Ch’iboni: The Bagpipes from Ach’ara

Introduction

On November 5, 1916, the newspaper Sakartvelo informed its readers about the composer Kote Potskhverashvili’s recordings of Ach’aran folklore. The article, written by ethnographer Apollon Tsuladze, includes a noteworthy account of a meeting that took place in Guria, at the Bakhmaro resort, between Potskhverashvili and a group of Ach’aran mekhorumeebi, that is, performers of the khorumi, a traditional folk dance accompanied by bagpipes and drums. These performers were “walking in groups with ch’imoni and davli, attracting attention with their dancing and

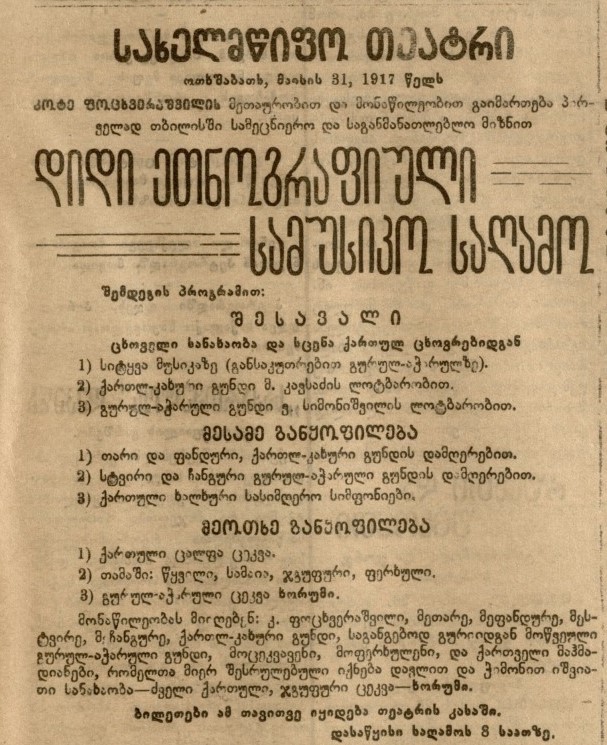

singing in honor of the Muslim holiday of Ramadan.”[i] A year later, the same newspaper announced a big ethnographic evening to be held in Tbilisi on the initiative of Potskhverashvili, an event that promised to end with “a rare sight—the khorumi, performed by Georgian Muslims accompanied by ch’iboni and doli.”[ii]

Front page of the Sakartvelo newspaper, May 30, 1917, advertising an ethnographic concert.

It might seem strange at first that one of the most popular dances nowadays was considered a “rare sight” for the general public. Yet the beginning of the twentieth century was when the first attempts were made to gather and research Georgian musical folklore—truly, an era of discoveries! In the case of Ach’ara, historical context adds another layer. Ach’ara and several other regions of Georgia, which had been part of the Ottoman Empire for three centuries, were returned to Georgia in 1878.[iii] It was then that the long process of rediscovering and reviving Georgian culture in Ach’ara began, entailing the contributions of many artists, including Kote Potskhverashvili, considered the first researcher of traditional music in this area..

Ch’iboni: terminology, main characteristics, and previous scholarship

The ch’iboni is the Ach’aran variety of the bagpipes (also known as gudast’viri in Georgian),a wind instrument common in many regions of the world. In the Ach’aran dialect, ch’ibona is the term for a reed whistle, and it seems like that the instrument gets its name from this word.[iv] In Ach’ara, the player of the ch’iboni is called mech’ibone (or mech’ibne), and the verb for playing is dach’iboneba. Ach’ara is not the only region of Georgia where bagpipes are widespread. The tradition of bagpipe-playing has been preserved in Rach’a to this day. This instrument has also been recorded in Kartli, Pshavi and Meskheti-Javakheti. It can also be found in the historical regions of Georgia which are part of modern-day Turkey: Tao, Shavsheti, and Lazeti.

Kote Potskhverashvili was the first to present the Ach’aran bagpipe to the general public although this instrument was noticed even earlier by scholars like Tedo Sakhokia and Niko Marr, who traveled to the region in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[v] Their French contemporary, researcher Jules Mourier, also mentions the Ach’aran bagpipes in his notes.[vi] Ch’imon as a term for bagpipes was defined by the lexicographer Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani, who was active in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.[vii] In the twentieth century, bagpipes became an object of academic research by historians, ethnographers, and ethnomusicologists. Aleksandre Mskhaladze dedicated a monograph specificially to the Ach’aran ch’iboni.[viii]

The physical structure of the ch’iboni is rather complex and includes many details. One of the instrument’s main parts, the bag (guda), is made from goatskin, and the pipes or chanters (st’viri, from the word for “whistling”) are made from reeds. In order for the instrument to make a sound, a performer first inflates the bag, filling it with air, and then plays melodies by squeezing the bag under their arm and moving their fingers on the holes cut into the chanters. On YouTube, you can see the process of making the ch’iboni, from an episode of the television program “Ethnographic Sketches” (please note: this video contains images of a goat being killed for its skin)

The ch’iboni as part of traditional Ach’aran life

The ch’iboni is primarily played to accompany dancing. Different variants of such examples of Ach’aran choreography as the khorumi and gandagana are often performed on it. Due to its connection with dance, you will also often the ch’iboni in a duet with the drum known as the doli. The ch’iboni, which players often kept on hand at all times, was an integral part of celebratory gatherings. The mech’iboneebi were always invited to weddings and baptisms. According to Mskhaladze, at weddings the ch’iboni would play the bride’s parents’ farewell tune, as well as dance songs, and on the second morning of the wedding, the sound of the ch’iboni would wake up the still-sleeping bride and groom by imitating a rooster's crowing.[ix]

%20%E1%83%A3%E1%83%AA%E1%83%9C%E1%83%9D%E1%83%91%E1%83%98%20%E1%83%AB%E1%83%95%E1%83%94%E1%83%9A%E1%83%98%20%E1%83%90%E1%83%AD%E1%83%90%E1%83%A0%E1%83%90%2C%20%E1%83%92%E1%83%95-%2089%20(1).jpg)

Khorumi dance, 1937. (Khariton Akhvlediani State Museum of Ach’ara)

In the mountains of Ach’ara, no shuamtoba—a celebration connected to the traditions of seasonal farming and cattle breeding—would be complete without the ch’iboni. This instrument complemented the folk theater ritual known as Padik’o, in which the participants, accompanied by music and dance, would try to capture and kidnap the main character, named Padiko, who was a man disguised as a woman. [x] The ch’iboni was also employed in the work process. According to an eighty-year-old storyteller named Qember Dolidze, cited by Aleksandre Mskhaladze in the 1960s, a mech’ibone and medole (doli-player) would take part in the nadi—a period of collective work on farms in Georgia—playing as the farmers worked.[xi] According to another story recounted by Mskhaladze, when the wood was brought out of the forest to the sawmill, a ch’iboni player seated on top of the logs would play rhythmic melodies.It is relatively rare to hear the ch’iboni as accompaniment for vocal performance. When it does occur, the ch’iboni-player sings and dances while playing or accompanies someone else's singing. This audio clip is one of the rare examples of singing with the ch’iboni.

Atlatita (with chiboni and doli. Ensemble Chvana, 2016)

First recordings of the ch’iboni and its life on stage

The history of sound recordings of the ch’iboni begins in 1932, when the composer and folk music collector Shalva Mshvelidze recorded the famous Ach’aran mech’ibone Edehem Surmanidze (nicknamed Kochakhela) on the phonograph.[xii] In the 1930s, the instrument seems to have been quite popular, as evidenced by its appearance at such important events as the Transcaucasian People’s Olympiad (1934) and the Dekada (ten-day festival) of Georgian Art in Moscow (1937).

While in the 1930s the ch’iboni would usually appear either alone or with a doli, accompanying village dancers in something like an authentic context, its role changed in later decades, and the instrument became a part of the large choreographic ensembles characteristic of the Soviet period. This tradition continues today, and the ch’iboni is a member of the growing and increasingly diverse instrumental section of choreographic ensembles. We often encounter it as well in modern ethno-jazz bands.

The Shin. Cheaps On The Water

Along with interesting stage experiences from the beginning of the last century to the present day, the ch’iboni is still rooted in Ach’aran folklore and continues to function in its natural environment to this day.

A continuous, centuries-old tradition

As I mentioned earlier, Edehem Surmanidze (1861-1955) was the first among those performers whose recordings have been preserved by sound archives. Older musicians still talk about his unique playing style and diverse repertoire. It is said that this great mech’ibone was often invited by the Khimshiashvili Beys of Ach’ara to their summer residence in Kochakhi (Mtisubani, formerly Mumsui, a village in the Khulo municipality), from which the nickname “Kochakhela” comes.[xiii]

Edehem Surmanidze was the most famous, but not the only, mech’ibone of his time. For example, in 1949, at the Sixth Olympiad of folk creativity in Tbilisi, Kochakhela was decorated by another famous ch’iboni-player from his region, Rostom Jimsheradze (1900-1967). The list of the musicians drawn up by Mskhaladze in 1964 includes sixty-five masters.[xiv] From the second half of the twentieth century to the present day, many ch’iboni-players have been recorded from Ach’ara.

The master-apprentice tradition for this instrument is known as mech’iboneba, and it is passed down from generation to generation. One is considered to be a real musician when, along with playing, one can also make and tune the instrument and share this knowledge and experience with students. Like Kochakhela, Vaso Iremadze (1941-2003) is considered one of the outstanding ch’iboni-player in Ach’ara. His students remember this master with love and respect and continue his tradition. Iremadze's talent and skillful performance shine through in the following clip, recorded in 2000:

In 1969, Aleksandre Mskhaladze ended his monograph on the ch’iboni with the pessimistic sentiment that the instrument “is being forgotten and belongs in the museum.”[xv] The ch’iboni tradition has indeed weakened over the last fifty years, but it has not been lost. It is still part of Ach’aran folk practices, and its musicians present their art not only in Georgia but also abroad.

(Photo) Murad Tavartkiladze and Temur Ardzenadze at the National Festival of Georgian Folklore, 2022. (Archive of the State Folklore Centre)

Along with Ach’ara, the original bagpiping tradition is still preserved in Rach’a. However, bagpipes of this area differ from the Ach’aran ch’iboni, not only in structure and sound, but also in function and, therefore, in repertoire. These details of regional difference warrant a separate article, which we will prepare in the future.

[i] Apollon Tsuladze, “Ach’aruli sasimghero leksebi da b. k. potskhverashvili” (Ach’aran song poems and Mr. K. Potskhverashvili,” Sakartvelo, November 5, 1916 (no. 248), p. 2. Ch’imoni and davli are alternative terms for ch’iboni and doli. For more information, search the terms ჭიმონი and დავლი in the Georgian Explanatory Dictionary: https://www.ena.ge/explanatory-online.

[ii] Sakartvelo, May 30, 1917 (no. 114), p.1.

[iii]After the Russo-Turkish war, according to the Treaty of Berlin, certain territories of the Ottoman Empire, including historical parts of Georgia, were transferred to the Russian Empire..

[iv] Aleksandre Ghlonti, Kartul k’ilo-tkmata sit’qvis k’ona [Dictionary of Georgian dialect terms] (Tbilisi: Ganatleba, 1984), 721. Online version: http://www.nplg.gov.ge/gwdict/index.php?a=index&d=56.

[v]Around the turn of the twentieth century, Tedo Sakhokia, a traveler to Ach’ara, noted in his diary: “The only musical instrument that expresses the local spirit is the ch’imon (similar to the Rach’an sazandri).” Tedo Sakhokia, Mogzaurobebi: guria, ach’ara, samurzaqano, apkhazeti [Travels: Guria, Ach’ara, Samurzaqano, Abkhazia] (Batumi: Sabch’ota Ach’ara, 1985), 237). In the diaries for Niko Marr’s 1904 trip to Shavsheti and Klarjeti, we read: “On the feast-day (Friday), the local Muslims gather near the temple to play or gossip (for fun). Once, during my stay here, young men came to the celebration with bagpipes: tulum or, in Georgian, ch’ibo, as it is called in Imerkhevi. But here, too, the Georgian element is evoked in the names of different parts of this instrument, although Georgian is not spoken in the village.” Niko Marr, Shavshetsa da k’larjetshi mogzaurobis dghiurebi [Travel diaries in Shavsheti and Klarjeti], edited by Mamia Paghava (Batumi: Shota Rustaveli State University, 2012), 140.

[vi] Jules Mourier, Batoum et le bassin de Tchorok (Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1887), 41.

[vii] Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani, Leksik’oni kartuli [Dictionary of Georgian], vol. 2 (Tbilisi: Merani, 1993), 402.

[viii] Aleksandre Mskhaladze,) Kartuli khalkhuri sak’ravieri musik’is ist’oriidan: ch’ibo da misi t’raditsia ach’arashi [From the history of Georgian folk instrument music: the ch’iboni and its tradition in Ach’ara](Tbilisi: Metsniereba, 1969).

[ix] Mskhaladze, Kartuli khalkhuri sak’ravieri, 37–38.

[x]According to researchers, the Padik’o spectacle in Ach’ara is an echo of ancient mysteries dedicated to a fertility deity. Later, it took the form of wedding entertainment. In addition to weddings, Padik’o was also performed in the shuamtoba festival in the highlands of Ach’ara, which in turn was a religious celebration held for economic prosperity, fertility, abundance, and childbearing. Today, Padik’o is a humorous dance that is accompanied by instruments and singing. See Aleksandre Mskhaladze, Ach’aris saojakho-sats’eschveulebo p’oezia (Household and calendar poetry of Ach’ara) (Batumi: Sabch’ota Ach’ara, 1969) , 93–98; Roin Metreveli, ed. Kartveli khalkhis etnologiuri leksik’oni: Ach’ara (Ethnological dictionary of the Georgian people: Ach’ara) (Tbilisi: Samshoblo, 2018), 431–32.

[xi] Mskhaladze, Kartuli khalkhuri sak’ravieri, 30.

[xii]See the audio collection Echoes from the Past: Georgian Folk Music from Phonograph Wax cylinders, vol. 2 (Tbilisi: Tbilisi State Conservatoire et al., 2007). Shalva Mshvelidze’s 1932 collection appears on CD 5.

[xiii] Nodar Surmanidze and Nikoloz Dumbadze, “Kochakhelas sakhelisa da sadaurobis dazust’ebisatvis” (Determining the name and ancestry of Kochakhela), Chorokhi, no. 6 (2018): 117.

[xiv]Mskhaladze, Kartuli khalkhuri sak’ravieri, 44–45.

[xv] Mskhaladze, Kartuli khalkhuri sak’ravieri, 43.

%20%E1%83%97%E1%83%94%E1%83%9D%E1%83%9C%E1%83%90%20%E1%83%A0%E1%83%A3%E1%83%AE%E1%83%90%E1%83%AB%E1%83%94%20-%20%E1%83%A1%E1%83%90%E1%83%A0%E1%83%94%E1%83%93%E1%83%90%E1%83%A5%E1%83%AA%E1%83%98%E1%83%9D%20%E1%83%A1%E1%83%90%E1%83%91%E1%83%AD%E1%83%9D%E1%83%A1%20%E1%83%AC%E1%83%94%E1%83%95%E1%83%A0%E1%83%98-min.jpg)