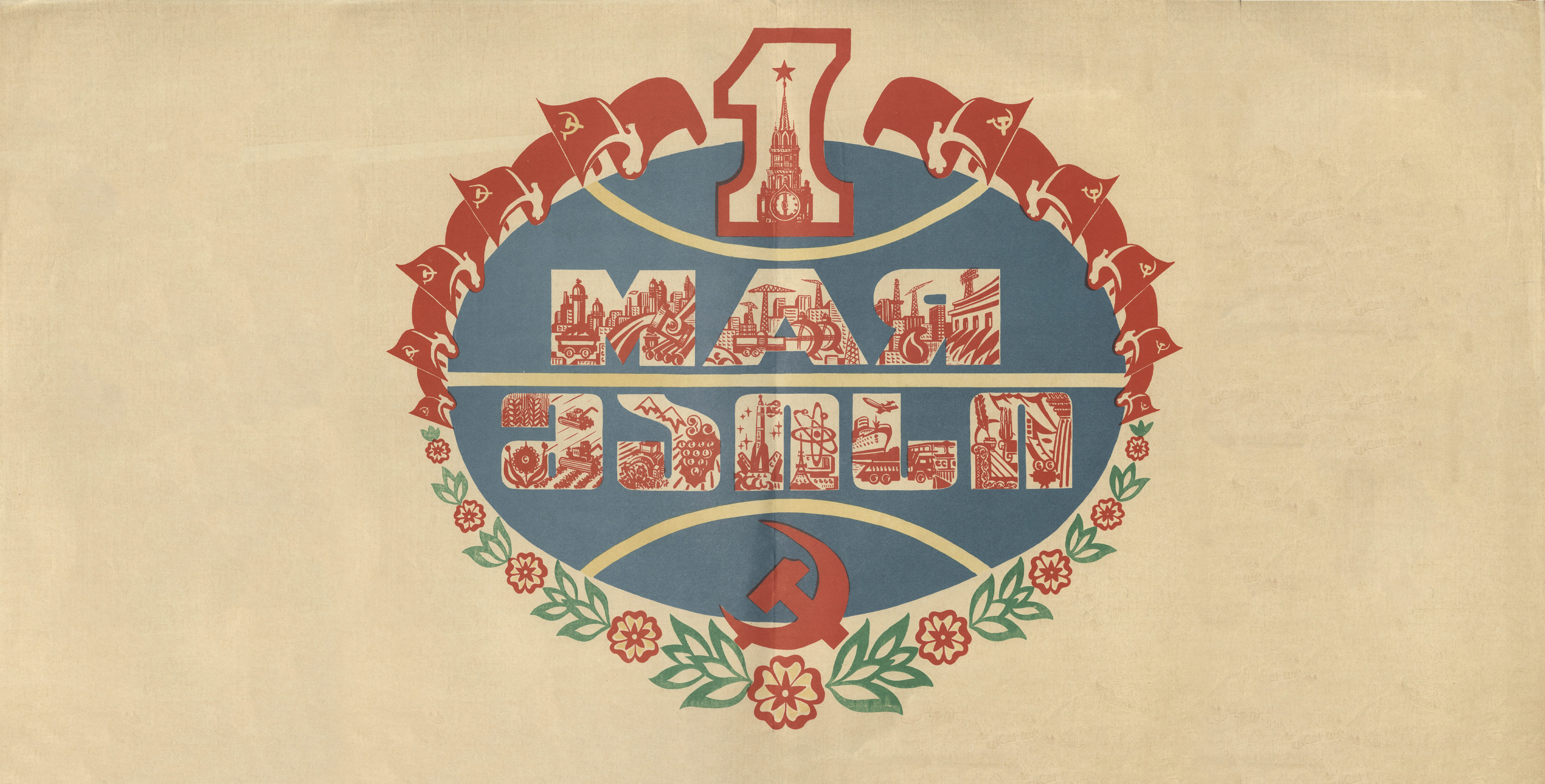

I have one painting on the subject of politics, in which I depicted the confrontation between the Soviet Union and the traditional way of life. This was one of my first works. I saw that there was a conflict with religion: churches were destroyed, the old, traditional religious rituals were forbidden. I didn’t like this. I had my family as an example—how they respected the traditions. At the same time, our family was also protecting icons of the local shrine. Politics and religion were in opposition to each other. I was thinking about how to paint this. “Politics” was represented by the shape of a star, which was a symbol of the Communists. In short, I painted our fireplace with a star on it. Below, in the fireplace, I showed the preparations for a religious ritual. How to paint politics? I thought about it for three months, and as soon as I came up with it, then suddenly everything became clear and the picture appeared in my mind. I would come from school at three o’clock, eat, and start painting until it got dark. I gave myself one month to complete it.

What about your future plans? Do you have an idea of what you want to do?

I have one idea that I would like to work on. I’m a little bit nervous, because it’s something of a religious topic. I am thinking in what position to paint it. I can imagine the picture like this: the priest enters, the table is set, and a man is standing behind the table, besieged by monkeys. The priest, he has a candle in his hand, and these monkey-like creatures run away from him. I don’t know how and when I will be able to do it, but I have been wanting to paint it for a long time, and I have prepared a canvas. My sister and I have a large farm, fertile fields; we are planting a vegetable garden. We have cattle, pigs—it’s not always easy. We have frequent visitors, a lot of relatives, and it is a bit difficult to make time for painting, but I will try to bring this idea to the end.

%20%E1%83%A1%E1%83%90%E1%83%9C%E1%83%93%E1%83%A0%E1%83%9D%20%E1%83%9C%E1%83%90%E1%83%97%E1%83%90%E1%83%AB%E1%83%94%20-%20%E1%83%9E%E1%83%A0%E1%83%9D%E1%83%94%E1%83%A5%E1%83%A2%E1%83%98%E1%83%A1%20%E1%83%AE%E1%83%94%E1%83%9A%E1%83%9B%E1%83%AB%E1%83%A6%E1%83%95%E1%83%90%E1%83%9C%E1%83%94%E1%83%9A%E1%83%98%2C%20%E1%83%A1%E1%83%90%E1%83%A0%E1%83%94%E1%83%93%E1%83%90%E1%83%A5%E1%83%AA%E1%83%98%E1%83%9D%20%E1%83%A1%E1%83%90%E1%83%91%E1%83%AD%E1%83%9D%E1%83%A1%20%E1%83%AC%E1%83%94%E1%83%95%E1%83%A0%E1%83%98-min.jpg)