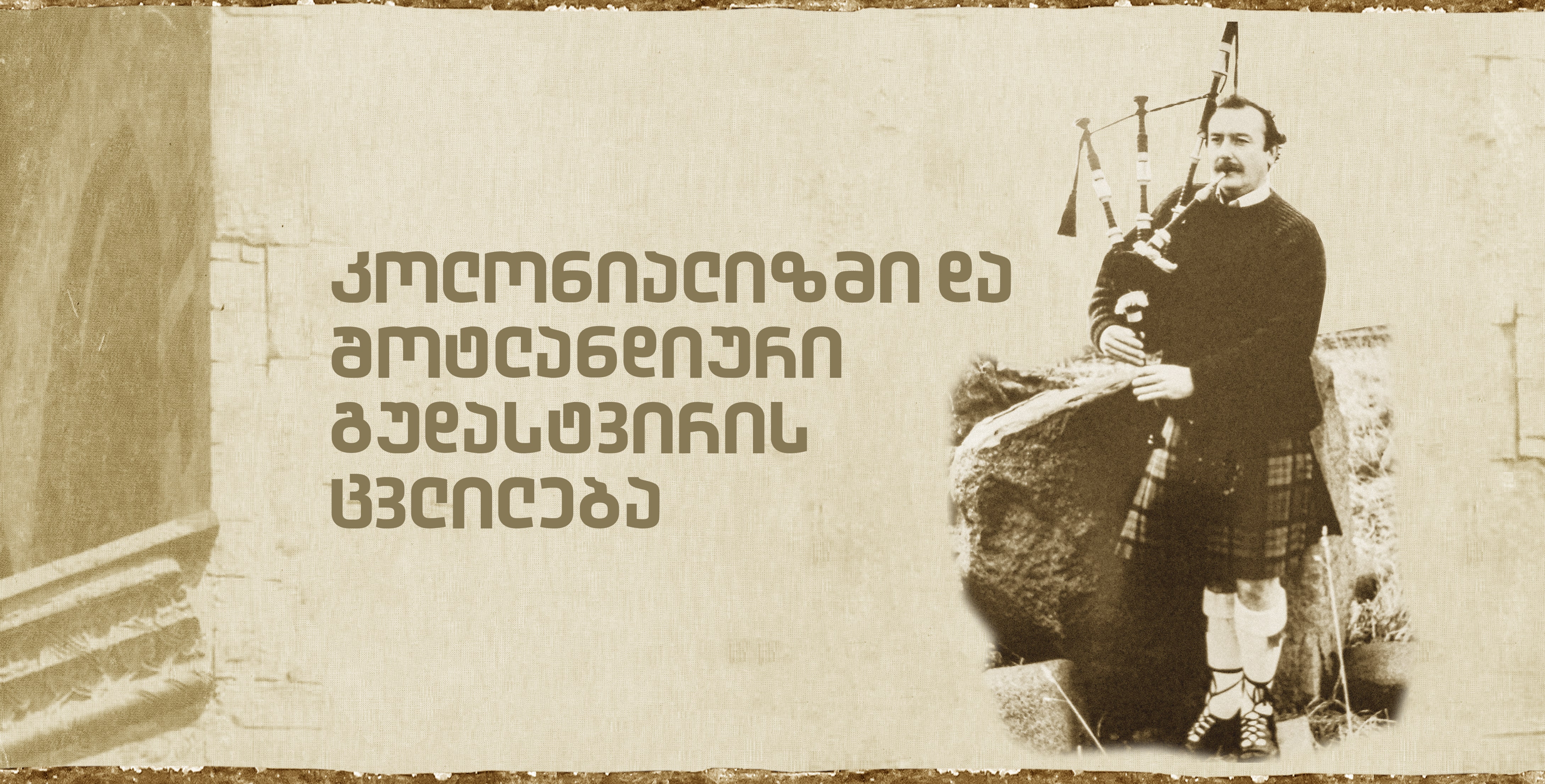

Alilo – The Song that Heralds Christmas

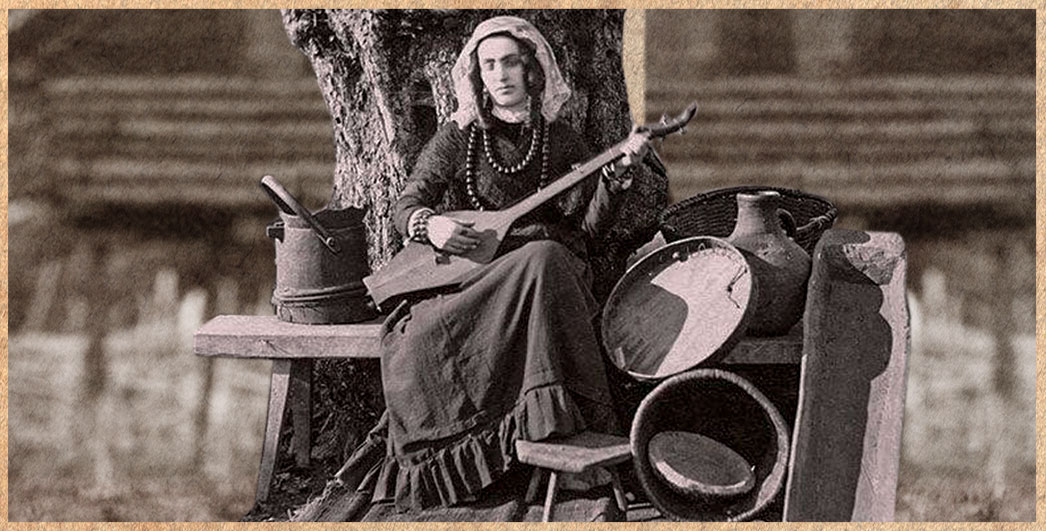

It is a winter evening: the village streets are covered in snow; in the windows you can see the reflection of flames flickering in the fireplace, as the smoky smell fills the air; children are crouching by the fireplace waiting for sweets as the women get ready. At dusk, the song of those walking along fenced-in paths interrupts the reign of silence and fills people’s hearts with hope and joy. This is how I imagine Christmas evening in old, distant Georgia.

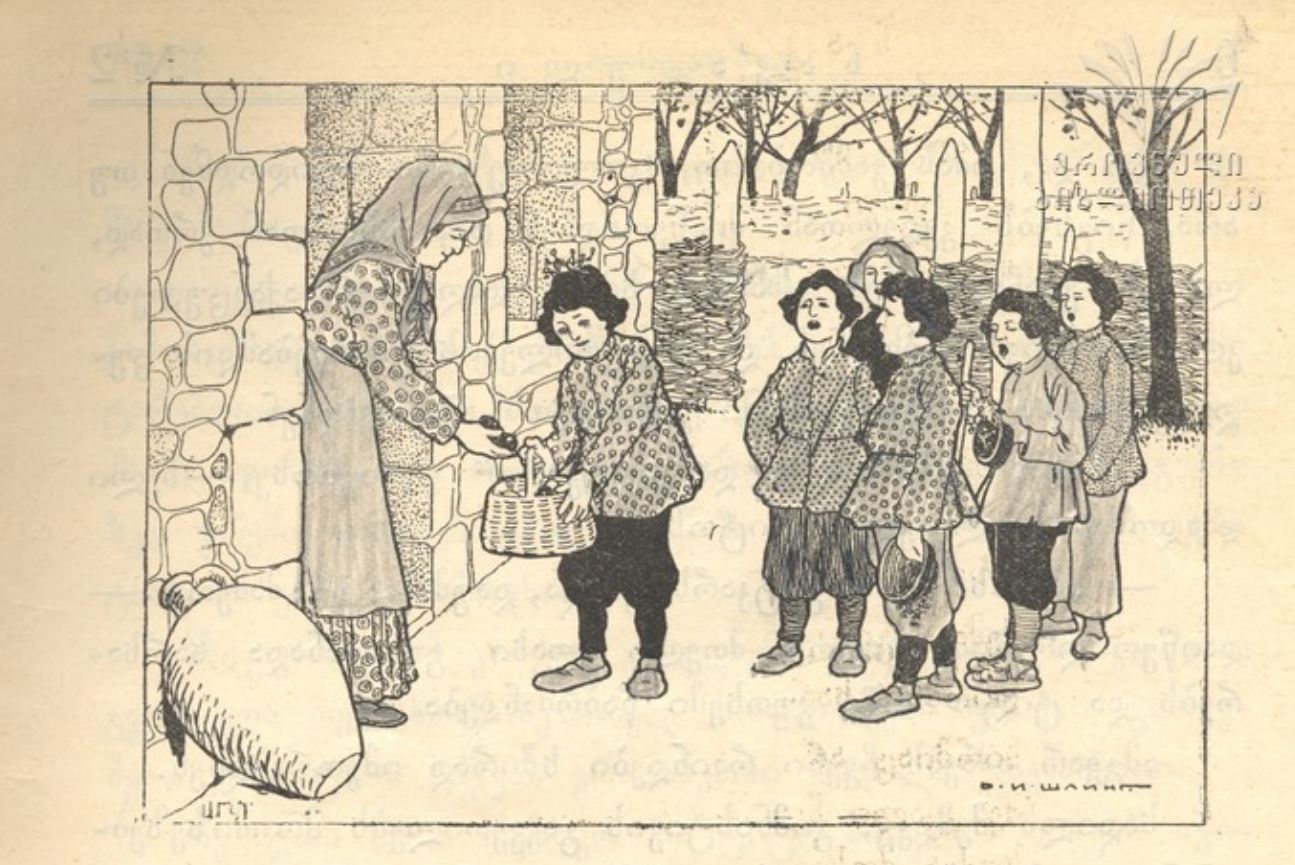

Christmas carols are a common occurrence throughout the Christian world. In our country they are called “alilo”. Alilo is an essential part of the Christmas Eve door-to-door ritual. Someone performing this ritual is called a me-aliloe. These carolers represent the heralds of Christ’s birth. Their arrival is a great honor for the hosts, which is why they greet them happily and give gifts.

All over Georgia, in the highlands and the lowlands, in the east or in the west, they sang all kinds of alilo. Even a village could have its own variant. This is evidenced by the names preserved to this day: Artanuli, Shilduri, Kondoluri, Kvatskhuturi, Tsakhuri, Aketuri, Makvanetiuri and others.[1] The Kakheti region in the east and the Racha, Lechkhumi, Svaneti, Imereti, Samegrelo, and Guria regions in the west are particularly distinguished by the alilo they sing there.

Carolers usually begin their song with an announcement about Christmas: “On the twenty-fifth of this month, Christ was born in Bethlehem.” They also emphasize their own status: “We are not beggars, we are heralds of Christ.” Their Christmas greetings include wishing the hosts material well-being: plenty of bread and wine and ample resources: “May God provide you with as much wine and bread as the Shio wine cellar, and plenty of milk.” [2] They also pray for the ancestors: "Who built this house? Who made its roof from the heart of an oak tree? May the mother of the builder and the soul of the one who roofed it be blessed!”

Christmas songs from every corner of Georgia are unique. For example, in a Kakhetian alilo, two high voices alternate with each other on top of a droning bass. They sing with characteristic melismas and cascading ornamentation. In Gurian, Imeretian, and Megrelian variants, listeners may pick up on a lightness and sharpness of sound, alongside the festive mood. The different kinds of alilo in Rach’a, Lechkhumi, and Svaneti are comparatively weightier and more measured.

No one knows who was the first to have sung this or that alilo, or when these songs appeared, but their musical language and the ritual context of their performance indicate their antiquity. Scholars believe that “alilo” is connected to the word “Hallelujah,” a form of praising God which had come into Christianity from Judaism. While alilo is a song of celebration of the birth of Christ, the corresponding folk rituals retain some echoes of the pre-Christian celebration of the birth of the sun and the victory of light over darkness marked by the winter solstice.

Interesting reports about the tradition of going house to house singing alilo can be found in the magazines and newspapers of previous centuries. In an extensive letter about Georgian traditional music published in 1861 in Tsiskari magazine, the writer and public figure Aleksandre Jambakur-Orbeliani recounts an old story, which, as he notes, happened thirty years earlier. On Christmas Eve, a group of unknown carolers came to sing alilo under the windows of the Orbeliani house. These mealiloeebi turned out to have been from Imereti. Enchanted by the song, the hosts invited them to their home and listened to other Imeretian songs with pleasure (1).

Ensemble „Mtiebi“ on Alilo

People took part in the alilo procession for the purpose of charity as well. For example, one newspaper from December 24, 1897, reports on an ensemble formed especially for the alilo tradition. Interestingly, most of the ensemble members were girls, and their goal was to raise money for the establishment of a women's school in the city (2).

The alilo has also been subject to some negative influences. In 1902, the newspaper Iveria reported that the vocal arrangement of the chants, established since the ancient times, “has been meddled with and changed to a completely different, incomprehensible tuning and language.” The author of the article notes that, in the days before Christmas, children were singing the Christmas troparion in the Russian language, instead of alilo, calling it “Slavic, distorted in a thousand ways, both in terms of content and tuning.” (3) These and similar cases were the logical result of Russia’s annexation of Georgia at the beginning of the nineteenth century, the abolition of the autocephaly of the Georgian Orthodox Church, Russian-language teaching in educational centers, and the suppression of Georgian language and culture. But as it turned out, an even greater trial lay ahead for the alilo tradition. After the establishment of the communist regime in the country, Christmas became a forbidden holiday.

The government tried to suppress religious celebrations through magazines, pamphlets, reports, lectures, and theatrical performances. The anti-religious movement, The Union of Atheists, had come up with a special action plan against Christmas. According to a document preserved in the National Archives of Georgia, the anti-Christmas campaign was to work actively throughout the country from December 15, 1936, to January 20, 1937. The main targets were cultural and educational institutions. We read in the document:

The Department of Education is requested to ensure in every possible way the circulation of the letter of the Committee of Trade Unions on the implementation of the anti-Christmas campaign in schools [...] register all the cells and anti-religious clubs that will be established in schools; tell local drama clubs to prepare and perform anti-religious performances in the days leading up to Christmas; instruct the local cinemas to request anti-religious movies from the film distributors; organize a moving cinema; recruit speakers and send them to the regions. For reports, implement such topics as: Stalinist constitution and religious issues; religion in the service of fascism; the origin of Christianity; and whether or not there was a Christ. (4)

In the Soviet era, the ritual of alilo gradually disappeared from existence, but the song itself was remembered by the people. Despite the bans, you will still find many Christmas songs among the records made by ethnomusicological expeditions in different parts of the country, starting in the 1950s.

From the 1980s, in the wake of the struggle for independence and the process of re-discovering national identity, there was an initiative to return the alilo ritual to existence. This initiative came from the young ethnomusicologist Edisher Garakanidze and the ensemble Mtiebi and gradually gained followers. Ensembles performing traditional Georgian music today try to continue the custom of alilo processions in different villages and cities. On Christmas Eve, you can hear children singing, not always on key, while walking in the alilo procession. For them, this tradition has become a kind of fun game. In the 1990s, I myself took part in this type of alilo. I can say that even in an era of poverty, war, cold and hopelessness, there was plentyof joy and excitement created through the magic of Christmas.

Indeed, Alilooba, the practice of going door to door, offering well wishes, and giving gifts, fills people with positive emotions, even if it is not accompanied by an exceptional rendition of the carols. But it is also a fact that a beautifully performed song adds a special touch to the ritual. It seems that earlier, at weddings, the mealiloe singer was a particularly appreciated member of the wedding party. In a beautiful Christmas story, “Zamtari,”[3] the writer Rezo Inanishvili describes the then still-extant Alilooba of his childhood and tells us how at dusk the first carolers, little boys with big shepherd’s staffs, would appear in the village of Khashmi, in Kakheti. They sang the song breathlessly, packed the gifts received from the hosts into their saddle-bags and proceed to the next house. Then others came, a little older, and they also sang, perhaps more earnestly, but the grandfather, “who was more old-fashioned,” would wait for a different set of mealiloeebi. The expectation was finally fulfilled late at night, when a call was heard at the gates: “Blessings!” It was a choir of a dozen men, helmed by the village priest. Their performance of the “Kakhetian Alilo” and the song “Zamtari” remained an unforgettable memory for the writer. (5)

Andro Simashvili, the song-master and singer from Artana in Kakheti, recalled how, as a small child at the end of the 1920s, he would be woken up by the call of the mealiloeebi and how impressed he was by the Artanuli alilo. As he recalled, “there then came a time when we couldn't include the “Alilo” in the concert program: it was a ritual, that's why. Then we sang about the heroes of the Patriotic War, collectivization, labor. Many traditional songs have been forgotten.” (6) In the 1960s, when some guests gathered at the Simashvilis’ house, they were reminiscing about the past and brought up that almost-forgotten alilo. Andro reconstructed the song and performed it at one of his concerts in 1979. This story of the “Artanuli Alilo” illustrates what happened to alilo in Soviet Georgia .

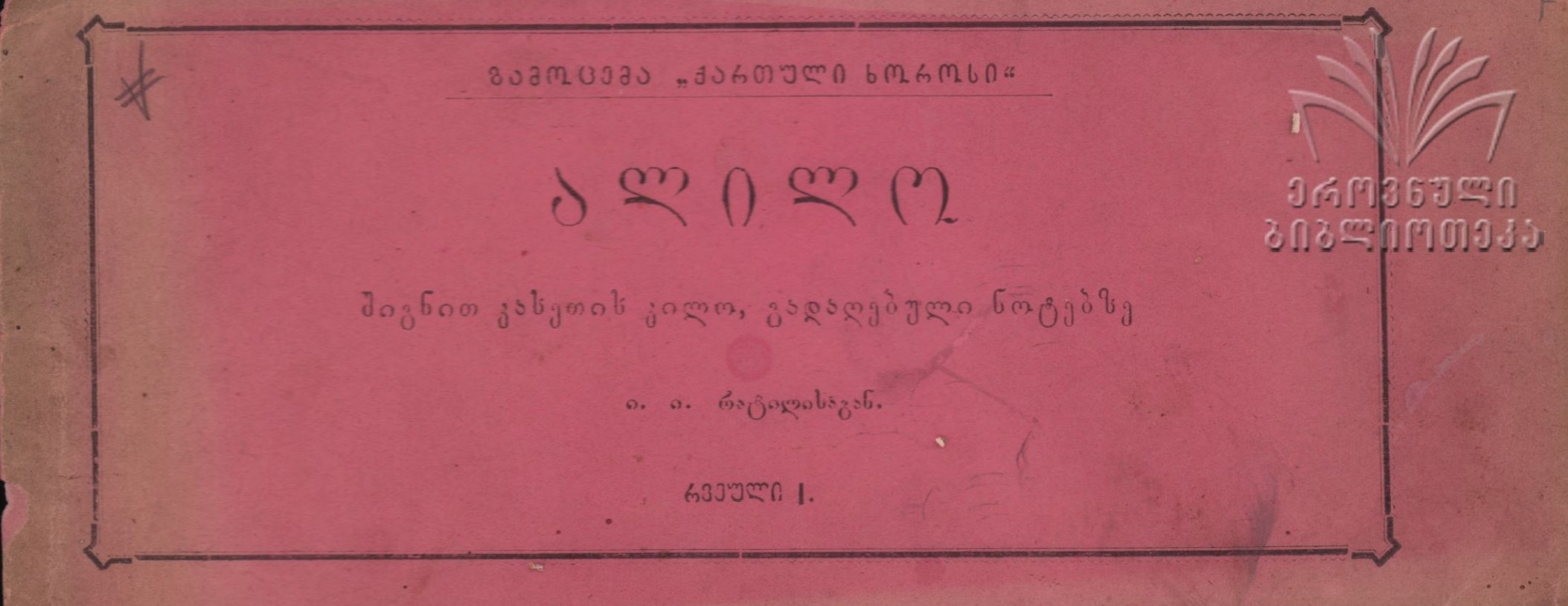

The first notation of an alilo was printed in 1886. The song was arranged in five-line staff notation by the Czech choir master Josef Navrátil (known in Georgian as Ioseb Ratili), leader of the ensemble Georgian Khoro. In 1907 the first sound recording was made by the English Gramophone record company, when, along with other songs by Gigo Erkomaishvili’s choir, the “Gurian Alilo” was recorded.

Alilo from different regions are still heard, studied, and joyfully performed in Georgia after all these years. It seems that it is impossible to erase these from people's memory.

Bibliography

- 1.Jambakur-Orbeliani, Alexander. 1861. “Iverianelebis galoba, simghera da ghighini” (The chanting, singing, and humming of the Iberians). Tsiskari 5, no. 1 (1861):141–160. An abridged English translation appears in Essays on Georgian Ethnomusicology, translated by Ariane Chanturia, 12–16. Tbilisi: International Research Center for Traditional Polyphony, 2005.

- 2.“Alilosatvis shemdgari khoro” (Choir arranged for alilo). Tsnobis purtseli, no. 410 (December 24, 1897): 2.

- 3.Vashadze, B. 1902. “Ekhlandeli Alilo da C’hona” [Present-day alilo and ch’ona]. Iveria, no. 81 (April 18, 1902): 3. https://dspace.nplg.gov.ge/handle/1234/81954

- 4.Central Archive of Recent History of Georgia, fond N1547, case N52.

- 5.Inanishvili, Revaz. “Zamtari” (Winter). https://scroll.ge/14514/revaz-inanishvili-zamthar/

- 6.Kvizhinadze, Marina. 2015. Andro Simashvili (Tbilisi: Ustari), 37–40.

[1] All these names reference specific villages in Georgia. For example, Aketuri = “from the village Aketi.”

[2] The Shio wine cellar is used here as a shorthand for wealth and abundance. The saying comes from the wine cellar of the Shio monastery, near the city of Mtskheta, where a particularly generous monk would provide wine for the worshippers. According to legend, the kvevri (clay amphoras used in traditional Georgian wine-making) which were empty by the end of the day, would be full the next morning.

[3] Zamtari means “winter.”

%20%E1%83%97%E1%83%94%E1%83%9D%E1%83%9C%E1%83%90%20%E1%83%A0%E1%83%A3%E1%83%AE%E1%83%90%E1%83%AB%E1%83%94%20-%20%E1%83%A1%E1%83%90%E1%83%A0%E1%83%94%E1%83%93%E1%83%90%E1%83%A5%E1%83%AA%E1%83%98%E1%83%9D%20%E1%83%A1%E1%83%90%E1%83%91%E1%83%AD%E1%83%9D%E1%83%A1%20%E1%83%AC%E1%83%94%E1%83%95%E1%83%A0%E1%83%98-min.jpg)