The Adventure of the Chonguri

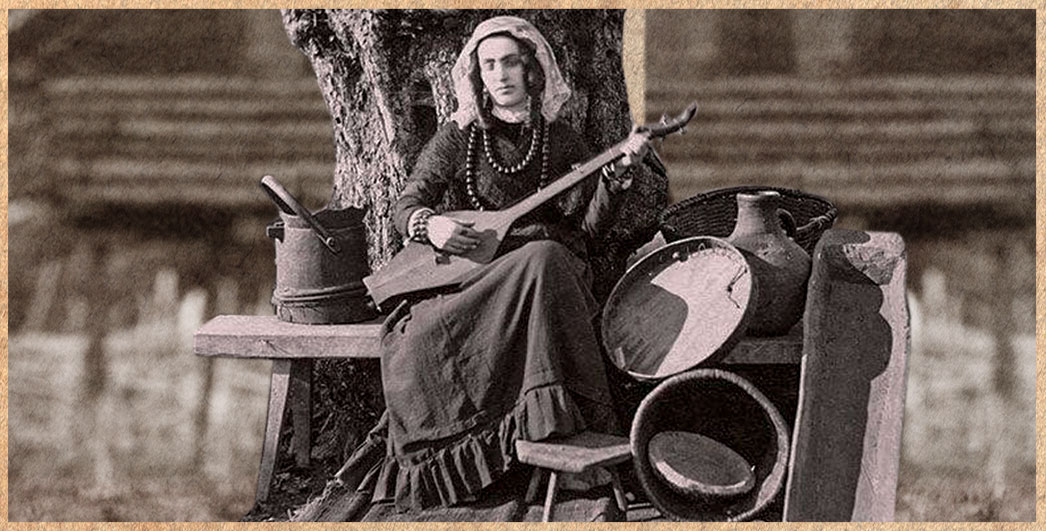

The history of the chonguri, one of the most popular instruments in Georgia, is not particularly simple nor clear. Information about the term chonguri does not appear in primary sources from the Middle Ages, nor in the eighteenth-century dictionary of the Georgian writer Sulkhan Saba Orbeliani, Sit’qvis k’ona (A collection of words), which for Georgians serves as a link between the terminology of the Middle Ages and modern times. Although this term is not found in written sources, we find an interesting sketch in the travel notes of Cristoforo Castelli, a Genoese missionary who lived and worked in Georgia between 1628-1654, depicting a scene in Guria in which a woman plays chonguri for a child.

The chonguri is commonly played in western Georgia, that is, in Guria, Samegrelo, Imereti, Ach’ara, and Abkhazia. However, the term chonguri often appears in the vernacular and oral folklore of eastern Georgia as well, where it is used in reference to another popular folk instrument, the panduri:

“He/she played the chonguri well,

The pride of Tusheti” (1)

“Chonguri, my chonguri,

cut from a distant pear tree” (2)

The instrument called “panduri” in Tusheti and Khevsureti is the same as the one referred to as “chonguri” in Kartli-Kakheti. That is why the historian Ivane Javakhishvili considers the terms panduri and chonguri to be synonymous. According to the ethnologist Manana Shilakadze, the name chonguri originates from the seventeenth century, which is when a fourth string was added to the panduri.

© STATE MUSEUM OF GEORGIAN FOLK SONGS AND INSTRUMENTS

However, in addition to the number of strings, the panduri differs from the chonguri in its volume and the way the strings are tuned. Information on these technical differences can be found in abundance both on the internet and in various literature (see suggestions for further reading below), but a few features still warrant special attention. The panduri, unlike the chonguri, has frets along its neck, which can make it easier to find chords, even for beginners. Playing the chonguri therefore requires more skill in this regard, as even a slight positional deviation of the fingers changes the notes on the strings. A lot depends on the performer's “ear” and their experience. Because the chonguri is fretless, however, it also allows for more room for improvisation, which is built-in to the techniques of chonguri playing. It can be played by plucking or strumming the strings, up or down. It also has the added function of a percussion instrument for dance melodies such as the khorumi and gandagana.

Audio Sample 1

The additional fourth string on the chonguri allows for greater variety in tuning, expanding the repertoire that can be played on the instrument. Each of the strings of the chonguri is referred to by the same terms as voices in Georgian polyphonic singing: the first string from the bottom is called the mtkmeli or “narrator,” the same as the “first voice” in singing, ; the second string from the top is the modzakhili or “caller”, like the second voice); and the top, lowest string is the bani or “bass.” There is also a shorter, drone string known as the zili, which is often called ts’vrili or “thin”, the same term used for the vocal techniques of k’rimanch’uli and gamqivani in Guria and Adjara.

Today, both men and women play chonguri indiscriminately. However, the scene described by Cristoforo Castelli accurately reflected the chonguri’s role at the time as a women's instrument. It is known that the chonguri was an important part of a woman’s dowry. In 1971, during Manana Shilakadze’s expedition in the village of Shua Surebi in Guria, 73-year-old Maro Trapaidze-Berishvili recalled: “Every man knew how to play chonguri, but women played more.” (1) They would play dance melodies, lullabies (perhaps a later development), and ballads on the chonguri. Women playing the chonguri had an important role in the Bat’onebi rituals, which were connected to the treatment of infectious diseases, especially in children.In Guria, for example, such rituals might involve nine women, representing different families, gathering together and singing the song known as “Sabodisho” or “Bat’onebo.” (2) According to tradition, men did not sing “Batonebo.” In Samegrelo, the funeral procession of a person who died of a Bat’onebi infection was accompanied by chonguri melodies. (3).

Audio Sample 2

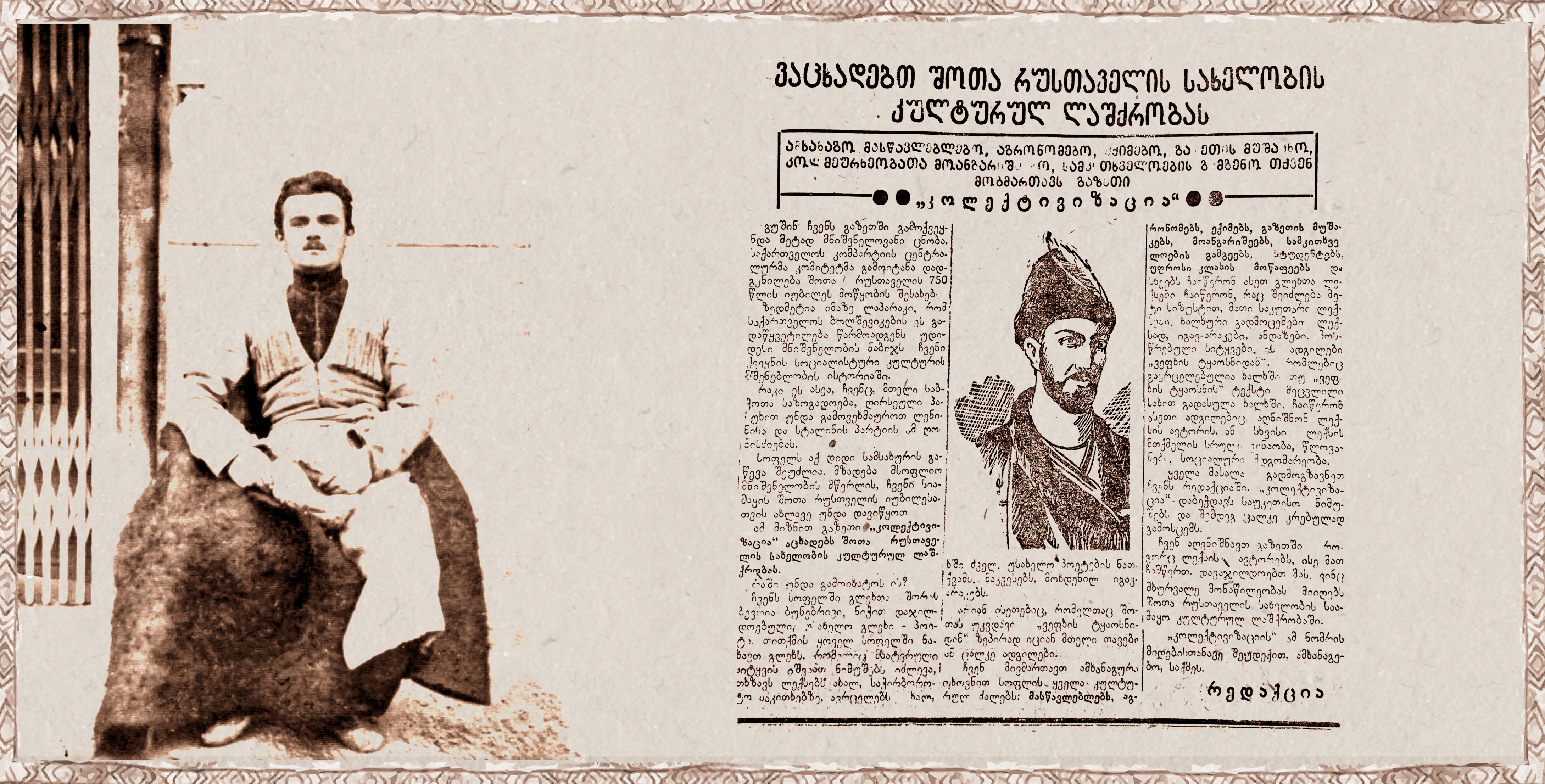

The connection between women and the chonguri is also evident in ensembles formed in the first half of the twentieth century, such as the famous women’s mechongure (“chonguri players”) ensemble led by Avksenti Megrelidze, the popularity of which led to the addition of women chonguri playersto all district ensembles in Guria. With the establishment of mass performance forms in the Soviet Union, the traditional approach was abandoned, and, in these large ensembles, several chonguri were played at the same time. In this way, the element of individualism was entirely lost, which could be seen as the result or a reflection of the influence of Soviet ideology.

Starting in the second half of the twentieth century, the connection between the chonguri and women began to break, and today the chonguri is no longer so stronglyassociated with women. Gradually, the chonguri and the singing of the Bat’onebi songs was taken over by men. History has thankfully preserved the recordings of master women chonguri playerssuch as Kionia Baramia-Akobia, Elene Chubabria, and others.

Let us not forget that, in addition to women, we also know of many virtuoso male chonguri performers. One of the famous masters was Samuel Chavlesvili, often called the revolutionary of Gurian song, who, as they say, learned first-voice variants by listening to birds. In order not to forget them, the story goes, he would play the tunes he “learned” from the birds on the chonguri. Kotsia Khukhunaishvili, a well-known Gurian singer from Zemo Aketi, was also a virtuoso master of the chonguri, who, they say, at one point played the chonguri with one hand while crossing himself with the other. The chonguri fell into the hands of many such interesting people, whose stories would be very difficult to tell in one article. However, we cannot fail to mention such outstanding chonguri players of different eras such as Grigol Garuchava, Husein Bajelidze, Vladimer Eremadze, Amiran Beradze, and others.

© STATE MUSEUM OF GEORGIAN FOLK SONGS AND INSTRUMENTS

The chonguri is still not especially popular or widespread in Georgia, although there is growing interest in Georgian folk instruments among young people, including the chonguri. The chonguri has also been the subject of academic research, which we hope will continue to grow and deepen, as there is still much to study and learn.

This kind of practical and academic interest in the chonguri determines its vitality. The adventure of the instrument continues, and we hope to bring to you more of its fascinating stories in the future.

References:

- 1.Javakhishvili, Ivane. 1990. Kartuli musik’is ist’oriis dziritadi sak’itkhebi (The main issues in the history of Georgian music). Tbilisi: Khelovneba, 142.

- 2.Kakhetian folk song “Chonguro,” Telavi Ethnographic Ensemble, choirmaster Piruz Makhatelashvili (recorded in the 1950s). https://audiomack.com/folkcentre/song/track-3-3?fbclid=IwAR0Fp_GmC-AmrRz23ay3MM4143PywqyLkF4Zzoq0C8tUoA8eeYsUiIx_VcI

- 3.Interview with Maro Trapaidze-Berishvili, seventy-three years old, in the village of Shua Surebi (Chokhatauri municipality), 1971. Manana Shilakadze, fieldnotes from the Guria-Ach’ara Ethnographic Expedition, 6.

- 4.Interview with Elene Kakulia-Sikharulidze, eighty years old, in the village of Gogolesubani (Chokhatauri municipality), 1971. Manana Shilakadze, fieldnotes from the Guria-Ach’ara Ethnographic Expedition, 22.

- 5.Interview with Dunia Gegenava, forty-seven years old, in the village of Zeta Teklati of the Senaki municipality (former Tskhakaya district). 1973. Manana Shilakadze, fieldnotes from the ethnographic expedition in Samegrelo (Tskhakaya and Khobi districts), 15.

Further Reading:

- 1.Javakhishvili, Ivane. 1990. Kartuli musik’is ist’oriis dziritadi sak’itkhebi (The main issues in the history of Georgian music). Tbilisi: Khelovneba.

- 2/Alavidze, David. Kartuli da sakartveloshi gavrtselebuli khalkhuri musik’aluri sak’ravebi

- 3.(Folk musical instruments common in Georgia). Tbilisi: Khelovneba.

- 4.Shilakadze, Manana. 1970. Kartuli khalkhuri sak’ravebi da sak’ravieri musik’a (Georgian folk instruments and instrumental music). Tbilisi: Metsniereba.

- 5.Shilakadze, Manana. 1988. Kartuli khalkhuri musik’aluri t’raditsiebi da tanamedroveoba (Georgian folk music traditions and modernity). Tbilisi:

%20%E1%83%A1%E1%83%90%E1%83%9C%E1%83%93%E1%83%A0%E1%83%9D%20%E1%83%9C%E1%83%90%E1%83%97%E1%83%90%E1%83%AB%E1%83%94%20-%20%E1%83%9E%E1%83%A0%E1%83%9D%E1%83%94%E1%83%A5%E1%83%A2%E1%83%98%E1%83%A1%20%E1%83%AE%E1%83%94%E1%83%9A%E1%83%9B%E1%83%AB%E1%83%A6%E1%83%95%E1%83%90%E1%83%9C%E1%83%94%E1%83%9A%E1%83%98%2C%20%E1%83%A1%E1%83%90%E1%83%A0%E1%83%94%E1%83%93%E1%83%90%E1%83%A5%E1%83%AA%E1%83%98%E1%83%9D%20%E1%83%A1%E1%83%90%E1%83%91%E1%83%AD%E1%83%9D%E1%83%A1%20%E1%83%AC%E1%83%94%E1%83%95%E1%83%A0%E1%83%98-min.jpg)