Amirani — the hero of the Georgian folk epic

Amirani is a very distinctive character in Georgian lore, a warrior hero connected with creation. Transmitted orally, the Epic of Amirani exists in many versions. When comparing the texts, it becomes clear that the hero’s biography acquired different nuances in every part of Georgia, even if the basic outline of the story is commonplace: Amirani becomes equal to the gods and is punished with eternal trials.

Amirani’s story follows a traditional model of the hero’s journey. According to this template, the lives of all epic characters include similar episodes, with such motifs as a miraculous birth, an extraordinary origin, and a struggle with a hostile force.

Amirani’s Remarkable Nature

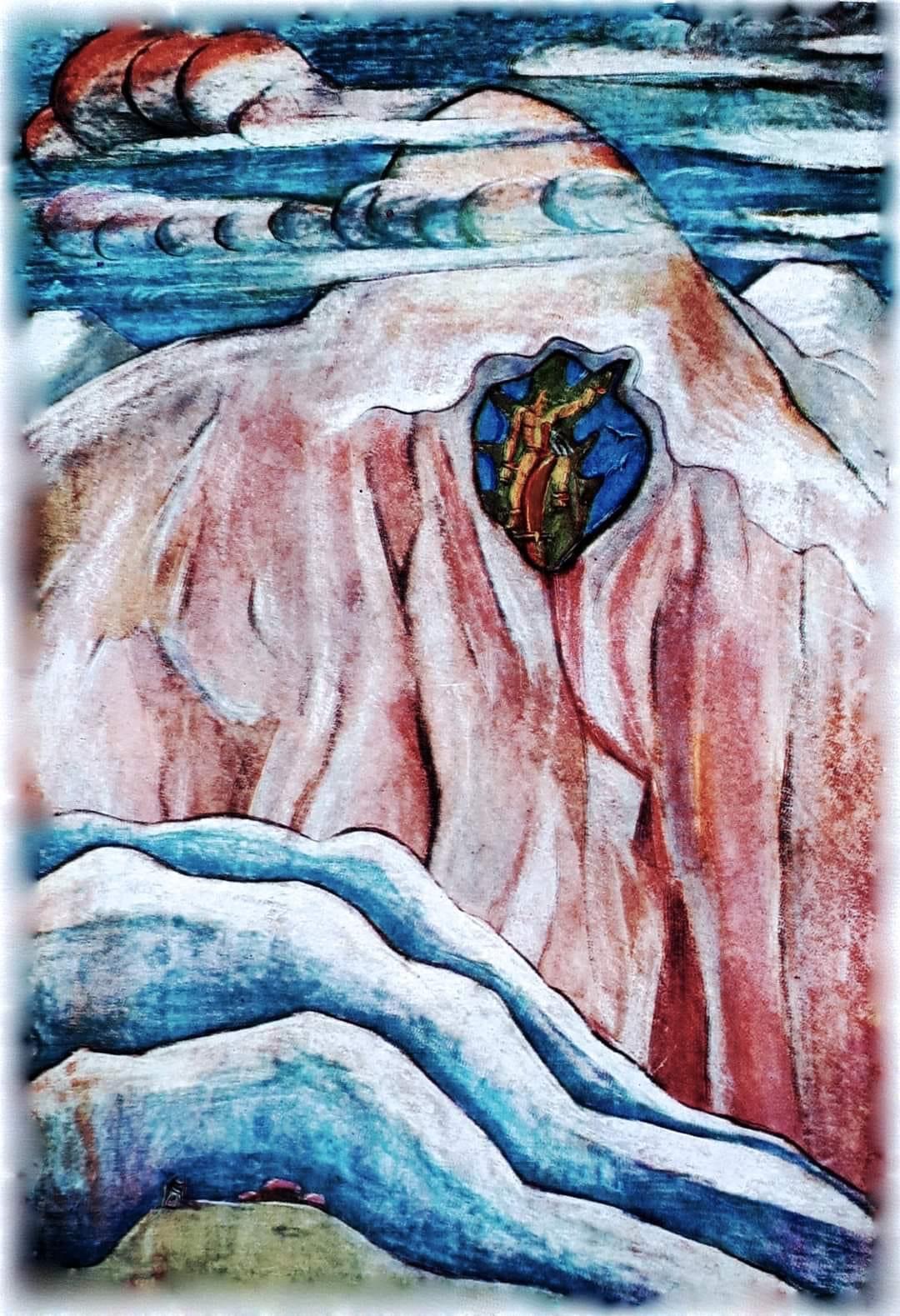

The character at the center of the epic necessarily differs from the rest of the society in terms of origin and power. According to Svan variants, Amirani’s mother is Dali, the goddess of the hunt, and the hero’s father is a hunter who encounters her on an inaccessible cliff. Amirani’s miraculous birth is almost always highlighted: he was taken prematurely from his mother’s womb and finished gestating in the bellies of various animals.

Goddess Dali

In addition to his unusual origin, another attribute that distinguishes Amirani is the strength he possesses from early childhood, which is mentioned in various forms in many versions of the epic. For example, at the age of ten he was already strong enough to fight in a war.

In many stories, Amirani is the godchild of the creator-god, another fact setting him apart from others. The creator often appears to Amirani’s family in the disguise of a pauper. In some texts, angels also appear as godparents. This close relationship with divine figures increases Amirani’s specialness by one or two orders and further separates him from ordinary, human nature. It gives him such powers as the speed of a rolling log, the swiftness of an avalanche, the knee of a wolf (i.e., great stamina), and the power of a twelve-horned water buffalo.

Statue of Amirani

In general, in the epic genre, the special abilities of the main character often come to the fore during the process of finding a bride. Amirani’s bride is a beauty locked in a tower, where she never sees the light of day, who can be carried off only by a remarkable hero with indomitable strength. In most texts, Amirani’s bride is called Qamar, although in a few variants she is referred to by the name of Kamar, or Ketu. In order to get to his bride, Amirani must first defeat her powerful father. According to legend, Qamar’s father can only be defeated if his opponent injures his leg. The beauty herself reveals this big secret to the hero. The victorious Amirani frees Qamar, but the epic does not go into their story any further.

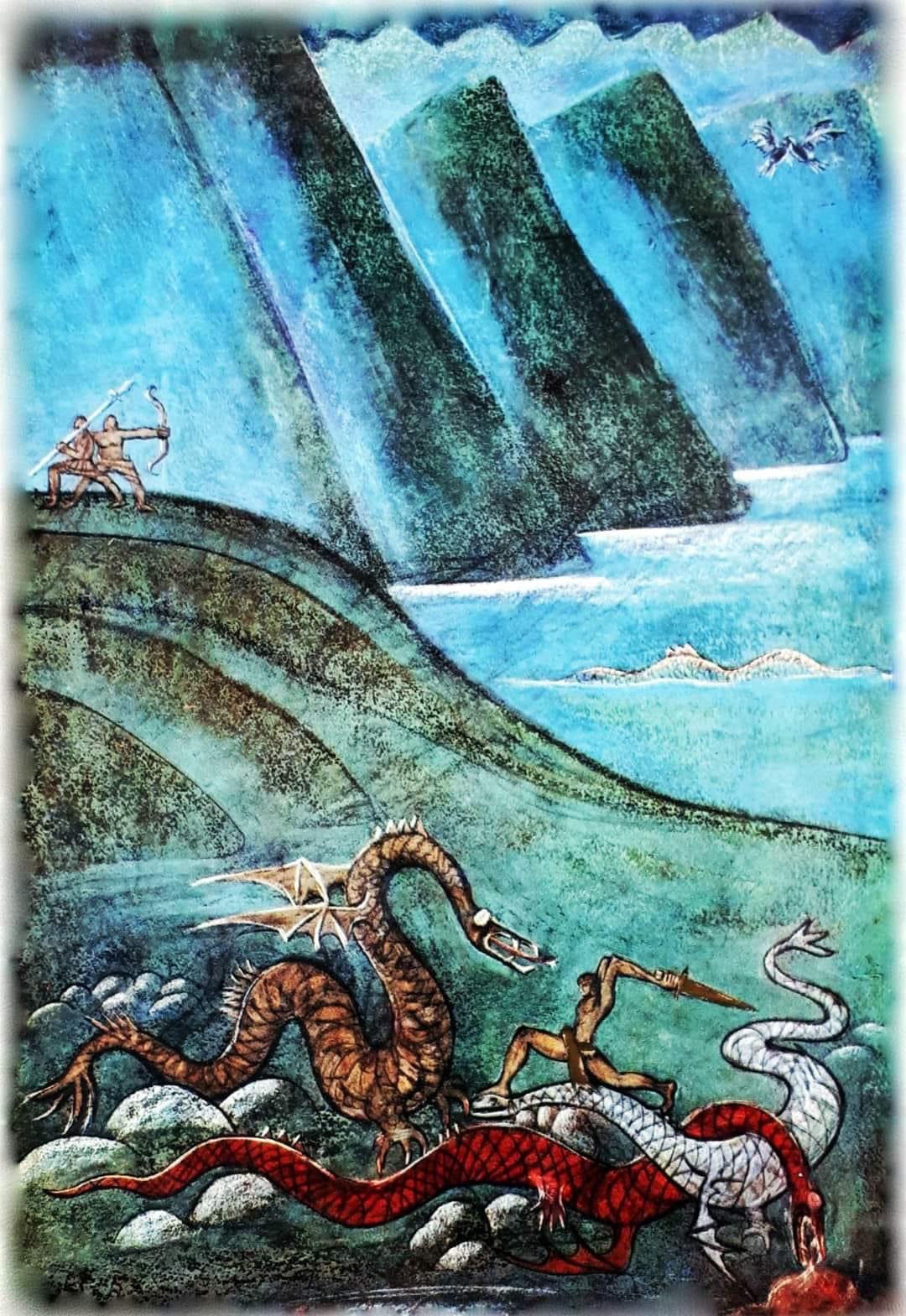

Amirani’s fight against the forces of evil

Another important stage in the life of an epic character is a confrontation with an antagonist, a hostile force. In Amirani’s adventure, this motif manifests through his fights with the devi—a kind of ogre or demon—and with a dragon. In a way, fighting evil is Amirani’s destiny. The Lord specifically selected him, baptized him, and gifted him with a special power, which sets the hero on his mission. In addition, in one of the Georgian versions, it is emphatically stated that Amirani was created by God to kill the devis.

In one variant recorded in Pshavi, the stories of the devi and the dragon are linked. Here Amirani encounters the devi Baqbaq on the road. The hero defeats Baqbaq, yet he does not kill the three worms that emerge from the devi’s head, which later turn into three dragons. Amirani kills two of them, one white and one red, but the black dragon, who breathes fire, swallows Amirani. The hero frees himself with help from Badri and Usup, two characters who appear either as Amirani’s brothers or uncles. Following their instructions, Amirani cuts the dragon’s belly with a knife and is saved.

Struggle against evil

Often in epic narratives, the confrontation with the antagonist is not only a sign of the triumph of good in society, but also a trigger of change in the nature of the hero. The contrast between the antagonist and the epic hero is an expression of the eternal struggle between good and evil. While it displays the character’s powers and his remarkable nature, it also reflects a reality of life—that is, an encounter that transforms a person, gives them experience, wisdom, and the ability to perceive and evaluate life in a new way. In this way, the story of the fight with the dragon signifies rebirth for Amirani.

The rebirth of Amirani

Amirani and Ambri-the-Arab

An interesting episode in Amirani’s adventures is the story of Ambri-the-Arab, featuring the hero’s first defeat. On the road one day, Amirani encounters the dead Ambri, whose leg is hanging from the side of the cart he is lying in. Ambri’s mother asks Amirani to get her dead son’s leg back into the cart. This request, however, turns into an insurmountable obstacle for the hero: try as hard as he might, he cannot move the dead man’s leg. The feeling of failure is further intensified by the mother’s revealing remark, “A dead man has defeated a living one.” This part in the Epic of Amirani is a rare case when the character’s human emotions are openly described. Amirani, shaken by this sudden defeat, “sat down in darkness. Day and night became one for him. He knew neither people nor spirits. No one could come close to him.”[1] The hero, who had been successful everywhere and in everything before this incident, could no longer accept the changed reality and asked God to increase his power. God could not refuse his grieving godchild and gave him another chance. This incident showed Amirani that he could be easily defeated, yet the hero returned to his usual life with renewed strength and decided to fight against the creator himself.

The hero’s hubris and tragedy

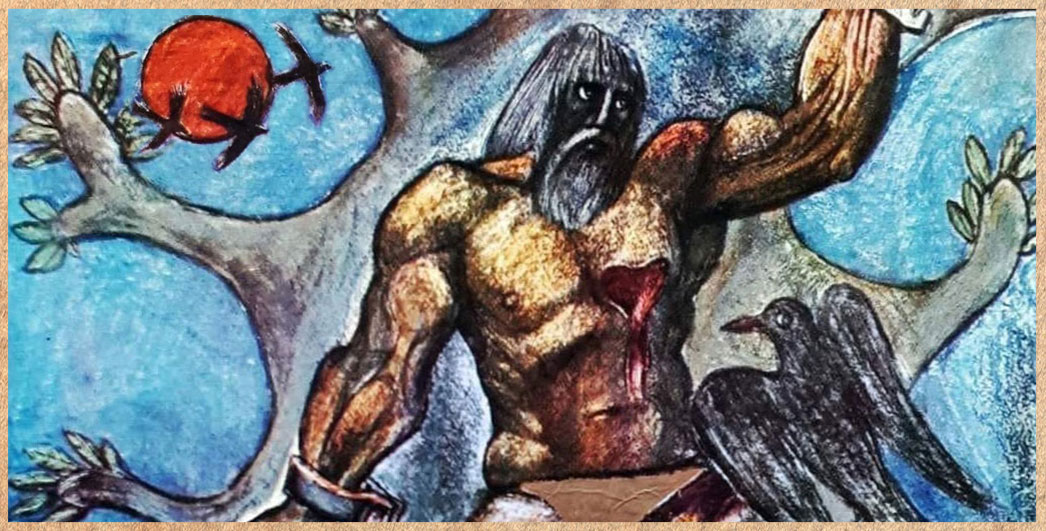

A distinguished origin, triumph over many obstacles, and superior strength often lead epic heroes to hubris and arrogance. The culminating moment in Amirani’s life turned out to be the desire to battle God. While at first he helps to defeat evil, in the end he confronts the greatest good, the Creator. It is likely that the cause of this tragedy is his very uniqueness, his combination of human and divine power. In the Svan variants, as mentioned before, Amirani is the son of the goddess Dali and a mortal hunter. In this hero, baptized by God, there is both a divine and an earthly element, though he does not fully belong to either world. Amirani could easily slay devis or dragons, which pushed him away from his human nature. Nor was it easy to maintain his divine nature in a world full of sin and temptation. This inner struggle resulted in the hero losing his way and committing an unjustified crime. Amirani’s guilt is aggravated by the fact that God (sometimes appearing as Christ) was also Amirani’s godfather, who gifted him with great power and constantly helped him overcome obstacles and sorrows.

When Amirani challenged God to battle, God gave him another chance. For example, in one version of the story, he verbally advises Amirani not to fight him, while in other versions, he shows his superior strength and thus indicates that the hero is doomed to defeat. Nevertheless, blinded by his thirst for glory, Amirani does not realize the impending danger and does not back down. He is chained and punished with eternal trials. There are variants where the hero hints or directly says that he would prefer to die rather than be defeated or bereft of his power. The tragedy of his fate is magnified by the fact that he is sentenced to eternal life but can no longer use his power.

Amirani in Chains

Amirani’s futile attempts to get free are also significant. Amirani has a dog, Goshia, who licks his chains all year long and brings it to the brink of breaking. But the chain becomes whole again just when the punished hero is about to be freed. Amirani constantly tries to move the stake as well. However, his work is unraveled when he shakes his fist at a nearby bird. His fist hits the stake and sinks into the ground again.

The hero is still waiting for his much-longed-for freedom and does not realize that he extends the punishment with his own hand: a fist shaken with fury at the little bird. It could be said that neither the chain will break nor the punishment change, until the hero feels remorse and removes the “shackles” of arrogance.

Works Cited:

[1] Mikheil Chikovani, Mijach’vuli amirani (Amirani Bound) (Tbilisi: Sakhelmts’ipo universit’et’i, 1947), 325. This volume, available for download at the National Parliamentary Library of Georgia, includes a summary in English.

.jpg)