Georgian Chanting in Soviet Georgia

The opportunity to establish statehood, democracy, unrestricted education and creativity, personal freedom, integration with Europe, and development—which emerged after Georgia's independence in 1918—was unfortunately interrupted in less than three years and terminated for many decades due to the occupation and annexation of Georgia by Bolshevik Russia. The history of the country's Sovietisation, marked by ideological pressure, terror, and repression, represents one of the most challenging periods for our nation, with effects still evident in various aspects of life.

Soviet ideology, while distorting and degrading people's social, economic, and psychological states, also moulded and shaped the so-called "Homo Sovieticus" under the regime's pressure. This profoundly influenced the country's cultural life in various spheres, with traditional Georgian music being no exception. The Communist Party's directive to modify, adapt, and exploit the rich tradition of folk singing for Soviet ideological purposes was quickly enforced. Under the dictatorial and repressive regime, many of the finest practitioners of the living folk singing tradition were compelled to incorporate texts praising communism and its leaders into songs, form mass choirs, and participate in Union Olympiads designed to propagate communist ideology.

Despite these challenges, folk songs continued to survive in the Soviet reality, which cannot be said for one of the most valuable domains of Georgian traditional music—chanting. Amidst the country's aggressive atheism and the prohibition of chanting, its condition became dire, teetering on the brink of complete disappearance. The roots of this crisis trace back to the 19th century, following Georgia's annexation and the abolition of its church's autocephaly, when Georgian culture, including its chanting tradition, became the target of persecution. The Bolshevik regime drove it to the edge of extinction. The words of Kalsitrate Tsintsadze from the late 1920s illustrate the state of Georgian chanting: "Since 1927, there has been no well-disposed choir in the church; the chanters are assisted by lay believers who are 'knowledgeable' about chanting.”[1]

The repressions of the 1930s, which claimed the lives of numerous clergy and laypeople skilled in chanting, further reduced the number of bearers of the ancient tradition. In such circumstances, the presence of individuals who inherited Georgian chanting culture and were raised within its living tradition held profound historical significance.

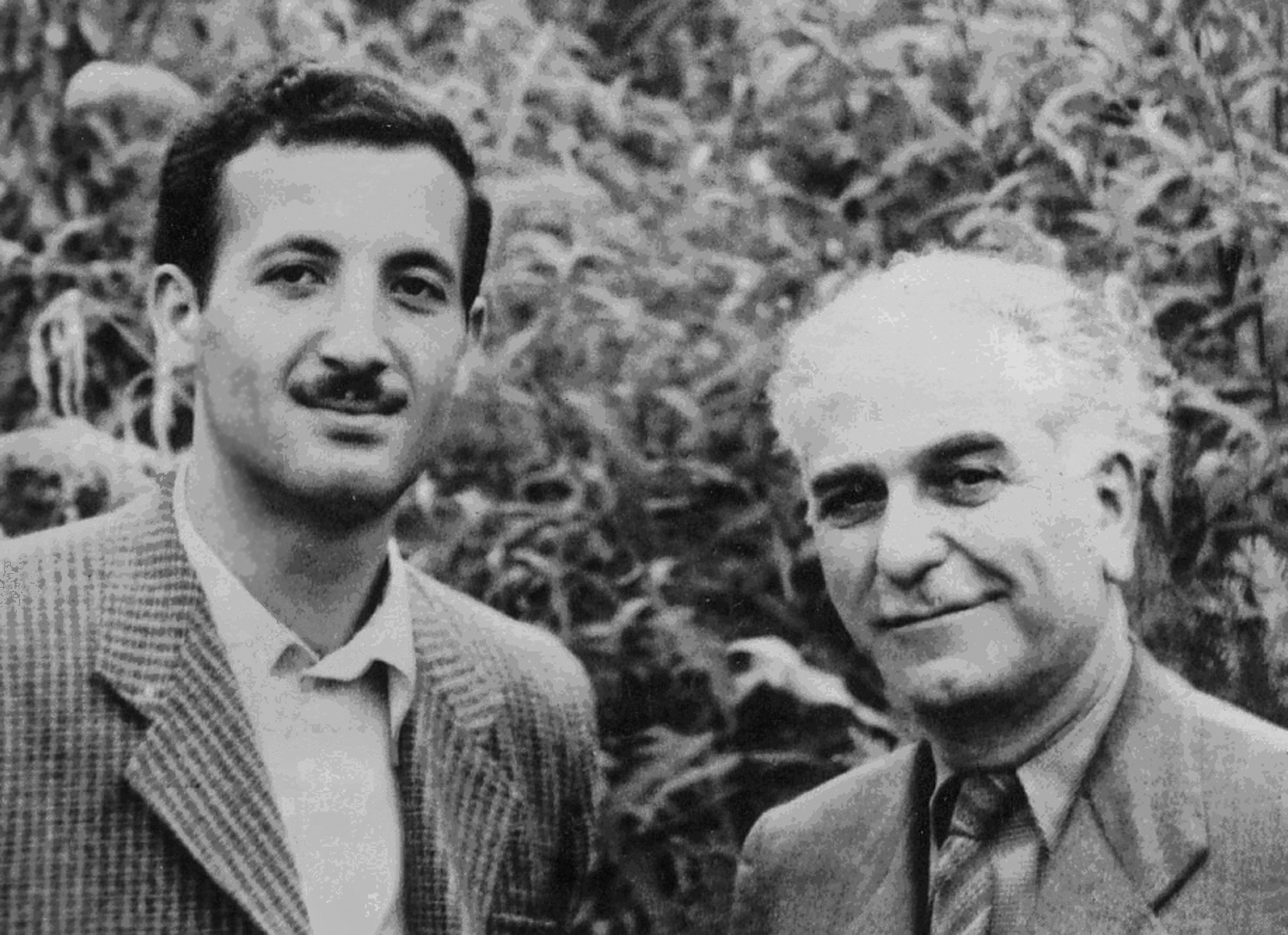

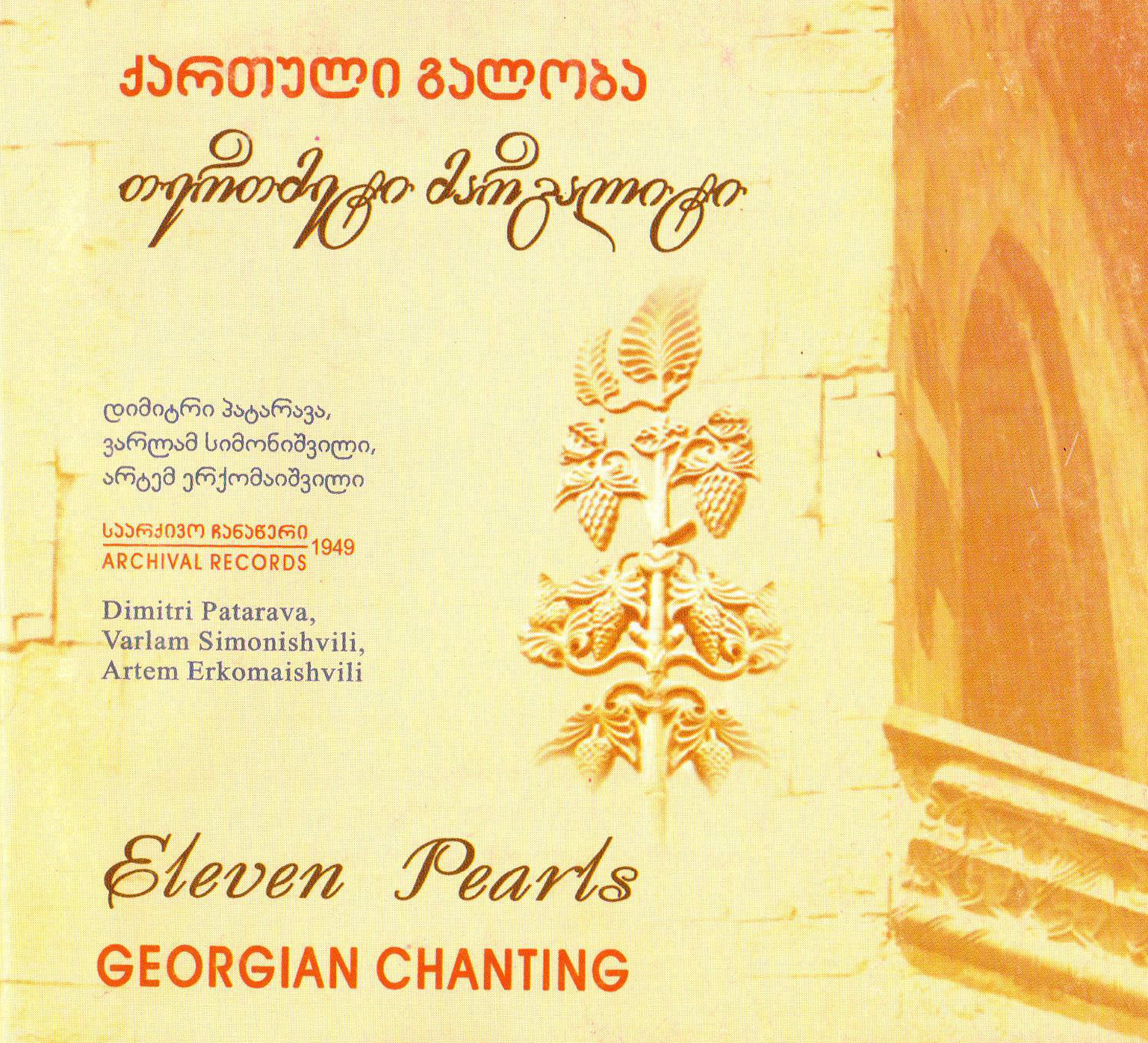

After World War II, the state's rigid stance towards religion (including Christianity) softened to some extent, leading to a relatively more tolerant attitude. This allowed for occasional bold attempts to search for and document chants. Notably, Vladimer Akhobadze, a lecturer in the Department of Folklore at the Tbilisi State Conservatory, took a courageous step in this direction. During a 1949 expedition to Ozurgeti in Guria, which he led, Akhobadze recorded 11 hymns from the last masters of chanting: Dimitri Patarava, Artem Erkomaishvili, and Varlam Simonishvili.[2]

|

|

These unique recordings are among the earliest audio samples of Georgian chanting, following two hymns recorded in 1909 by the "Gramophone" troupe from Gurian singers[3] and several hymns recorded by Shalva Aslanishvili in Racha in 1928.[4]

Recordings of hymns also appear in other expedition materials. The regions where they were preserved among the people were predominantly Guria, Imereti, Kakheti, and, to some extent, Svaneti. Notably, the texts of some hymns—especially in materials recorded in Guria—frequently show changes that obscure, conceal, or even erase their ecclesiastical (religious) purpose. One example is the hymn to John the Baptist, “Mertskhalo, Mshveniero” (“Swallow, Beautiful One”), where, in the last two verses, the original words—“Christ’s precursor, the one created in the wilderness/desert, make me fruitful of the good ones”—are replaced with: “Herald of life, the beauty of nature, rejoice and chirp, my vivacious one!”[5] This alteration transforms the hymn to John the Baptist into a song about a swallow.[6]

A similar transformation is evident in an audio recording of St. Nino’s Kontakion, performed by Artem Erkomaishvili alongside his grandson, Anzor Erkomaishvili, and Badri Toidze. In this recording, the original opening words, “Apostle, distinguished by Christ,” are changed to “Apostle, distinguished by the people” (likely recorded in 1964–65).

Members of the generation who had experienced repression and still retained knowledge of Georgian chant often harbored fear and dis, trust toward the Soviet authorities. This sentiment is vividly illustrated in an audio recording preserved in the National Archive of Georgia. Specifically, on one tape, folklorist Kakhi Rosebashvili, while preparing to record hymns from Nestor Jibladze, states: "Batumi city, August 10, 1967. We are recording ecclesiastical hymns from Nestor Jibladze." At this point, Nestor Jibladze interrupts the recording with a comment. When the recorder is turned back on, Kakhi Rosebashvili can be heard reassuring him: "Don’t be afraid; they won’t arrest us!" This exchange reveals that 72-year-old Nestor Jibladze feared Soviet censorship while recording the hymns.[7]

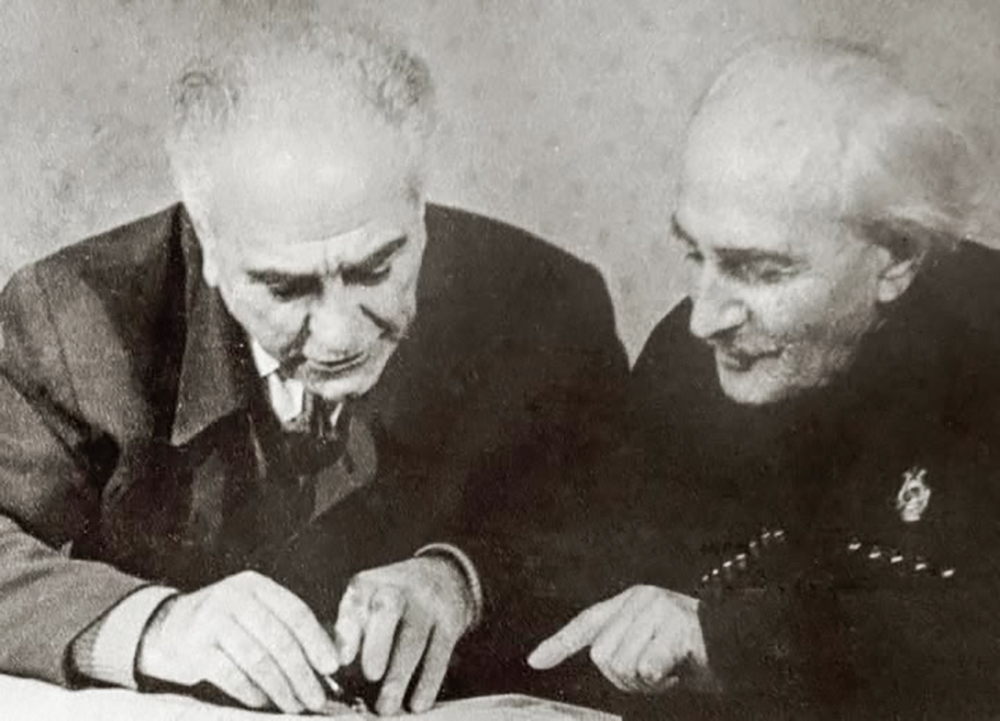

Considering this, it is even more commendable that in 1966, under the initiative of Grigol Chkhikvadze, head of the Department of Musical Folklore at the Tbilisi State Conservatory, and scholar Kakhi Rosebashvili from the same department, permission was granted to invite the last master of the chant tradition, Artem Erkomaishvili, to record hymns at the Conservatory. It must be noted that these recordings by the 79-year-old chanter preserved and safeguarded for future generations a unique collection of 107 hymns, representing one of the chant traditions—the Shemokmedi school of Georgian chanting.[8] Additionally, the valuable audio recordings of several hymns passed down by Artem and his brothers, Ladiko and Anania Erkomaishvili, such as “Siq’varulman Mogiq’vana” (Love Has Brought You) and “Shen Khar Venakhi” (You Are a Vineyard), deserve mention.

|

Left to right: Kakhi Rosebashvili and Grigol Chkhikvadze |

Left to right: Grigol Chkhikvadze and Artem Erkomaishvili

|

It should be noted that at the end of the 1950s and throughout the 1960s, a certain dualism can be observed in the attitude toward the field of chanting. As demonstrated by the examples above, there was still caution regarding ideological censorship; however, at the same time, interest in this aspect of traditional Georgian music undoubtedly grew. In this regard, the scholarly study of Georgian chant became relatively more active. Attention to ancient hymnographic manuscripts, paleographical monuments, and particularly the musicological aspects of neumatic musical notation, increased during this period.[9] Despite this, the number of scholars studying chant and its musical nature remained small.

In this context, the publication of the Georgian hymn collection by Kakhi Rosebashvili in 1968 was historically significant. This collection includes the notated transcription of selected hymns passed down by Artem Erkomashvili.[10] It should be noted that this publication was the first instance of hymn publication across the Soviet Union, setting a precedent in this regard. This small-circulation publication seemingly did not attract the attention of Soviet censorship. The same cannot be said for the first public performance of hymns, which took place in 1963 in the small hall of the Tbilisi State Conservatoire, performed by the ensemble “Gordela.” The censorship certainly took notice of this highly publicised concert, but it seems that an exception was made, likely due to the growing public interest in Georgian chant and its recognition as a cultural treasure. Following "Gordela," hymns became part of the concert repertoire of the ensemble "Rustavi," and later, they were also recorded and released on gramophone records.

During this period, both within Georgia and beyond its borders, the hymn "Shen Khari Venakhi" became a symbol of Georgian chant, gaining widespread recognition and acclaim from the public. Since this beautiful iambic hymn, dedicated to the Virgin Mary by King King Demetre I (12th century), metaphorically presents the Virgin Mary as a vineyard, it seems that Soviet censorship interpreted the text literally, considering it a hymn (song) dedicated to a vineyard. Therefore, its performance and publication under this title encountered no obstacles. This is confirmed by the 1968 vinyl record collection Georgia in Folk Songs, compiled by Pavle Khuchua, which included this hymn, performed by the State Choir of Georgia and conducted by Jansugh Kakhidze, alongside other Georgian folk songs.[11]

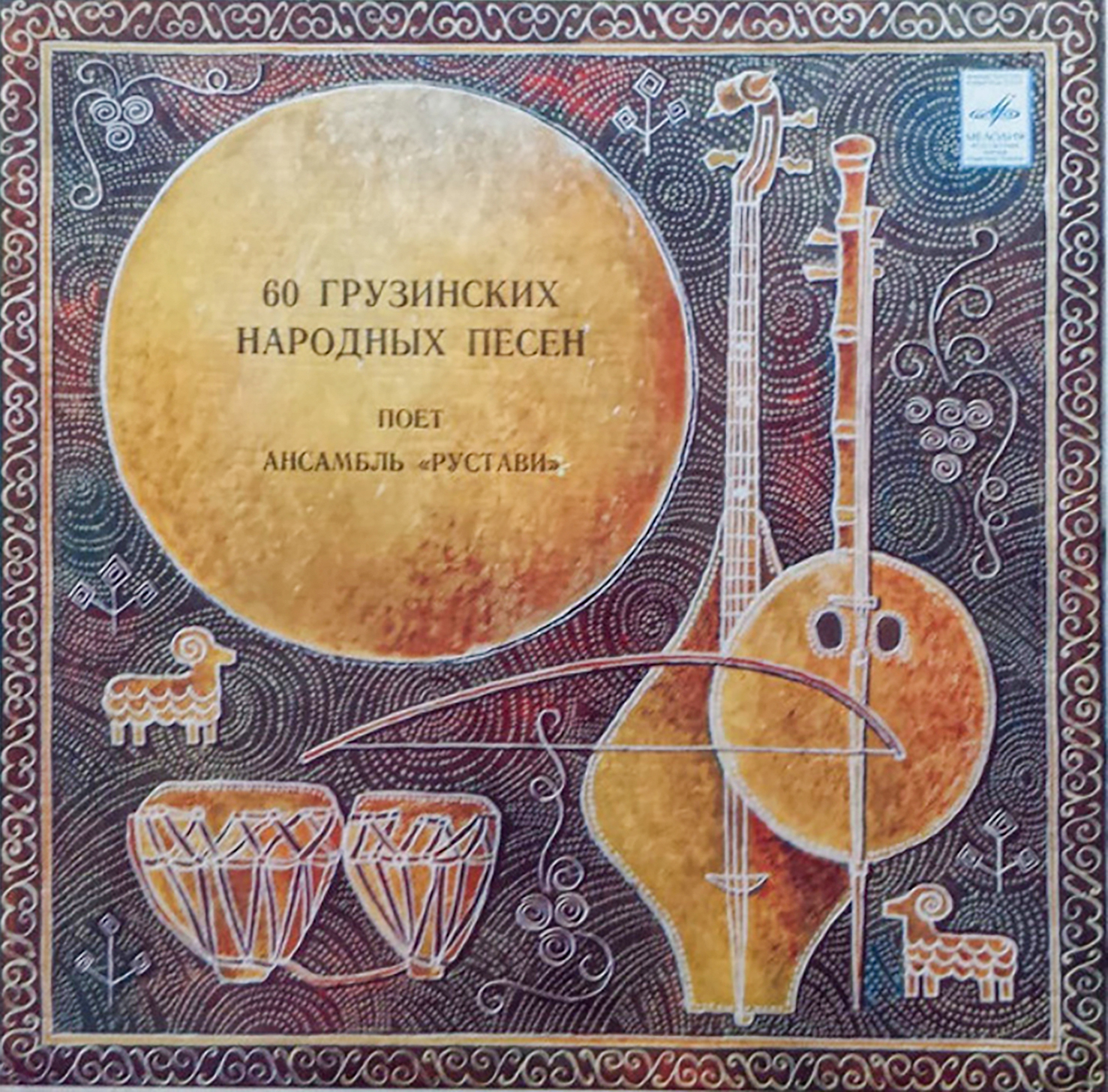

However, with regard to other hymns, censorship remained partially in place. An example of this is the vinyl record set 60 Georgian Folk Songs by the ensemble Rustavi, which included hymns alongside folk songs. However, in the annotations, all the hymns were listed without titles and were simply referred to as 'chorals.'[12] What caused this 'disguise' of the hymns, which persisted even until 1980? It seems that the relative leniency toward Georgian chant within Georgia did not extend throughout the Soviet Union, and thus, the aforementioned method of circumventing censorship was used for records printed in Moscow.

On the other hand, in 1970, the brilliant director Soso Chkhaidze, through the Georgian Telefilm company, made a documentary film titled Dzveli Kartuli Sagaloblebi (Old Georgian Chants). The film is entirely dedicated to showcasing the monuments of old Georgian architecture, churches, hymnographic manuscripts, frescoes, and enamel samples. The soundtrack includes fragments of ancient Georgian hymnographic texts[13] as well as chants performed by the ensemble Rustavi.[14] In this regard, Anzor Erkomashvili recalls: 'I first worked with Soso Chkhaidze on Old Georgian Chants...

We recorded the hymns on phonograph tapes, since at that time the Melodia company did not have a recording studio. The recordings were made in the large hall of the Conservatoire. During the day, noise would enter the hall, so recording began after 1 a.m. and often lasted until morning. A few months later, the film was ready, but the review commission refused to accept it, declaring it politically unacceptable. The Minister of Culture, Otar Takhtakishvili, Rezo Chkheidze (a film director), and Academician Vakhtang Beridze intervened. They liked the film very much and found a way to save it – as a film about rare Georgian monuments, it was acquired by the Institute of Art History and… was still placed on the shelf. Later, time did its work, and the film never stopped airing on television... it was even used to introduce Georgian culture abroad. [15]

This story clearly shows that in Soviet Georgia, state censorship of chant still existed during this period, but it no longer manifested with the same harshness.

Director — Soso Chkhaidze

From the second half of the 1980s, the situation began to change. A new wave of interest in Georgian chant emerged in society. During this period, a male student ensemble was formed at the Tbilisi Conservatoire, with the aim of reviving forgotten manuscripts and recordings of hymns. Starting in 1988, this ensemble began chanting at the ancient church of Anchiskhati in Tbilisi, marking the beginning of the process to restore ancient Georgian chant.

Anchiskhati choir. Left to right: Reso Kiknadze, Zaal Tsereteli, Guram Gagoshidze, David Zatiashvili, Temur Imnadze, Aleksandre Khakhishvili, Malkhaz Erkvanidze, David Shughliashvili

The ensemble, later named the Anchiskhati Choir, revived ancient tunes preserved in 19th-century notated transcriptions—melodies that no one in the country knew anymore, as there seemed to be no one left alive who had knowledge of them. The ensemble released vinyl records, compact discs, and notated collections of old traditional chants, greatly contributing to the growing popularity of Georgian chant, both within Georgia and abroad. It is no coincidence that this all took place during the period of Georgia’s restoration of independence. The history of the Anchiskhati Choir and its contribution to Georgian traditional chant deserves a separate, dedicated article.

[1] Tsintsadze, Kalistrate. 1994. The Kvashveti Church of St. George in Tbilisi. Tbilisi: Kandeli.

[2] These audio recordings are stored in the archive of the Folk Arts Laboratory at the Tbilisi State Conservatory. In 2004, these recordings were released in the form of a compact disc (with accompanying notated transcriptions) titled Eleven Pearls; See: Shughliashvili, Davit, ed. 2004. Eleven Pearls. Compact disc. Folk Arts Laboratory, Tbilisi State Conservatoire.

[3] We are referring to hymns performed by Samuel Chavleishvili, Samuel Chkikvishvili, and Besarion Intskirveli. See Erkomashvili, Anzor, and Vakhtang Rodonaia. 2006. Georgian Folk Songs: The First Audio Recordings, 1901–1914. Tbilisi: Kandeli.

[4] See National Archive of Georgia, Department of Phonodocuments, Reels ##668-671.

[5] The full version of this hymn can be found in "Eleven Pearls."

[6] Audio archive of the Folklore Laboratory of the Tbilisi State Conservatoire. 1965. "Audio Recording Tape 172, #18." Recorded in the village of Van-Zomleti, Lanchkhuti District, by Otar Chijavadze.

[7] National Archive of Georgia, Department of Phonodocuments.

[8] Tbilisi State Conservatoire Folklore Laboratory Audio Fund. 1966. Audio recordings, tapes ##174-189

[9] See the works of Pavle Ingorokva, Shalva Aslanishvili, Otar Chijavadze, Evsevi Chokhonelidze, Kakhi Rosebashvili, and other scholars.

[10] Rosebashvili, Kakhi. 1968. Georgian Chant (Imereti-Guria Style). Tbilisi: Georgian Department of the USSR Musical Fund.

[11] Georgia in Folk Songs: Anthology of Georgian Folk Songs. 1968. Tbilisi.

[12] Ensemble "Rustavi". 1980. 60 Georgian Folk Songs. Melodia, Moscow.

[13] The film featured fragments of hymnal texts by David the Builder, Demetre I, Mikheil Modrekili, and Ioane Minchkhi for the first time.

[14] The film includes the complete hymns: "Romelini K'erubimta" (“Cherubic Hymn"), "Jvars'a Shensa" ("Thy Cross"), "Shen Kh'ar Veneakhi" ("You Are the Vineyard"), the Gurian "Zari" (a funeral chant), "Mots'iquli Khristesgan Gamorcheulia" ("The Apostle Chosen by Christ"), and "Tsmidao Ghmerto" ("Holy God")

[15] Soso Chkhaidze. "Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia." Accessed December 23, 2024. https://ka.wikipedia.org/wiki/სოსო_ჩხაიძე.